Article Database

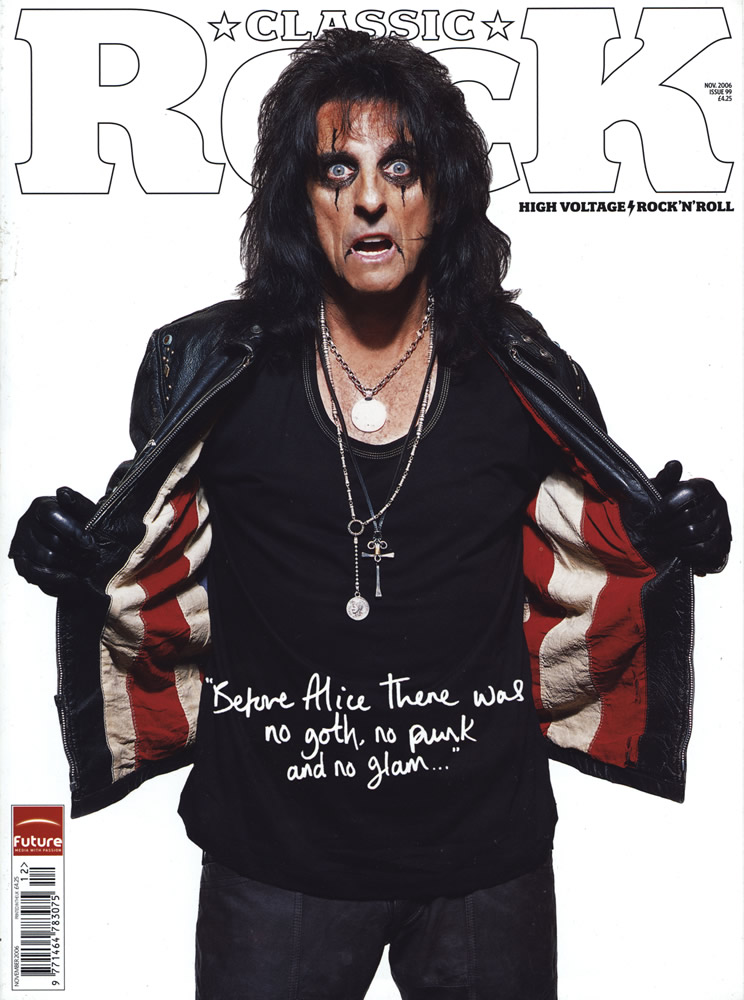

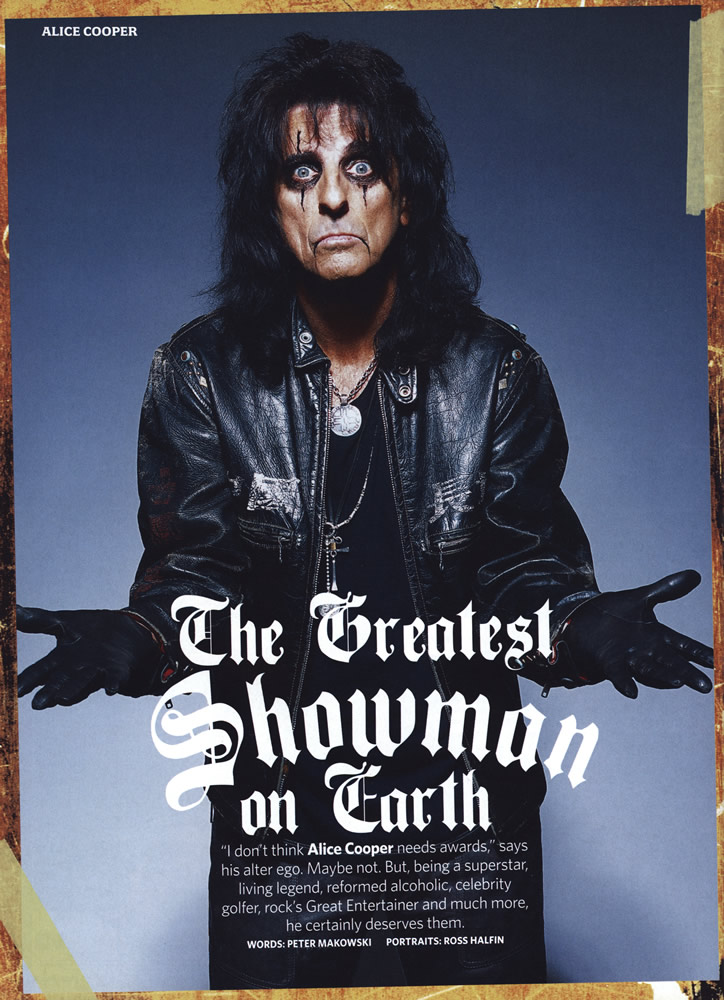

The Greatest Showman on Earth

"I don't think Alice Cooper needs awards," says his alter ego. Maybe not. But, being a superstar, living legend, reformed alcoholic, celebrity golfer, rock's Great Entertainer and much more, he certainly deserves them.

If thesaurus people Roget's ever get it together to produce a Rockathaurus, Alice Cooper will surely be one of the names in the definition of 'rock legend'. Alongside Keith Richards and, obviously, Lemmy, Cooper is without a doubt one of the most iconic figures of rock'n'roll. The grand ghoul of theatre rock, Cooper is among the elite few who have managed to endure and survive an ever-changing, fickle musical industry. The element of shock and awe has subsided over the decades, and he is probably now considered more vaudeville than performance art but, let's face it, there's nothing showbiz has left to offer that could offend today's numbed-out, media-saturated generation; hell, Al Qaeda has taken over in that department. At the heart of it the Alice Cooper experience is still 100 percent pure garage metal cranked to 11, fronted by a larger-than-life rock horror clown. And you can't ask for more than that.

I must admit to being paralysed with fear prior to my meeting with Alice. His music and mythology has always been a huge part of my life. I first heard School's Out at one of the legendary Lyceum all-nighters in 1972. I had, coincidentally, just left school and completed my first week as a fledgling office boy at the late, lamented Sounds magazine. Drunk with the joys of my new-found freedom and half a dozen Special Brews, I stumbled down to the venue in eager anticipation of seeing The J Geils Band "blow the motherfuckin' roof off The Strand, London", as lead vocalist Peter Wolf so delicately put it, in his 100mph Wolfman DJ patois.

