Article Database

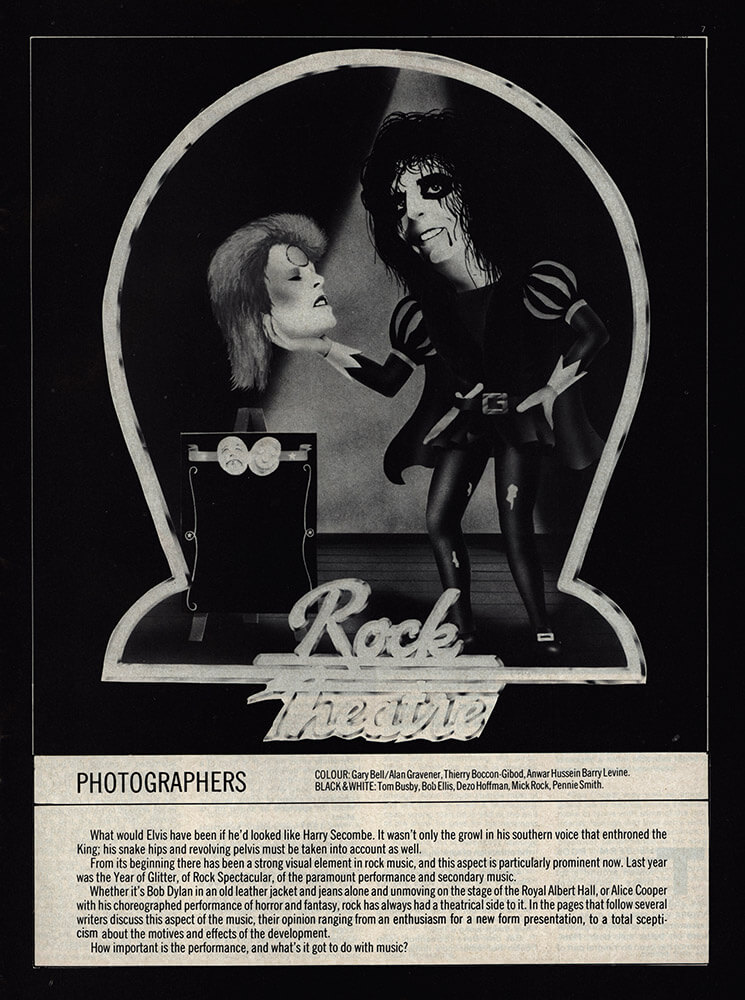

Rock Theatre

What would Elvis have been if he'd looked like Harry Secombe. It wasn't only the growl in his southern voice that enthroned the King; his snake hips and revolving pelvis must be taken into account as well.

