Article Database

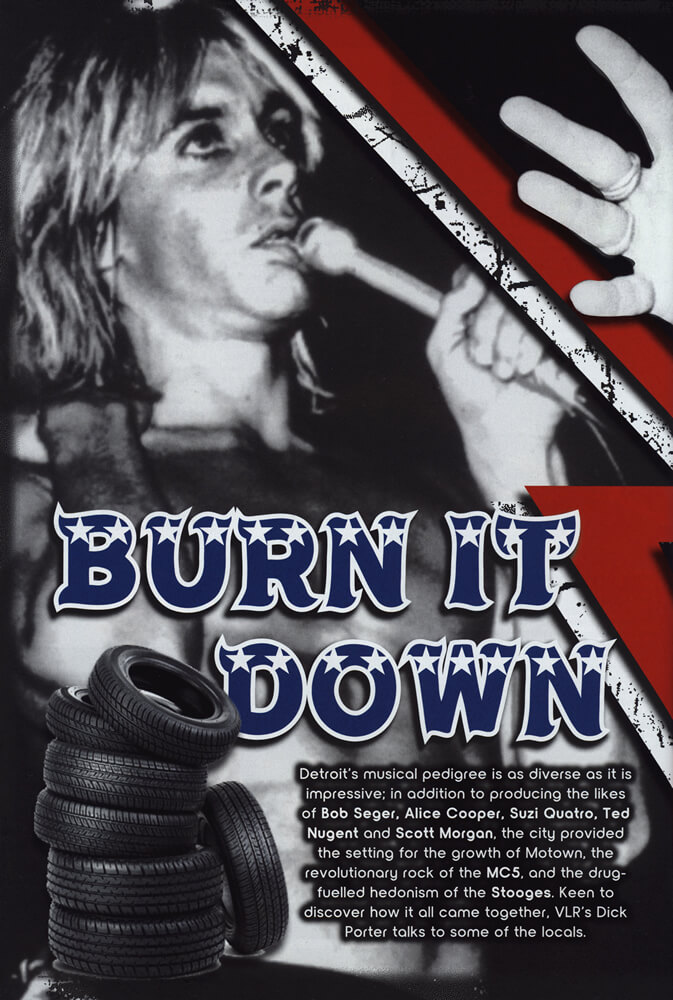

Burn It Down

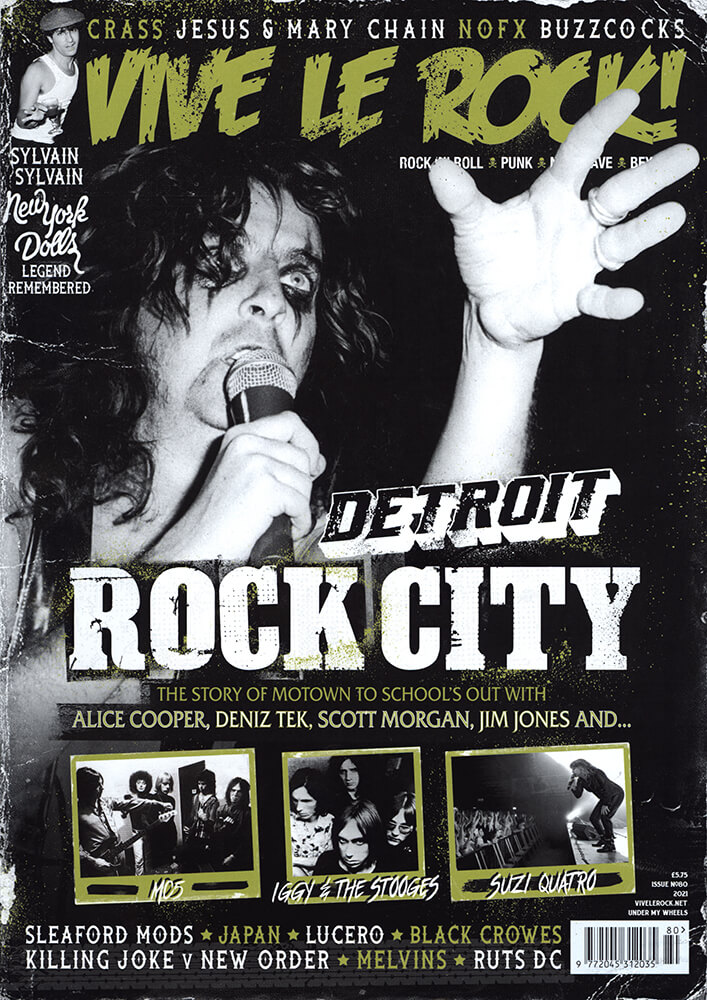

Detroit's musical pedigree is as diverse as it is impressive; in addition to producing the likes of Bob Seger, Alice Cooper, Suzi Quatro, Ted Nugent and Scott Morgan, the city provided the setting for the growth of Motown, the revolutionary rock of the MC5, and the drug-fuelled hedonism of the Stooges. Keen to discover how it all came together, VLR's Dick Porter talks to some of the locals.

IN terms of the historical dynamics of major American cities, Detroit is both typical and unique — As was the case in several other urban centres across the US, the development of industrial manufacturing enabled the city to grow rapidly during the first half of the 20th century, enabling a post war boom as consumer demand reached a peak during the 1950s, before undergoing an accelerating decline as the 1960s gave way to the '7Os. What makes it notable, are the singular social and racial dynamics that gave rise to a culture unlike that to be found anywhere else.

"Detroit was unique," explains MCS mainstay Wayne Kramer, "in that it was in the North, and it was the final destination of rural people, both black and white from the South — going back to the Civil War, the Underground Railroad; black people wanting to get up to the north. And Detroit was a huge manufacturing, industrial city. There was a lot of good union work, and I think that work is the glue that holds people together. Even though there were black neighbourhoods, Italian neighbourhoods, Polish neighbourhoods, and Mexican neighbourhoods, as a boy I could ride my bicycle through any of them and never be afraid."