Prior to their set, resident hippie Jeff Dexter announced the arrival of this "hot new platter, from the Alice Cooper band, maan". It was getting bleary-eyed late, and the majority of the audience, including yours truly, were horizontal with the joyful effects of various Class C intoxicants. In a mild state of what was known in those days as 'the spinners', to avoid a case of projectile vomiting I focused on one of the many lavishly decorated candelabras above. At this point the opening chords of School's Out boomed from the PA, ripping through my numbed-out sensory system like jagged shards of broken glass tearing at the flesh. I felt a euphoric rush of adrenaline coursing through my veins, and a moment of clarity descended from the heavens above, telling me that my life had just begun. Momentarily I felt free from the shackles of the schooling system, my parents' authoritative regime and the limitations of the licensing laws. It felt like anything was possible. Yet again music, my saviour, had produced something that transcended the normalcy and repetition of everyday life, taking me to a place where there were no boundaries, and even awkward, self obsessed, bespectacled adolescents could change the world.

A few minutes later I passed out. Only to eventually wake up and find that my first pay packet had been lifted. But you know what? It didn't fucking matter. The moment I had experienced was priceless (whereas my wages were a paltry £12.50).

A couple of weeks later the Alice Cooper band made a memorable appearance on Top Of The Pops. They stood out large among the deluge of Tiger Feet and Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheeps, looking like the original Pirates Of The Caribbean, dressed in ephemera that would have made The New York Dolls blush. I vividly remember Neal Smith sat behind the biggest drum kit in the universe, and bass player Dennis Dunaway's reptilian features made him look like a junkie on narcotics from another galaxy; their hair was so long it swept across the studio floor, creating static. Then there was Alice — shit, anyone man enough to give himself a girl's name was okay with me — an amalgam of all the films and American comics I had digested in my youth, with a guttural, rasping voice that betrayed his feminine moniker. At last! A band that looked as good as they sounded.