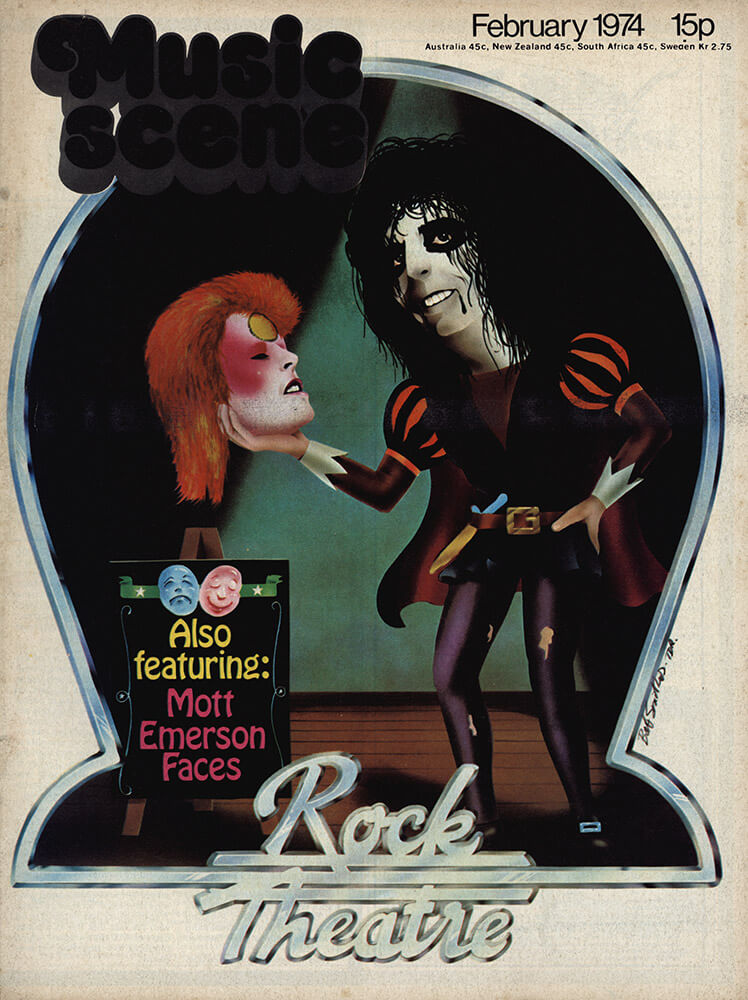

From its beginning there has been a strong visual element in rock music, and this aspect is particularly prominent now. Last year was the Year of Glitter, of Rock Spectacular, of the paramount performance and secondary music.

Whether it's Bob Dylan in an old leather jacket and jeans alone and unmoving on the stage of the Royal Albert Hall, or Alice Cooper with his choreographed performance of horror and fantasy, rock has always had a theatrical side to it. In the pages that follow several writers discuss this aspect of the music, their opinion ranging from an enthusiasm for a new form presentation, to a total scepticism about the motives and effects of the development.

How important is the performance, and what's it got to do with music?

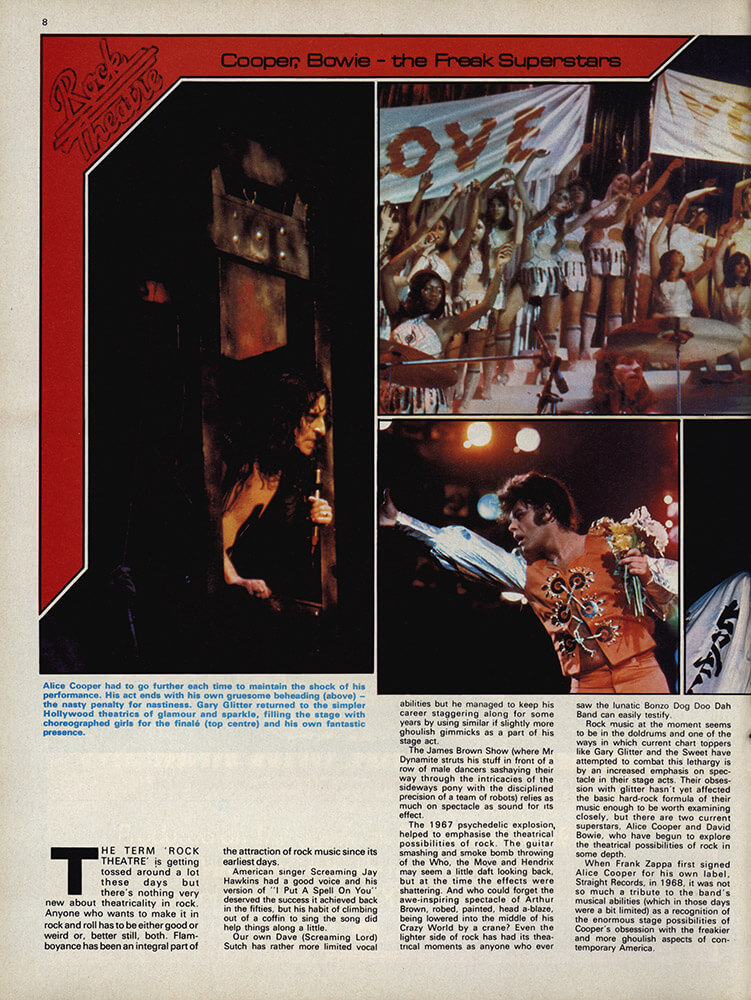

Cooper, Bowie - the Freak Superstars

THE TERM 'ROCK THEATRE' IS getting tossed around a lot these days but there's nothing very new about theatricality in rock. Anyone who wants to make it in rock and roll has to be either good or weird or, better still, both. Flamboyance has been an integral part of the attraction of rock music since its earliest days.

American singer Screaming Jay Hawkins had a good voice and his version of "I Put A Spell On You" deserved the success it achieved back in the fifties, but his habit of climbing out of a coffin to sing the song did help things along a little.

Our own Dave (Screaming Lord) Sutch has rather more limited vocal abilities but he managed to keep his career staggering along for some years by using similar if slightly more ghoulish gimmicks as a part of his stage act.