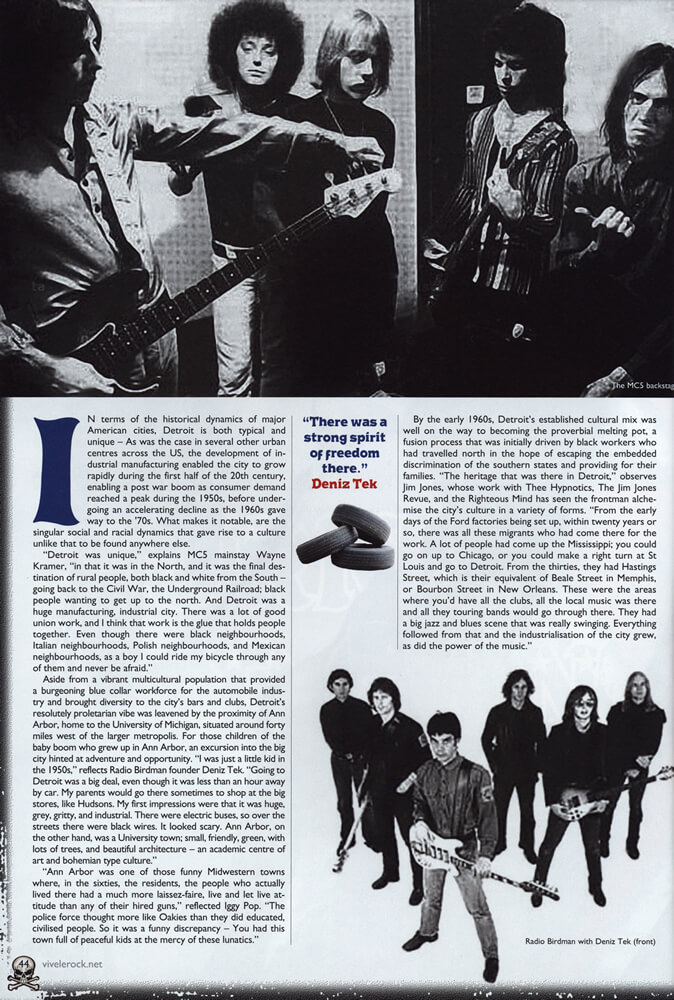

Aside from a vibrant multicultural population that provided a burgeoning blue collar workforce for the automobile industry and brought diversity to the city's bars and clubs, Detroit's resolutely proletarian vibe was leavened by the proximity of Ann Arbor, home to the University of Michigan, situated around forty miles west of the larger metropolis. For those children of the baby boom who grew up in Ann Arbor, an excursion into the big city hinted at adventure and opportunity. "I was just a little kid in the 1950s," reflects Radio Birdman founder Deniz Tek. "Going to Detroit was a big deal, even though it was less than an hour away by car. My parents would go there sometimes to shop at the big stores, like Hudsons. My first impressions were that it was huge, grey, gritty, and industrial. There were electric buses, so over the streets there were black wires. It looked scary. Ann Arbor, on the other hand, was a University town; small, friendly, green, with lots of trees, and beautiful architecture — an academic centre of art and bohemian type culture."

"Ann Arbor was one of those funny Midwestern towns where, in the sixties, the residents, the people who actually lived there had a much more laissez-faire, live and let live attitude than any of their hired guns," reflected Iggy Pop. "The police force thought more like Oakies than they did educated, civilised people. So it was a funny discrepancy — You had this town full of peaceful kids at the mercy of these lunatics."

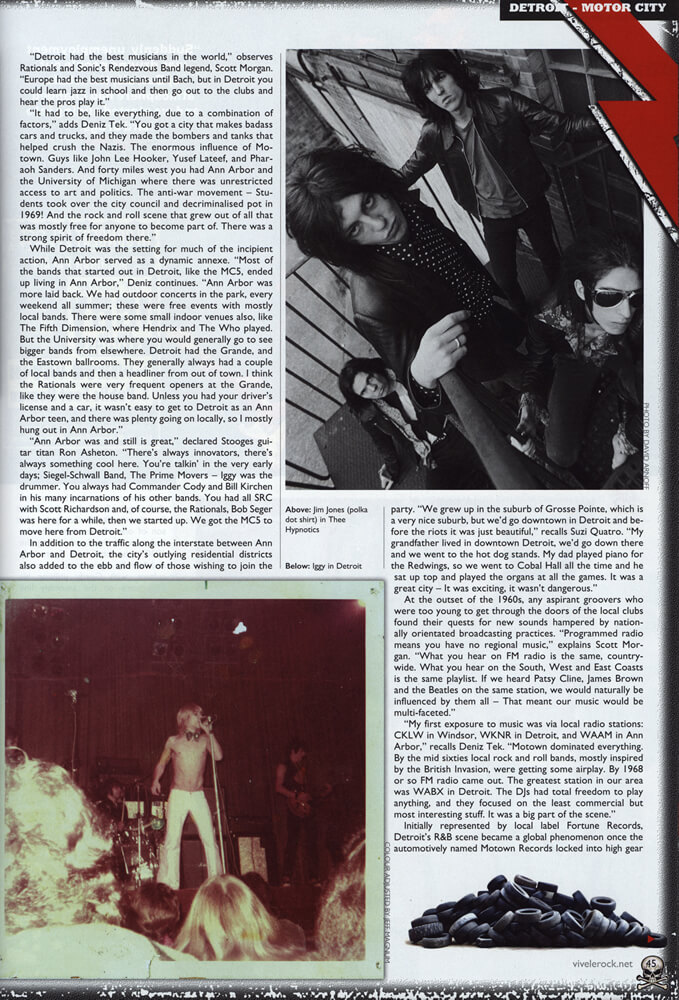

By the early 1960s, Detroit's established cultural mix was well on the way to becoming the proverbial melting pot, a fusion process that was initially driven by black workers who had travelled north in the hope of escaping the embedded discrimination of the southern states and providing for their families. "The heritage that was there in Detroit," observes Jim Jones, whose work with Thee Hypnotics, The Jim Jones Revue, and the Righteous Mind has seen the frontman alchemise the city's culture in a variety of forms. "From the early days of the Ford factories being set up, within twenty years or so, there was all these migrants who had come there for the work. A lot of people had come up the Mississippi; you could go on up to Chicago, or you could make a right turn at St Louis and go to Detroit. From the thirties, they had Hastings Street, which is their equivalent of Beale Street in Memphis, or Bourbon Street in New Orleans. These were the areas where you'd have all the clubs, all the local music was there and all they touring bands would go through there. They had a big jazz and blues scene that was really swinging. Everything followed from that and the industrialisation of the city grew, as did the power of the music."