So here I was, more than three decades later, nervously pacing outside a fittingly expensive and anonymous London hotel in the early hours of the morning, awaiting my audience with the original Emperor of Shock Rock. Having finally summoned the courage to go in, I was immediately led upstairs by a highly efficient PR person who promptly informed me that my interview was to be exactly 45 minutes long, as Alice was leaving the country that afternoon. It was also made very clear that he really wasn't fond of talking about the past. This did not help my fragile state of mind, considering that most of the questions I'd prepared were related to the early years. Cautiously I entered the inner sanctum, a plush suite especially prepared for the interview, and was immediately given a warm greeting by Alice himself, who extended a talon and guided me to a comfortable leather sofa.

The Alice Cooper of the new millennium is discretely made-up, hair dyed black and dressed in comfortable attire. He is still fairly scrawny but glowing with a healthy pallor. He comes over as someone who is very comfortable with himself. It's quite disconcerting, if not totally unsettling, to finally confront the character who disrupted my adolescence and invaded most of my darkest nightmares, and find him to be calm, almost Zen-like. I felt like Clarice Starling finally coming face to face with Hannibal Lecter, only to be blown a kiss and offered some tea and scones. In an attempt to settle my nerves, as an ice-breaker I asked Alice how he felt about winning the prestigious Classic Rock Living Legend Award this year.

"These things usually come at the end of your life, which I hope this is not the case," he cackled. "I don't think Alice Cooper needs awards," he continued, sipping on one of the many Diet Cokes littered around the room. "He certainly doesn't need a Grammy. Alice has made his mark. You cannot go through the history of rock'n'roll without bumping into Alice about seven or eight times, as far as things he started. There was no goth before Alice. There was no punk before Alice. There was no make-up or glam before Alice. I feel that before Alice there was just standard rock. There was a big, blank canvas behind every band. All we did was paint that canvas. I think a lot of people are celebrating him rather than me. Which is okay, he belongs to rock'n'roll."

As you can see, Alice still refers to himself in the third person, even though he changed his name by deed poll in 1974. No longer Vincent Furnier, the Cooper logo is now an incredibly successful franchise for restaurants, a radio show and even Cooperstown — which is probably like Disneyland but with snakes ... and a lot of blood. In fact these days Alice has become a strangely acceptable worldwide phenomenon. No longer splashed over the front pages of the tabloids with his transvestite, chicken-decapitating antics, you're more likely to see him playing in a celebrity golf tournament — albeit wearing a garish salmon pink outfit and looking like an escapee from an early John Waters movie.

A consummate showman, Alice's spiel is a cross between carnival huckster and surreal terrorist. It's no surprise to hear that two of his biggest influences were two former friends, Salvador Dali and Groucho Marx.

"The band were big Dali fans," he recalled. "We thought: 'Why can't you do surrealism on stage? Why can't you take a crutch, a snake and a guillotine, put all those things together and not necessarily have to make sense?' Dali loved my shows because he thought they were so confusing and made no sense at all. And before Groucho died, he told me that Alice was the last chance for vaudeville."

With limited time, rather than trawl through every aspect of Cooper's history (which is already more than adequately documented) I decided to focus on asking him about some key moments in his life and career.

"Ask me anything you want," he snarled. "Fire away. I'm good at these things."

Going back to the beginning, what were you like as a child?

I wasn't a placid kid. I wasn't the kind who just sat around. I played all the sports, even though I was a skinny little kid.

Then all of a sudden I had this burst appendix that took me out for about two years. Getting through that was a miracle in my life. That was God saying: "You're not going out yet. I have something better for you." Which might not even be Alice Cooper. I should have been dead. They took a lot of poison out of me. I only weighed 80 pounds. They said that would have killed three elephants.

What were your earliest influences?