The James Brown Show (where Mr Dynamite struts his stuff in front of a row of male dancers sashaying their way through the intricacies of the sideways pony with the disciplined precision of a team of robots) relies as much on spectacle as sound for its effect.

The 1967 psychedelic explosion, helped to emphasise the theatrical possibilities of rock. The guitar smashing and smoke bomb throwing of the Who, the Move and Hendrix may seem a little daft looking back, but at the time the effects were shattering. And who could forget the awe-inspiring spectacle of Arthur Brown, robed, painted, head a-blaze, being lowered into the middle of his Crazy World by a crane? Even the lighter side of rock has had its theatrical moments as anyone who ever saw the lunatic Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band can easily testify.

Rock music at the moment seems to be in the doldrums and one of the ways in which current chart toppers like Gary Glitter and the Sweet have attempted to combat this lethargy is by an increased emphasis on spectacle in their stage acts. Their obsession with glitter hasn't yet affected the basic hard-rock formula of their music enough to be worth examining closely, but there are two current superstars, Alice Cooper and David Bowie, who have begun to explore the theatrical possibilities of rock in some depth.

When Frank Zappa first signed Alice Cooper for his own label, Straight Records, in 1968, it was not so much a tribute to the band's musical abilities (which in those days were a bit limited) as a recognition of the enormous stage possibilities of Cooper's obsession with the freakier and more ghoulish aspects of contemporary America.

By the time the band moved to Warner Bros. to cut their third album, "Love It To Death", in 1971, their music had improved out of all recognition, but the change in the music was at least partly the result of Cooper's development of his own bizarre notions of stage performance.

While the Beatles, with their Sergeant Pepper LP, were the first rock band to produce a 'concept album' by its themes, Alice Cooper was the first rock musician to explore the possibilities of albums that were designed as accompaniments to planned, tightly-structured theatrical performances.

Alice Cooper's London debut at the Rainbow in November 1971 was a revelation to the British audience. Arthur Brown, who was number two on the bill, had already got as far as ritual on-stage crucifixion but his act lacked conviction. The contrast between Brown's toy posturing and Alice Cooper's bizarre and nihilistic trip to the centre of the demonic void was staggering.

The act that Cooper was performing at that time was based directly on the "Love It To Death" album and the whole stock of ghoulish effects that Cooper was then using (boa constrictor, hammer, sword, straight jacket, culminating in his ritual execution in an electric chair) enabled him to create a characteristically macabre stage act that was totally convincing.