"Detroit had the best musicians in the world," observes Rationals and Sonic's Rendezvous Band legend, Scott Morgan. "Europe had the best musicians until Bach, but in Detroit you could learn jazz in school and then go out to the clubs and hear the pros play it."

"It had to be, like everything, due to a combination of factors," adds Deniz Tek. "You got a city that makes badass cars and trucks, and they made the bombers and tanks that helped crush the Nazis. The enormous influence of Motown. Guys like John Lee Hooker, Yusef Lateef, and Pharaoh Sanders. And forty miles west you had Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan where there was unrestricted access to art and politics. The anti-war movement — Students took over the city council and decriminalised pot in 1969! And the rock and roll scene that grew out of all that was mostly free for anyone to become part of. There was a strong spirit of freedom there."

While Detroit was the setting for much of the incipient action, Ann Arbor served as a dynamic annexe. "Most of the bands that started out in Detroit, like the MCS, ended up living in Ann Arbor," Deniz continues. "Ann Arbor was more laid back. We had outdoor concerts in the park, every weekend all summer; these were free events with mostly local bands. There were some small indoor venues also, like The Fifth Dimension, where Hendrix and The Who played. But the University was where you would generally go to see bigger bands from elsewhere. Detroit had the Grande, and the Eastown ballrooms. They generally always had a couple of local bands and then a headliner from out of town. I think the Rationals were very frequent openers at the Grande, like they were the house band. Unless you had your driver's license and a car, it wasn't easy to get to Detroit as an Ann Arbor teen, and there was plenty going on locally, so I mostly hung out in Ann Arbor."

"Ann Arbor was and still is great," declared Stooges guitar titan Ron Asheton. "There's always innovators, there's always something cool here. You're talkin' in the very early days; Siegel-Schwall Band, The Prime Movers — Iggy was the drummer. You always had Commander Cody and Bill Kirchen in his many incarnations of his other bands. You had all SRC with Scott Richardson and, of course, the Rationals, Bob Seger was here for a while, then we started up. We got the MCS to move here from Detroit."

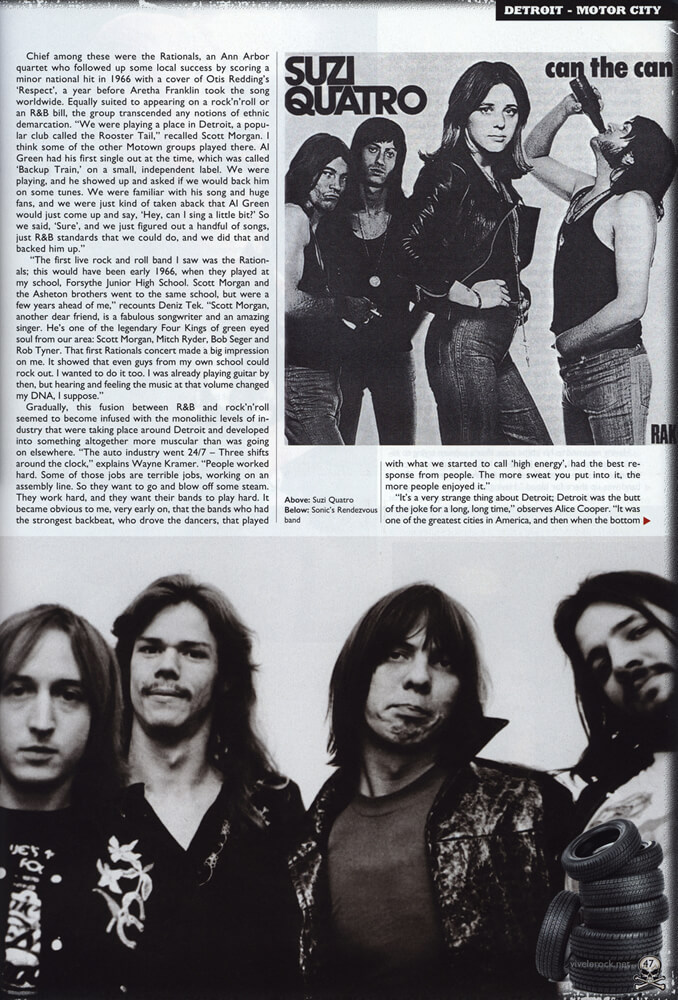

In addition to the traffic along the interstate between Ann Arbor and Detroit, the city's outlying residential districts also added to the ebb and flow of those wishing to join the party. "We grew up in the suburb of Grosse Pointe, which is a very nice suburb, but we'd go downtown in Detroit and before the riots it was just beautiful," recalls Suzi Quatro. "My grandfather lived in downtown Detroit, we'd go down there and we went to the hot dog stands. My dad played piano for the Redwings, so we went to Cobal Hall all the time and he sat up top and played the organs at all the games. It was a great city — It was exciting, it wasn't dangerous."

At the outset of the 1960s, any aspirant groovers who were too young to get through the doors of the local clubs found their quests for new sounds hampered by nationally orientated broadcasting practices. "Programmed radio means you have no regional music," explains Scott Morgan. "What you hear on FM radio is the same, countrywide. What you hear on the South, West and East Coasts is the same playlist. If we heard Patsy Cline, James Brown and the Beatles on the same station, we would naturally be influenced by them all — That meant our music would be multi-faceted."

"My first exposure to music was via local radio stations: CKLW in Windsor, WKNR in Detroit, and WAAM in Ann Arbor," recalls Deniz Tek. "Motown dominated everything. By the mid sixties local rock and roll bands, mostly inspired by the British Invasion, were getting some airplay. By 1968 or so FM radio came out. The greatest station in our area was WABX in Detroit. The DJs had total freedom to play anything, and they focused on the least commercial but most interesting stuff. It was a big part of the scene."