I was from a generation that was bought up by TV. The TV was our babysitter. Look at my music and you will find TV themes coming up all the time. We did a song called Unfinished Sweet about a guy who gets his teeth pulled and suddenly starts dreaming he's a spy. During the guitar break we have the theme from The Man From Uncle, I Spy and James Bond. We've used West Side Story. There are few rock bands that are as heavy, dastardly and villainous as Alice Cooper who would do the Jet Song. It's in our psyche because we watch TV. I'll be writing a song and all of a sudden this little reference from some obscure TV show will come in, which makes sense to me. I'll say put it in there, because it's a part of us. When you write you're flushing out all the stuff that's built up inside you. Whatever comes out comes out. I watch a lot of movies and TV.

You still do that?

More than I do rock'n'roll. I don't run out and buy the next big album, cos I know I'm going to hear that stuff anyway. Being in rock'n'roll I almost move away from listening to everybody, unless it's something interesting. The first time I heard Jet I went out and bought that album, because I think it's what garage rock should be. Here's a new band that sounds like the old Small Faces. The White Stripes are intriguing because it's so unproduced that it's great, it takes me back to 1968.

Is it true that one label wanted to sign the original Alice Cooper band as long as they got rid of you?

Yeah. Original Sound Records had a band called Music Machine. They had a huge hit with a song called Talk Talk. They auditioned us, and said: "We want you to be the new Music Machine, but you've got to get rid of your lead singer." We said we don't want to be the new Music Machine, we want to be us. So we walked away from that one.

Everybody turned us down. Frank Zappa was the only one that looked at us and said: "Okay, I'm putting a record company together. I've got Wild Man Fischer, The GTO's, I've got all these people that are freaks of the street." His motto was 'No Commercial Potential'. Frank lived to see Alice Cooper become the biggest band in the world. But he let us slip through his hands. He could have kept us, but he saw us as a joke. We saw us as a joke, but as a really good band too. What people didn't realise is we would rehearse 10 hours a day — nine hours on the music and maybe an hour on the theatrics. Theatrics were just secondary to us; we knew we had to be as good as Led Zeppelin. The music is the engine to everything that I do.

So where did the theatrics come from?

I think the theatricality came from the fact that Dennis [Dunaway, bassist] and I were both art majors and journalist majors. We understood sensationalism. We understood how it worked in the press. Alice Cooper the character, the person I invented, rock's premier villain, is actually separate from me. I created him as my favourite rock star. I said: "I'm going to invent my favourite rock star. Who's it going to be?" So I designed this character that would be a villain, but he would be funny and scary. He would be swashbuckling, but he would be definitely darker than anybody else out there.

I look at our shows as being almost Shakespearian. I don't care what reaction I get, as long as I get a reaction. And I let the audience use their imagination. If we both look at a Dali painting, we're both going to give different values to the things we see. If you took 10 people coming out of an Alice Cooper show and asked them what they saw, they would say 10 different things. And some of the stuff probably never happened, they invented it themselves — that's great! How much more art is that? We gave them great rock'n'roll, but they actually attached their imagination. We actually turned the audience into artists.

Your early stage shows were outrageous and anarchic. There's a story going round that your first manager, Shep Gordon, signed you because you had the ability to clear a room. Is that true?

Oh sure [laughs]. We played [comedian] Lenny Bruce's birthday party in LA with The Doors and Janis Joplin. We were the house band there, along with Pink Floyd. There were 6,000 groovy people on acid, a typical stoned LA audience. Alice Cooper comes on stage in full clown make-up and we kick off with The Who's Out In The Street. It's the loudest thing anybody has heard. It was like Springtime For Hitler in The Producers.

The audience stood there with their mouths wide open. And pretty soon that's translating into the acid through to their brains, telling them to get out of the place. We were aggressive. I loved it! They were leaving by the droves. We were the band that people would come and see just so they could leave. We did not fit into LA. The Doors were very LA. They were great. They were the first people to take us under their wing. In those days I hung out with Jim Morrison. I really liked the guy but he had a negative effect on me. He believed that you had to live the role at all times, and I began to pick that up. I started to go out in my leather, do outrageous stuff, get into fights, all the things I thought Alice should do. Jimi Hendrix became one of our guys. He was one of the people who came to our rescue a few times. But we couldn't fit in. And once we realised that we couldn't get any more gigs in LA, we decided that the first place we got a standing ovation we're going to move to.