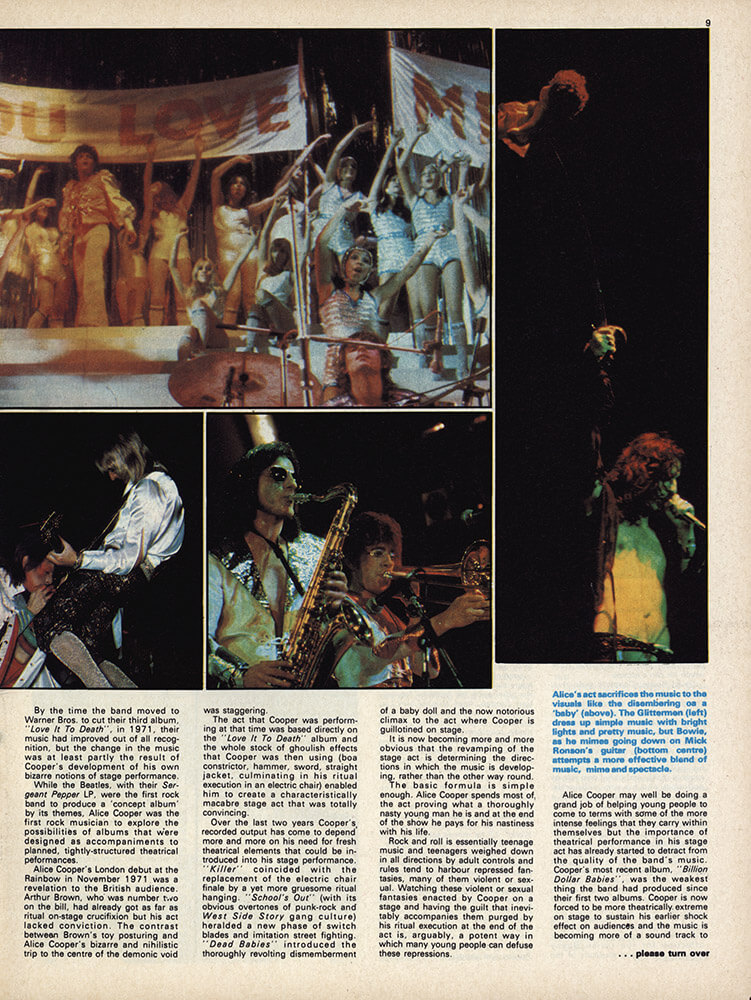

Over the last two years Cooper's recorded output has come to depend more and more on his need for fresh theatrical elements that could be introduced into his stage performance. "Killer" coincided with the replacement of the electric chair finale by a yet more gruesome ritual hanging. "School's Out" (with its obvious overtones of punk-rock and West Side Story gang culture) heralded a new phase of switch blades and imitation street fighting. "Dead Babies" introduced the thoroughly revolting dismemberment of a baby doll and the now notorious climax to the act where Cooper is guillotined on stage.

It is now becoming more and more obvious that the revamping of the stage act is determining the directions in which the music is developing, rather than the other way round.

The basic formula is simple enough. Alice Cooper spends most of the act proving what a thoroughly nasty young man he is and at the end of the show he pays for his nastiness with his life.

Rock and roll is essentially teenage music and teenagers weighed down in all directions by adult controls and rules tend to harbour repressed fantasies, many of them violent or sexual. Watching these violent or sexual fantasies enacted by Cooper on a stage and having the guilt that inevitably accompanies them purged by his ritual execution at the end of the act is, arguably, a potent way in which many young people can defuse these repressions.

Alice Cooper may well be doing a grand job of helping young people to come to terms with some of the more intense feelings that they carry within themselves but the importance of theatrical performance in his stage act has already started to detract from the quality of the band's music. Cooper's most recent album, "Billion Dollar Babies", was the weakest thing the band had produced since their first two albums. Cooper is now forced to be more theatrically extreme on stage to sustain his earlier shock effect on audiences and the music is becoming more of a sound track to his antics and less exciting in itself. The emphasis on theatricality which gave Cooper such enormous freedom at first is now, ironically enough, developing into a straitjacket from which he can't escape.

David Bowie, Cooper's main rival for the 1973 Freak Superstar Title, approaches stage performance in a totally different way. Bowie's chequered career before making it to superstardom (including a spell in Lindsay Kemp's mime troupe and a period founding and running the Beckenham Arts Lab.), the depth of his insights both into the nature of external reality and of his own role as performer and his very substantial talents both as a composer and a lyricist have put him in a position where he can make effective use of theatrical devices onstage without having to sacrifice his music for dramatic effects.

Certainly Bowie is well aware of the importance of spectacle. On his last British tour he was changing costumes a dozen times in a two hour set and each costume change was carried out in a brief thirty-second black out between numbers.

Perhaps surprisingly considering his early association with noted set designer Sean Kenny and his obvious affection for the lavish Busby Berkeley Hollywood musicals of the thirties and forties, Bowie rarely uses elaborate stage sets. However, unlike most rock stars, he does write his own lighting scripts and the attention he devotes to this aspect of his stage act does a lot to enhance the glamour of his performance.

Even now it's still possible to detect many early influences in Bowie's act. His admiration for Anthony Newley, Iggy Stooge, Andy Warhol and Lou Reed (one time member of Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable mixed media roadshow) are all reflected in his stage presentation. But the most obviously theatrical aspect of Bowie's performance is his use of mime.

While he makes considerable use of his hands at all times (on his last tour he appeared for the first time without his traditional 12-string guitar) he only extends the mime on two numbers. On "Width Of A Circle" from "The Man Who Sold The World" LP he mimes fellatio on guitarist Mick Ronson and on "Time" from "Aladdin Sane" he brilliantly enacts a more complex mime of a man who is a captive, finds a closed door and attempts to work his way through it (a routine that is reputedly ripped off from famed trench mime Marcel Marceau).

Unlike Cooper, Bowie is more concerned with sexuality than violence which puts him squarely in the hip grinding mainstream tradition of Presley and Jagger. More important he has never allowed the theatrical elements of his performance to dominate his music and while Cooper has become increasingly cliched in his music, Bowie has continued to break new ground. It's worth remembering that at the end of his 1973 British tour Bowie claimed to be retiring from live performances.