Initially represented by local label Fortune Records, Detroit's R&B scene became a global phenomenon once the automotively named Motown Records locked into high gear during the first half of the 1960s. Founded by Berry Gordy Jr., the son of one of the multitude who had escaped the South during the 1920's, the label both figuratively and literally represented the city's culture, with Gordy utilising his experience on the assembly line to establish production methods that mirrored those in the nearby factories. "Berry Gordy tried to replicate the way in which the motor plants worked," explains Jim Jones. "This is where we build the chassis, this is where we put the paintwork on; and he had the same thing with his artists — This is where we write the songs, this is where they're recorded, this is where we show them the dance steps, this is where they learn how to speak in interviews, and it was churned out — They called it the 'Hit Factory'."

Aside from catapulting the likes of Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross, Smokey Robinson, The Four Tops, and Martha Reeves to international stardom and playing a significant role in enabling increased racial integration among America's youth, the influence of Motown seeped into the very substance of Detroit where it combined with the impact being made by imported British pop, to inspire a generation of young groups who equally assimilated music that had previously been divided into 'black' and 'white' categories, and duly marketed separately.

Chief among these were the Rationals, an Ann Arbor quartet who followed up some local success by scoring a minor national hit in 1966 with a cover of Otis Redding's 'Respect', a year before Aretha Franklin took the song worldwide. Equally suited to appearing on a rock'n'roll or an R&B bill, the group transcended any notions of ethnic demarcation. "We were playing a place in Detroit, a popular club called the Rooster Tail," recalled Scott Morgan. I think some of the other Motown groups played there. Al Green had his first single out at the time, which was called 'Backup Train,' on a small, independent label. We were playing, and he showed up and asked if we would back him on some tunes. We were familiar with his song and huge fans, and we were just kind of taken aback that Al Green would just come up and say, 'Hey, can I sing a little bit?' So we said, 'Sure', and we just figured out a handful of songs, just R&B standards that we could do, and we did that and backed him up."

"The first live rock and roll band I saw was the Rationals; this would have been early 1966, when they played at my school, Forsythe Junior High School. Scott Morgan and the Asheton brothers went to the same school, but were a few years ahead of me," recounts Deniz Tek. "Scott Morgan, another dear friend, is a fabulous songwriter and an amazing singer. He's one of the legendary Four Kings of green eyed soul from our area: Scott Morgan, Mitch Ryder, Bob Seger and Rob Tyner. That first Rationals concert made a big impression on me. It showed that even guys from my own school could rock out. I wanted to do it too. I was already playing guitar by then, but hearing and feeling the music at that volume changed my DNA. I suppose."

Gradually, this fusion between R&B and rock'n'roll seemed to become infused with the monolithic levels of industry that were taking place around Detroit and developed into something altogether more muscular than was going on elsewhere. 'The auto industry went 24/7 — Three shifts around the clock," explains Wayne Kramer. "People worked hard. Some of those jobs are terrible jobs, working on an assembly line. So they want to go and blow off some steam. They work hard, and they want their bands to play hard. It became obvious to me, very early on, that the bands who had the strongest backbeat, who drove the dancers, that played with what we started to call 'high energy', had the best response from people. The more sweat you put into it, the more people enjoyed it."

"It's a very strange thing about Detroit; Detroit was the butt of the joke for a long, long time," observes Alice Cooper. "It was one of the greatest cities in America, and then when the bottom dropped out of the car business there was a lot of drugs and downtown became the murder capital because of the drugs and it was the punchline for almost every joke — Cleveland or Detroit. The funny thing is that anybody from Detroit is proud to be from Detroit. It's the hard rock capital of the United States. If you ask any band what is the best city in America to play if you're a hard rock band and they'll tell you; Detroit. Because that audience; they do not like soft rock. Mom and Dad work on the assembly line and it's not very sophisticated — These people who grew up there were born into hard rock; Iggy and the Stooges, MC5, Alice Cooper, Ted Nugent, Bob Seger, Suzi Quatro — All the bands that came out of there were hard rock bands, really hard rock bands, and no band ever came out of Detroit that was like 'Seals and Crofts' or anything."

In Detroit, rock'n'roll was not an art form in the way that it was in bohemian New York or laidback Los Angeles; it was a release, fuelled by passion and infused with a singularly combative attitude. "What happened was that we were in Los Angeles, and we were playing gigs and people felt that we were kind of a novelty. In LA and New York, their attitude is, 'OK, I'm hip — Show me', that kind of thing," continues Alice. "So, the Doors were great; they were one of the best live bands that I ever heard and they didn't bend to anybody, and they were sexy, and they had this LA sound. San Francisco had the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, and New York had the Young Rascals. Detroit though, was the Midwest and there were no frills — You knew it was gonna be hard rock, and you knew it was gonna be loud and the audience was going to be rowdy — It was almost like that the first time that I played Glasgow. They loved Slade over there, they loved T Rex, they loved Bowie, they loved all the bands that would come over — The more outrageous the better as long as they delivered musically. If they came over and was freaky but didn't do anything, nobody cared. But if they came over like Arthur Brown did, and got up there and nailed it, they loved it. They would rather see that than somebody with an acoustic guitar."

Having returned to his home state after a sojourn trying to establish his band in LA, Alice found the MC5 ruling the local roost. "Detroit was the antithesis of Los Angeles," he noted. "Every band was up there for blood." Having started out covering pop hits, the MC5 had developed an improvisational approach that drew upon jazz influences that, in part, had been introduced to the group by their manager John Sinclair, who would also attempt to similarly radicalise the band's political outlook. Live, the quintet of frontman Rob Tyner, guitarists Wayne Kramer and Fred 'Sonic' Smith, and the powerhouse Michael Davis / Dennis Thompson rhythm section were a force of nature, using excessive amplification to meld their extended freakouts into something resembling a sonic attack, while presenting the whole devastating package with the kind of stagecraft more commonly associated with a well drilled R&B outfit. "When I first saw them they were just a really fuckin' good big city covers band, and they covered the Stones, Hendrix, The Who, all that shit real well," recalled Iggy. "And then they knew a little Ray Charles and shit. As they developed, I thought there was an overlay of jazz, but a lot of the music values were very hard rock."