Which took you to Detroit?

We went to Michigan and played a festival to 300,000 rock and rollers. We played with Iggy & The Stooges and The MC5. When we got up there the audience went crazy, they erupted, because we were louder than The Stooges and The MC5. And we were more obnoxious. And when they found out I was born in Detroit, I was The King.

We moved to Detroit and played with Iggy and Ted Nugent every weekend. It was the greatest rock family you have ever seen. If there was a fight all the bands would go out there and help, cos we were brothers. That was Detroit, the toughest city in America. If you were outside the music world and looked like us, you would get killed. That's what was great, we felt so at home in Detroit. That's where Eighteen broke, that's what launched us.

The Detroit sound was one of the catalysts for punk rock in the UK, so it's quite fitting that Johnny Rotten got his job in The Sex Pistols by miming to one of your songs.

That's right. The only band Johnny Rotten didn't hate was Alice Cooper. People fail to see the humour in The Sex Pistols. They were funny. They were funnier than The Monkees.

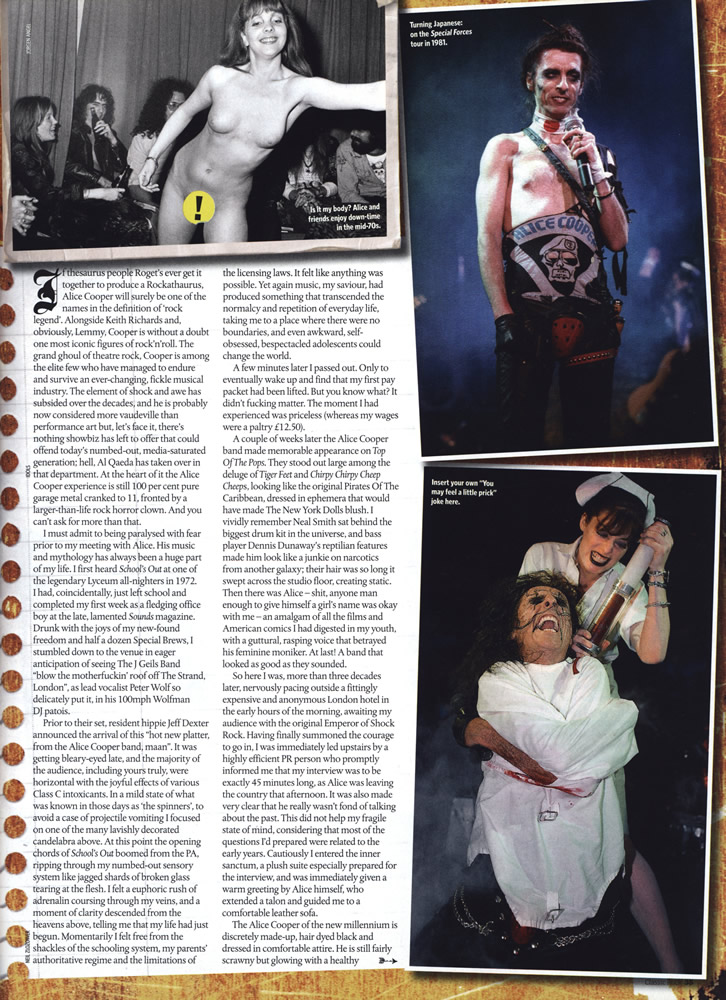

You gave up booze in the late 70s, but then had a spectacular fall off the wagon around 1981 during the Special Forces tour where you looked like a Belsen victim. What happened?

I looked the scariest I've ever seen Alice. I couldn't eat; I was drinking myself into insanity. It got so I never went anywhere without a bottle. That fucking drink became my best friend. And yet I listen to that album and it was some of my most interesting music. I listen to songs like Zipper Catches Skin, Flush The Fashion and think they were great. But I have no memory of writing them. Don't remember a thing. Total blackout.

I look at the Special Forces show and I think 'that's the scariest thing I've ever seen, it's the scariest lead singer I've ever seen'. And it's me! It's my monster. It's my Frankenstein and I've lost total control of it. To this day I can't remember any gigs. Maybe I've subjectively erased it. And I somehow survived it. Again I don't know why God would intervene and somehow protect me. I should have been busted a million times; I was Pete Doherty times 10. I'm indestructible.