Bowie obviously has an enormous future even if he limits himself to studio work whereas Alice Cooper's career without the impact of his live shows would probably run into instant difficulties.

Performance and spectacle have always been an integral part of rock music and the recent popularity of Bowie and Cooper has shown a healthy movement away from the potential aridity of the studio-orientated rock and roll avante garde.

At the same time the problems that Alice Cooper is now running into clearly demonstrate the difficulties of extending the dramatic scope of rock music beyond a certain point. As Bowie has realised, good live rock and roll music requires sustained concentrated effort from the performers. The implicit theatrical elements in rock can profitably be exploited but if that exploitation comes to dominate the performance it is inevitable that the music itself will ultimately suffer as a result.

The Same Business as Shakespeare?

Don't call it Rock Theatre. Call is Depression Escapism

Author: Ian McDonald

Two years ago you had to have your fringed jacket, moccasins, and Yamaha acoustic. Last year you had to glam it up and swan around, blowing kisses at the guys in the audience. This year you got to have your theatrics, man, haven't you?

One basic Rock Theatrics Kits consists, of (a) three pneumatic lighting-towers, (b) one reflecting-mirror globe, (c) two cardboard aspidistras, (d) half-a-dozen smoke-canisters (or one economy-sized bucket of dry ice), and (e) as many costume changes as your record company's advance will cover.

Get that lot together and you're in the same business as Shakespeare.

* * *

I agree that the word theatre means many disparate, and sometimes contradictory, things at the moment. Straight theatre (classical, post-Ibsen, contemporary), street theatre, dream theatre, community theatre, satirical theatre, Theatre of the Absurd, Theatre of Cruelty, Theatre of Laughter, Theatre of Social Realism ... does it really make any difference whether we add Theatre of Rock?

I think it does. Firstly because it's my contention that it doesn't exist — and, secondly and more relevantly, because the bland acceptance on the part of both performer and audience that there is such a thing as Rock Theatre is contributing to the ever-worsening identity crisis the music's going through right now.

But before we get to why Bowie and Cooper and all aren't New Wave Oliviers, let's try and pinpoint where the phenomenon they embody has come from.

Because the last thing it is is new. I mean, there's more theatre in The Black And White Minstrel Show than there is in Cooper's extravaganza.

It's show-biz, folks. All that's happened this year is that rock has come back out of the Woodstock/Altamont cold into the roar of the cash-registers and the smell of the freshly-inked greenback. Where it started and where it belongs.

What passes for innovation in the sphere of Rock Theatrics is almost always just a rather amateurishly handled gimmick handed down from The Magic Circle or The Talk Of The Town. The current vogue for High Drama At The Local Locarno is merely the natural extension of the antiWoodstock backlash. In 1972 you strutted your stuff and were loud and as uncool as possible; in '73 you do the same thing in 3-D and technicolour — and, of course, with SMOKE-BOMBS!

Never forget the smoke-bombs.

* * *

Okay — granted that none of it hasn't been done before and that even the best effects (like the Floyd's air-crash) are light-years behind, say, Busby Berkley. Does that stop it being theatre? Surely showbiz — even the noisiest, total environmental, sensory glitzkrieg — can still be art (man)?

Well, as I said, there are plenty of conflicting ideas about what theatre is and I wouldn't bother splitting hairs if I didn't think it was important, so here's my list of objections to the nomination of rock 'n' roll into the Thespian academy.

For a start, it's too noisy.

Theatre, if it does nothing else, must set up the environment for a fairly precise level of communication between players and watchers. You've got to be able to follow what the actors are saying and doing — otherwise you might just as well pay money to look at a traffic-jam. Which would be silly.

Live rock relies on a generalized impact which doesn't necessarily entail audible lyrics, singing in tune, or playing the right notes all the way through the song. Rock audiences come to have things done to them, not to have their powers of cerebral acuity tested. If you go to a Who concert your ears get raped (as Pete Townshend would say). They do your brain in before you get so much as a chance to think about thinking.

And they also give you what used to be called a coup de theatre. Just as they go into "Won't Get Fooled Again" and the crowd leaps onto its many feet, a curtain at the back parts to reveal a huge mirror and the audience cheering themselves.

This is technically known as A Special Effect and listed by the property man as A Prop. There is a widespread belief that anything with a prop in it is Theatre. There is no truth in this belief and I urge you to disregard it.