"The first time I saw the MC5 was a revelation," declares Deniz Tek. "It wasn't introspective, it was a show! In your face, with huge volume, great playing, and some loose choreography — kind of like the Motown Revue. They were putting out all this energy and the lines between the band and the audience sort of dissolved in one big exchange of power."

"Seeing the MCS live was great — That sticks out because they really were a great live act," recalls Suzi Quatro, whose group, the Pleasure Seekers also infused their girl group garage sound with elements of Motown-influenced R&B. "They were much better live than they ever were on record; they never could capture that, I don't know why. They were a great live rock'n'roll band, you couldn't get better."

"As the Stooges got together, the MCS were always playing also," recounted Ron Asheton. "So we got to do a bunch of shows together. I always admired them because I loved the big sound. They had the Marshall stacks. It was never like competition. We played with them a million times. In those days, bands rooted for the other guys where today, it's just like big corporations; 'Fuck them, they suck'. No one's really friendly or anything. Back then, everyone was really supportive of each other."

"You have to remember that Detroit is an industrial city, like Newcastle, and it's not very sophisticated, but they do understand one thing; they understand hard rock with attitude," observes Alice. "You have to bring it every night, and they can tell if you're not bringing it. That's why Suzi Quatro was great; she was in an all-girl band and I'll tell you what, those girls rocked every night. They got up there and killed it every night, and that's the attitude that you had to have when you were in Detroit. I think that goes back to meaning what you're saying, rather than just saying it — Meaning it, and making people believe it. They were very open to theatrics too; the MC5 was very much a showband, they were almost like a black revue, only they were white guys.

"I've known Wayne Kramer since 1968 in East Detroit," continues Cooper. "We used to play together at least three or four times a month in different shows. In 1970, it was a common show at the East Town Theater, which held about a thousand people; it would be the Stooges, the MC5, Alice Cooper and The Who. That's a pretty great rock'n'roll dungeon right there. The next week it would be Suzi Quatro, Alice Cooper, Bob Seger and Savoy Brown. Those big bands from England did not come in and play arenas, they came in and they played clubs, or they played theatres. We opened for the Yardbirds; we opened for all these bands that were our heroes back then. When I look back at those days, what great rock'n'roll nights they were. And that would just be one show; there were three or four other shows that night. So Detroit was just the heart and soul of hard rock."

Although the notion of a 'scene' is often an illusory method of lumping together a clutch of artists from a similar locale, the bands orbiting Detroit's clubs in the second half of the sixties shared influences and characteristics served to unify them as a uniquely dynamic generation of musicians, all in the same place at the same time, and regularly on the same bills. "Other great bands that I can remember being impacted by were the Amboy Dukes, the Frost, SRC, and The Up," recalls Deniz Tek. "Alice Cooper was another one that was into bizarre showmanship. I was fascinated by Carnal Kitchen, who were doing a sort of free jazz — I couldn't understand any of it but loved the freedom and wildness. I can say the same about The Stooges — probably worth a whole article, they were so different. No actual songs, in the early days, just intense jams they called 'energy freakouts'. Maybe you can imagine what it was like to be an impressionable, curious teenager in those circumstances. I just soaked it all up."

"I remember playing a gig with Bob Seger, I must have been about fifteen, and he came on before us and sat down at a piano and sang his own songs, and I thought that was unusual, but boy was he talented," Suzi recounts. "He wasn't famous yet. I saw Iggy when he was still a drummer, and Ted Nugent — We did lots of gigs with him and Alice &mdsah; My band used to rehearse in his garage, because they were just outside of the limits and they had a barn where we used to go over to rehearse and we were all friends."

"At that time none of us knew who was going to make it," reflects Alice. "It was like that in LA too — Back in 1968, we played the Whisky a Go Go with some band called Led Zeppelin and nobody had heard of either one of us. The very next night we played some place called the Cheetah Club and they said, 'Who's playing with you?' And I said, 'I dunno — Some guy named Pink Floyd'. Back then nobody knew who was going to make it, and it ended up that most of us did: Iggy and the Stooges became a world phenomenon. They didn't sell a lot of records, but they were just who they were — They were really something. MC5 had this whole thing where they were very political hard rock, 'Kick Out The Jams' and that, and Alice Cooper was this weird, dark vaudeville, but still hard rock. We were the first ones who had a record that actually took off; 'I'm Eighteen' took off out of CKLW in Windsor, Ontario. It was the biggest station in the Midwest, even though it was in Canada. So when 'I'm Eighteen' broke on that station, we were suddenly a national act, because with one record you could go on tour nationally then. So I give all the credit in the world to Rosalie Trombley, who was the programme director there at CKLW. It was one of those records that didn't really fit in the Top Forty, but people loved it."

Hot on the heels of the MC5 came the (initially 'Psychedelic') Stooges. Younger and even wilder than the Five, the quartet of Iggy Pop, Ron and Scott Asheton, and bassist Dave Alexander had a similar penchant for whipping up avant garde sonic freakouts. However, while the MC5 were channelling Sun Ra or Pharaoh Saunders, the Stooges kicked up a din out of necessity. "Usually we got up there and jammed one riff, and built into an energy freak out, until finally we'd broken a guitar, or one of my hands would be twice as big as the other and my guitar would be covered in blood," recalled Ron. "We were lucky enough to have the Grande in full swing, and that was a good venue for us. There'd be sympathetic people there. The people that came there were supposedly, most of them, hip, so that's where the old Psychedelic Stooges really learned how to play and came forward, playing the Grande Ballroom. Thank god for the Grande Ballroom, or we wouldn't have worked."