I really believe that we never see the big picture, we only see what's going on now and we can only take two steps. There's quite a few times where divine intervention has been a huge thing in my life. I was almost dead from drinking myself to death, and when I came out of hospital I was not cured from alcoholism, I was healed from it. You need a will to live. There is a point where the doctor says: "It's very simple: you either quit drinking or die." You either jump off the building, or don't jump off the building — make a choice. I came out of there and never had another thought about drinking. I think that tobacco and alcohol age you more than anything else. Probably speed does too. I've never smoked and I quit drink, which is probably why I have 20 albums under my belt while a lot of my peers are dead.

Talking about peers, original Alice Cooper band guitarist Glen Buxton tragically died a few years back. Wasn't he a big influence on you and the rest of the band?

He smoked, he drank, he was ... what was the name of the character in Catcher On The Rye [Holden Caulfield]? He was some kind of outcast James Dean character. The rest of us were jocks, we were star athletes. I went to church every Sunday and Wednesday night. I couldn't be more wholesome. All the guys in the band came from good homes. So there was no reason for us to end up being Alice Cooper, but that's what came out [laughs]. Glen was the guy that would get caught smoking in the bathroom. He was our Keith Richards. He always had a weapon on him of some sort. He was a totally agitated youth.

You could say that he was a component of your alter ego?

Yeah, absolutely. I'm the only one who got Glen. I understood him. It was important for him to spit in the face of society. It was important for him not to fit in. And in the end it killed him. He wasn't ever going to give up. Dennis, Neal [Smith, drummer] and everybody quit doing what they were doing 25 years ago; Glen just kept going full blast.

Did you see him before he died?

Yeah. The last time I saw him he came backstage to a show. Somebody said: "Glen's here." I thought: "Great." Then these two girls came in followed by this little old man who looked about 75 years old — it was Glen. I almost didn't recognise him. We were the same age. He smoked and drank himself into being an old man.

A living legend. A survivor. What is the secret to your longevity?

A lot of it has to do with realising that I'm only Alice Cooper for 90 minutes on stage, and the rest of the time I can just be me. Sounds silly, but not understanding that almost killed me.

In this business you have to learn to ride the roller coaster of success and failure. You can be the biggest band in the world, and then you're not. The only thing a guy like me can do is put their best effort into the next album. Who's going to buy it? Well, classic artists never get played on the radio, so these albums are for my fans.

I take my loyal followers to a lot of different places. In the early days School's Out and Billion Dollar Babies were very general, just great rock songs. Love It To Death, Killer, we had a lot of hits during those days, which was unusual. Here was the most outrageous band, with hits! Well, that just didn't happen. Oingo Boingo never had a hit, Bonzo Dog and Zappa never had a hit; here was a band that was weirder having hit after hit. We knew songs like Eighteen would affect everybody. It was voted one of the 50 most important songs ever written.

When I got into my later albums I realised that I wasn't going to get played on the radio. Neither were The Rolling Stones, McCartney or any other classic rock bands. So I'm making those albums for staunch Alice Cooper fans. The last two albums were recorded live in the studio — I want to show off the band. Even though the focal point is Alice Cooper, I always look at it as a band effort. I believe in new talent. I don't know everything, I just have this legacy behind me of having a lot of good ideas. I am not a despot, even though I have the last say.

Which of your albums is your favourite?

It's like asking who's your favourite child; they all have their own different personalities. Love It To Death was the most pivotal album, because it was the first album that introduced us into the rock arena. Pretties For You and Easy Action were great psychedelic albums but really didn't have any chance. School's Out, Billion Dollar Babies, Welcome To My Nightmare — ask anyone what their favourite album is and it will be one of those. Musically the best album is From The Inside. Best garage rock album: Dirty Diamonds. If I were going to pick one to put in a vault that represented Alice it would be either Love It To Death or School's Out.

And your least favourite?