You see, the closest rock gets to the precision of communication current in theatre is when Alice Cooper is led away to be executed for stabbing babies or when David Bowie undoes a zip in midair and shrugs his way through the resultant hole. Mime, in other words.

But mime is very crude communication. At best it can only epitomize; at worst it simplifies to the level of the stereotype.

Since rock is so loud and so far away, the only means by which it can imitate theatre are by the use of props and mime — and it's usually only the former.

Lacking the essential intimacy of the theatrical situation, rock can never hope to produce more than a tiny fraction of the effects and tensions and subtle conventions of design that exist in that form. Even ballet, which lies between rock and real theatre, is based on a matrix the complexity of which makes the Alice Cooper Roadshow look like Wrestling Night at the Baths Hall.

Only a quiet, dynamically-sensitive group like Henry Cow can operate successfully in the zone of theatrics — and they do, supplying incidental music to many productions. But when you get back up to the level of Cooper-Bowie (even Genesis-Hawkwind) you're in the land of show-biz. It's just generalized glamour with a few flash gimmicks and the odd pretentious steal from Wherehouse La Mama thrown in.

* * *

Oh very well, I hear you snore — so rock has nothing much to do with theatre. So what?

I'll tell you.

The theatrical misconception of rock's destiny-for-next-year is but a single facet of the huge problem of inflation currently afflicting the business. Rock has always been a "show" of some kind. It's merely that the difference between seeing Cream at your local icerink in 1967 and gazing through field-glasses at Bowie in Earl's Court, 1973, is not simply one of degree.

Between the two events a mighty transference of image and media attention has passed from The Silver Screen to The Golden Disc. Today's stars aren't blown up good and big for us on 70mm — they have their sound blown up good and big courtesy of several thousand watts of amplification, but they remain physically metamorphosed only by glitter-sprayed suits that catch the spotlight.

Nevertheless Hollywood has given way to Max's Kansas City — and, camp being presently in vogue, the spirit of Cecil B. DeMille is abroad amongst the synthesizers and quadraphonic sound systems and apocalyptic pose-striking of The Superstar Era.

The shift in mass-worship/hysteria from cinemas to rock venues has been paralleled, of course, by at least two other gradual developments: (A) the commercial success of c. 1967 "underground" music, which led to a great deal of indiscriminate financial investment in rock, which led to a competitive bigger is-better ethic; and (B) the more defensible desires of the musicians to expand, the possibilities inherent in the idiom — in the case of Hendrix playing with progressively greater and greater volume (thus necessitating larger and larger halls) or The Pink Floyd wanting to experiment with wound-in-the-round (thereby being one of the first bands to play a bona fide concert venue, the Festival Hall).

Add to this the abrupt mainstream cultural acceptance of rock (e.g., Soft Machine at the Proms, group-orchestra projects, etc.). and a loud, naive nexus of teen psycho-drama and electro technological cabaret is put right there On The Spot.

Rock is embarrassed. It's in the position of the escaping convict pinned against the prison-wall by a dazzling searchlight — and a wave of applause from several thousand sweating palms. It got called Art when "Sgt Pepper" came out, liked it for two or three years, got wise and fled to Woodstock, got rich and therefore endlessly fascinating to the businessmen who manipulate our field of vision, and is now trying to cover its mortification at having to be Art again for the lusting masses by turning its sellout into New Wave chic.

Rock'n'roll decadence. Exciting Times.

* * *

Slade, Glitter, Roxy, Bowie, Mott, Cooper — the best things to happen to rock since ... ? Since they started. You can't cut time off and put a chunk of it in another place. This is the same music as it was in 1955 — only completely different.

Considering The Beatles and Dylan aren't trying any more, rock's doing alright at the moment. And probably someone with a terminal brain tumour has some amazing hallucinations just before he dies. And probably The Roman Empire was at its ritziest just as it was going down for the last time.

Right now rock is simply bigger than its ever been and confused because it knows too much for its own good. It may be cancer or it may be a balloon some guy in a fur coat is blowing out of the window of his Rolls. Whatever it is, the Impersonality Quotient of the music has never been higher and, if we're all going to play bit-parts in the saga of Ziggy Stardust for the sake of historical verisimilitude, we'd do well to hold onto that knowledge.

Don't call it Rock Theatre. Call it Depression Escapism.

The Thirties, The Fifties, The Seventies. Bleak times need bright lights — but much more importantly they need a knowing laugh.

Enjoy — as the American S.F. magazine blurbs used to say.

Enjoy