"The Stooges had their own theatre; Iggy was his own theatre, and then Alice Cooper was this other kind of theatre, but all three bands were in your face and I think that was what they wanted. They wanted you to be in their faces," muses Alice. "The Detroit bands were all like brothers — We partied every weekend, everybody knew everybody. After every show, we'd either go to the Stooges house, or the MC5's house, or the Alice Cooper house and there would be a party. I can't think of anyplace else that did that; Los Angeles didn't do that, New York didn't do that. In Detroit it was much more of a brotherhood — And here's the weird part: We'd be up on stage at the Grande Ballroom, and you're playing and just killing it, and it's wild and sweaty, and you look down and there's Smokey Robinson, or you look over to the left and there's one of the Supremes, or two of the guys from the Temptations, because the Motown guys really liked hard rock. It was one of those cities where Motown and hard rock really got along together. And if those guys were playing anywhere, we would all go down. There was no racial thing going on at all; if you had long hair and you had a band, you were not the enemy. Even during the riots, you were not the enemy."

"There's a place where they merge; if the rock'n'roll is psychotic enough, and if the black music is driving enough, they kind of cross," observes Jim Jones. "The great music that's come out of Detroit has had the best of both cultures."

"We played gigs with all the bands that were coming up; we worked with Bob Seger, the MC5, Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop — I can go on and on," adds Suzi. "I also had a year dancing on a local television show, in which I was one of the regular people in the audience dancing and I saw all the acts two inches away from me. I could learn the Temptations' routines before they became public, that was great. We all grew up together in that scene, we all took a lot of influence from Motown — In the moves, in the bass and drum sound, and then everybody puts it through themselves in their own way."

Although the younger generation were overcoming America's racial divide, the Detroit riots of July 1967 demonstrated that systemic racism was still very much alive and kicking. Housing was still largely segregated upon racial and economic lines, with any black families moving into white neighbourhoods finding that they were met by hostility and threats. Although the city administration had invested in inner city renewal programs during the early part of the decade, and pay for unskilled black workers was higher than elsewhere in the country, an overwhelmingly white police force proved to be an oppressive presence, with some officers using their positions to enable their personal prejudices. "I've been all over the world, and perhaps excluding Russia, I've never seen fascism more in force than in the Detroit area," declared Iggy.

The MC5 reacted to this by adopting an ideology in opposition to racism, and state oppression and exploitation that subsequently served to undermine their progress as a rock'n'roll band. We lived in a highly charged, polarised atmosphere — the war in Vietnam and military conscription. Every young man had skin in the game; we all had a dog in the fight, it affected everyone. So, as a band, we were just part of a larger sensitivity," explained Wayne Kramer. "It was a generational divide between my generation and my parents' generation — We were all in agreement that the grown-ups had blown it, and we had a better idea." Despite this generation gap, Wayne credits his mother for encouraging his enlightened perspective. "She felt like people are people; and if someone's a different colour or speaks a different language, you're every bit as good as they are, they're every bit as good as you. I wasn't raised with racist ideas or prejudicial ideas. She instilled in me what later became a political consciousness."

The riots marked the onset of a turning point for Detroit's rock'n'roll subculture; the MC5 became increasingly mired in controversy, the Stooges began the long march toward unheralded levels of hedonistic excess, and the likes of Alice Cooper, Ted Nugent, Bob Seger and Suzi Quatro dispersed to find wider success, either at home or abroad. "It got dangerous, then everything kind of went down," recalls Suzi. "It was scary for a while."

As the oil crisis of the early 1970s squeezed the profit margins of car manufacturers, factories were closed and thousands of workers laid off. This impacted on Detroit's downtown, which in turn suffered on account of the dramatically reduced levels of disposable local income, causing bars, clubs and restaurants to close. "They all left; they closed the factories down, they went places where they could build cars with no unions. So you ended up with a city with a bunch of leftover workers and no jobs," explains Wayne. "Suddenly, unemployment was driving people out of Detroit, the whole atmosphere had changed and we started sliding into hard drugs," Iggy recounted.

Those who departed often found watered down echoes of their hometown that compared unfavourably with the unique attitude and energy of Detroit's golden age. "I went to London in 1971," recalls Deniz Tek. "I went to the Marquee, because I knew that the Stones and the Who had played there. There was a band onstage that I had never heard of — The Pink Fairies. They were ripping it up, and I felt right at home. I remember thinking, 'Wow, these guys could give our locals a run for their money!' But after that exceptional case I began to realise that the scene and the music coming out of my home was different."

"It's an edgy, energetic feeling in Detroit that never leaves you," Suzi declares. "It's in your DNA and it never goes. I don't know what it is, but you feel it and it's electric. And total attitude — Attitude with a capital 'A'. I have always been very balanced; I take what I need out of that environment and I lead a balanced life. I'm not a sex, drugs and rock'n'roll girl, I'm pretty square, but I save all my wildness for the stage. But that doesn't stop me from wallowing in it, and seeing it and feeling it, and being able to write about it. I'm a Detroit girl in my heart and soul, and that will never leave me."

"The thing is, I don't see it as singular," continues Deniz. "For us, it was multifaceted. All those bands were not the same — the genres being presented were quite different, but the underlying current was probably attitudinal. The attitude generally was going for the throat and taking no prisoners, freedom of expression, passionate dedication, and the use of energy. Of course, that attitude thing was adopted later by many in the punk movement."

During the 1970s and 80s, the reverberations of what had gone down in Detroit and Ann Arbor during the 1960s resonated with successive new generations of rockers. "I remember the first time I heard the Stooges and the first time I heard the MC5, they were both moments when you said, 'What's this!?!' Suddenly the whole world moved and this was the centre of the universe. Everything falls into place, and it ticks all the boxes. I guess I would have been about fifteen or sixteen years old," recalls Jim Jones. "It went in there and quietly rearranged everything in my brain."

"My band, Thee Hypnotics, we really felt quite out on a limb, but kind of didn't give a fuck because we loved that sound so much," adds Jim. "At the time they tried to group us in with the grebo scene and the psychedelic scene, and various different things. Really, all it was, was that Detroit rock'n'roll sound was the main thing that we cared about and no one else was really doing it. People like Stiv Bators and Dave and Rat from The Damned all took us under their wing, and I think it's because they heard that in what we were doing. At the end of the day, we're talking about the Stooges and the MC5, but everything around it is important, and there's a ton of cool Detroit stuff — John Lee Hooker, Andre Williams, Motown of course, the early stuff that Bob Seger was doing, but the meat and potatoes of everything is the Stooges and the MC5. One of the things that really stuck out about that sound was that it was Motor City Rock'n'Roll, and it really did sound like an engine. If you listen to certain songs like 'Not Right' or 'Kick Out The Jams', the chord changes sound like a gear change on a hot rod. The way they played the music had the swing of the rock'n'roll to it, but it had that extra drive that really did sound like a muscle car being put through its paces. It had that car chase thrill about them in the way that the music was played."

Despite being left with an inner city that could reasonably be described as 'desolate', Detroit's musical subcultures rose again during the 1980s and 90s; first via the birth of techno, then through successive waves of garage bands and rap acts. "There's a very strange thing about Detroit," muses Alice. "There was only three white rappers that had any kind of street credibility — Eminem, Kid Rock, and the Insane Clown Posse. All white guys from Detroit, which is really weird. If they was from Nashville, people would have said, 'Nah, I don't care', but since they were from Detroit they had the authority to be white rappers — There was no real colour line there, black and white didn't matter. Jack White is from Detroit and he still defies every common rule of recording; his stuff is so inventive."

"Detroit is a very progressive town, but all anyone hears about is the negative shit. What nobody talks about is the spiritual energy of Detroit that encourages original work," observes MC5 bassist Michael Davis. "You don't keep Detroit down for long, it comes back," declares Suzi. "It was empty; I had my sixtieth birthday party there, and my husband had never been and he said that it looked like Hamburg after the war. I had my sixty-fifth birthday there too, and now they are restoring the city building by building, and it's starting to look beautiful again, and the people are starting to come back downtown again."

As Detroit regenerates, any developing subculture will represent a new point upon a uniquely dynamic social trajectory. "You'd go to other cities and you'd hear different things, or maybe there'd be something on a record — This is from a band out of Philly or whatever, and I always knew that Detroit had its own thing. It's that combination of the white and black together; there's the white rock and Motown and everything they did, and it just was perfect. I don't think there's a better music city in the world."

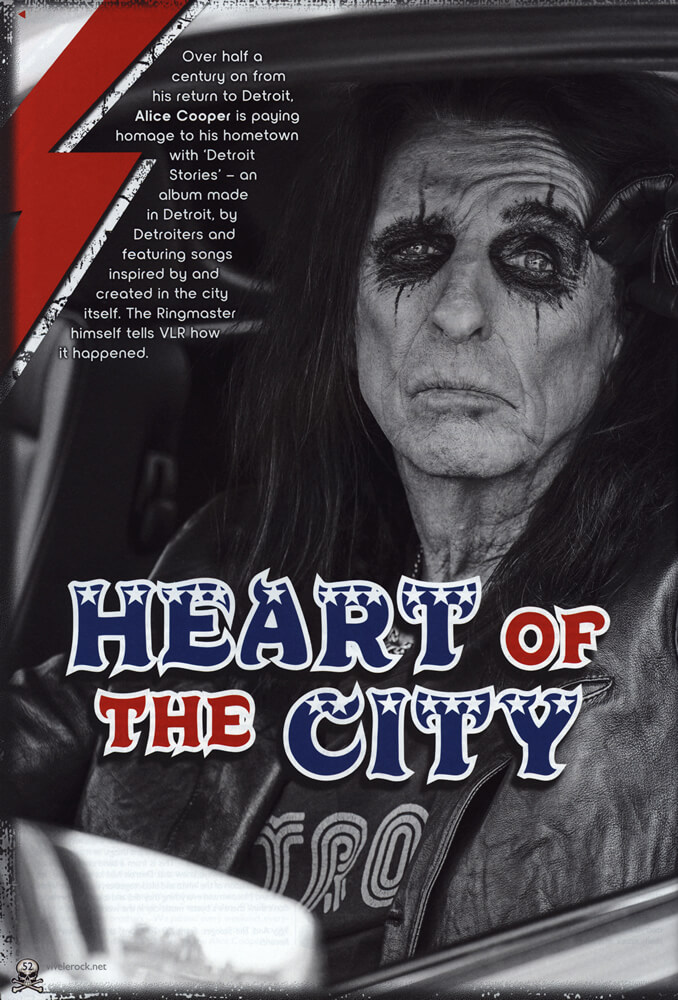

Heart of the City

Over half a century from his return, Alice Cooper is paying homage to his hometown with 'Detroit Stories' — an album made in Detroit, by Detroiters and featuring songs inspired by and created in the city itself. The Ringmaster himself tell VLR how it happened.

LIKE the rest of us, Alice Cooper is navigating his way through uncertain times. Having seen most things in his 73 years, he admits finding having inactivity suddenly forced upon him something of a shock to the system. "The weird thing for me is that I've never had ten months off," he declares. "We were in Berlin, and after the show they said, 'Okay, you've got twenty-four hours to get out of Germany because we're locking the whole country down', so we got back to the States as best we could. I figured that it would be a month, maybe two at most, and here we are ten months later and we're probably not going to be going out until May. But it's like anything else; we're humans, we're adaptable mdash; We have a vaccine and I think things will be back to normal after that."

In the meantime, like many other musicians, Alice found his focus shifting inexorably toward what could be achieved in the studio rather than on the road. "Bob [Ezrin, producer] and I had done all kinds of storylines, 'Paranormal' had done really well, and it was a story about twelve paranormal characters. In this case, Bob came to me with it; he said, 'What do you think about doing an album about Detroit?' So I said, 'We could do that if we do it in Detroit and use nothing but Detroit players and record it and write it there'. We saw a bunch of young punk bands there, we did our research and looked into bands from the eighties and nineties that never made it out of Detroit but every once in a while they'd have a song that made you go, 'Oh yeah, let's do that!' You'd call up this little band that's probably now broken up and say, 'Hey we're doing one of your songs'. And they'd say 'What!?!'

"I wanted the flavour of Detroit, and when you're using Detroit players — This is an odd thing; I don't know if it's like this with anybody else — Detroit guitarists, bassists, any instrument, have a certain amount of raw talent in their playing. I'm working with Johnny Bee, who was Mitch Ryder's drummer, and I'm working with Wayne Kramer from the MCS — All the guys that we used, when they would start playing a normal rock'n'roll song, you would go 'Oh man, this is great!' and then you would notice that there's a certain amount of R&B there that's just in the DNA. I think it's just there in the way that those guys play it, and so I said, 'Leave it in — I want that. If that's the flavour of Detroit, I want it in.' But we're a very guitar driven rock'n'roll band; we don't slow up for anybody on this album.

"I thought about characters that I would have known in Detroit. There's a song called 'Hail Mary', which is three old drunk guys sitting in an alley, they can't wait for this secretary to walk by every day, and her name is 'Mary' and they go 'Hail Mary, full of grace...' Every single song has got characters that you would meet in Detroit. I kind of generalised some of them; I write songs as stories, I don't really write them to be metaphors, or anything like that. I tried to write stories the way Chuck Berry did, and so when you get a song, you're getting a song about that specific character. I just remembered my uncles and aunts, my uncles' friends, and I kind of injected them into a lot of these songs. When I was a kid in Detroit, all my uncles were all Damon Runyon characters — They were all like Uncle Jockle, he was a prize-fighter, and he played left-handed guitar, and he owned a pool hall, maybe the most illegal pool hall in town. My Uncle Lefty was a total womaniser, he was a suave guy. Ratsy Bowers was their best friend.... Ratsy Bowers! He was another character. So I kinda grew up watching the fights with these guys on a black and white TV, in a smoke-filled room, and those things stay with you.

"I've got this album coming out, and I've already started working on the next one. I never even knew what Zoom was until I ended up being on it three times a day."

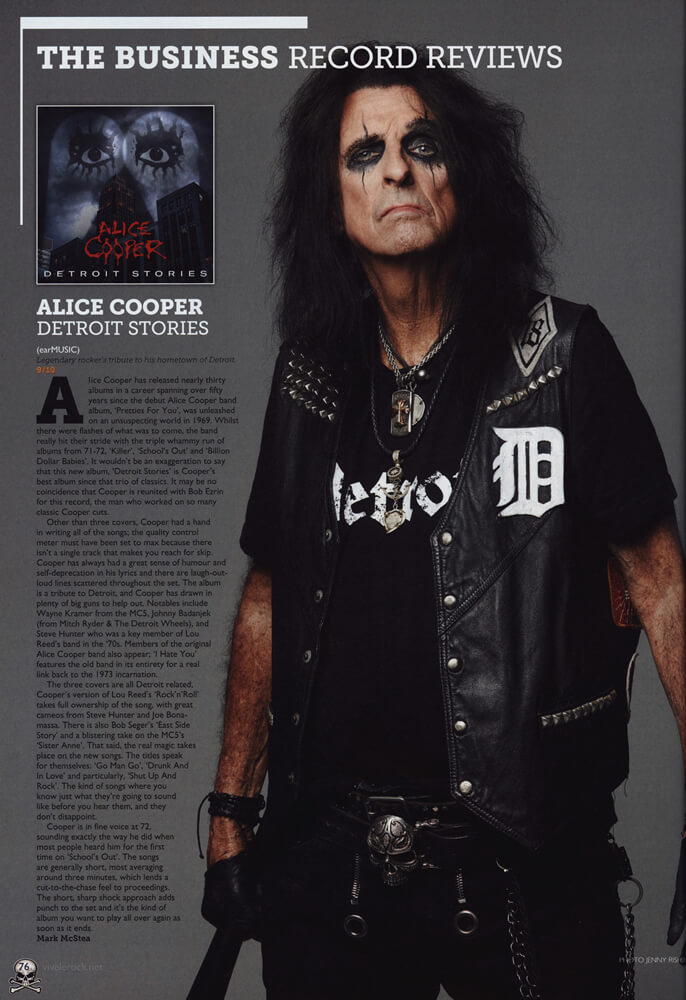

Alice Cooper - Detroit Stories

(earMusic)

Legendary rocker's tribute to his hometown of Detroit

9/10

Alice Cooper has released nearly thirty albums in a career spanning over fifty years since the debut Allee Cooper band album, 'Pretties For You', was unleashed on an unsuspecting work in 1969. Whilst there were flashes of what was to come, the band really hit their stride with the triple whammy run of albums from 71-72. 'Killer', 'School's Out' and 'Billion Dollar Babies'. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that this new album, 'Detroit Stories' is Cooper's best album since that trio of classics. It may be no coincidence that Cooper is reunited with Bob Ezrin for this record, the man who worked on so many classic Cooper cuts.

Other than three covers, Cooper had a hand in writing all of the songs; the quality control meter must have been set to max because there isn't a single track that makes you reach for skip. Cooper has always had a great sense of humour and self-deprecation in his lyrics and there are laugh-outloud lines scattered throughout the set. The album is a tribute to Detroit, and Cooper has drawn in plenty of big guns to help out. Notables include Wayne Kramer from the MC5, Johnny Badanjek (from Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels), and Steve Hunter who was a key member of Lou Reed's band in the '70s. Members of the original Alice Cooper band also appear; 'I Hate You' features the old band in its entirety for a real link back to the 1973 incarnation.

The three covers are all Detroit related, Cooper's version of Lou Reed"s "Rock'n'Roll" takes full ownership of the song, with great cameos from Steve Hunter and Joe Bonamassa. There is also Bob Seger's 'East Side Story' and a blistering take on the MC5's 'Sister Anne'. That said, the real magic takes place on the new songs. The tides speak for themselves: 'Go Man Go', 'Drunk And In Love' and particularly, 'Shut Up And Rock'. The kind of songs where you know just what they're going to sound like before you hear them, and they don't disappoint.

Cooper is in fine voice at 72, sounding exactly the way he did when most people heard him for the first time on 'School's Out'. The songs are generally short, most averaging around three minutes, which lends a cut-to-the-chase feel to proceedings. The short. sharp shock approach adds punch to the set and it's the kind of album you want to play all over again as soon as it ends.

Mark McStea