The first live album [The Alice Cooper Show, 1977]. I just hated that album. I was never more depressed in my life. The tour was over; I was ready to go into a sanatorium. I'm home after two years, and the record company calls up to say that we have to give them a live album. I said I can't, I need to be in a mental hospital right now for alcohol. I was literally forced. The band played great, but it was pure torture.

Time up, Alice gets up shakily, bent over like an old man. "Oh yes, I remember the old days, sonny. It all started in 1948 ... " His voice trails in mocking laughter as he hobbles out of the room to join his daughter, Calico, for a quick shopping fix before heading to the airport.

Always the showman, Alice Cooper's tongue seems to be eternally embedded in a distinctly hollow cheek. As I made my exit, still an impressionable fan, I pondered over a suitable epilogue for this feature, and immediately remembered a quote when one interviewer asked him how long he planned to carry on performing. "Alice will go on forever," Alice replied. "I'm an American tradition. I mean, how can you seriously not like Alice? It's like saying you don't like boa constrictors."

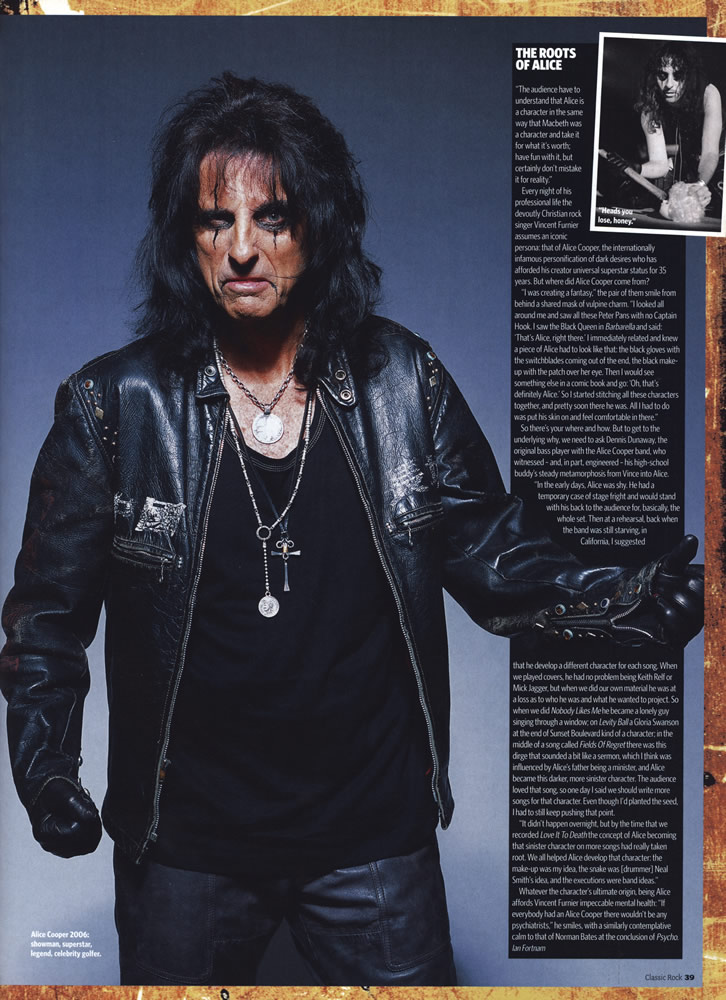

The Roots of Alice Cooper

"The audience have to understand that Alice is a character in the same way that Macbeth was a character and take it for what it's worth; have fun with it, but certainly don't mistake it for reality."

Every night of his professional life the devoutly Christian rock singer Vincent Furnier assumes an iconic persona: that Alice Cooper, the internationally infamous personification of dark desires who has afforded his creator universal superstar status for 34 years. But where did Alice Cooper come from?

"I was creating a fantasy," the pair of them smile from behind a shared mask of vulpine charm. "I looked all around me and saw all these Peter Pans with no Captain Hook. I saw the Black Queen in Barbarella and said: 'That's Alice, right there.' I immediately related and knew a piece of Alice had to look like that: the black gloves with the switchblades coming out of the end, the black make-up with the patch over her eye. Then I would see something else in a comic book and go: 'Oh, that's definitely Alice.' So I started stitching all these characters together, pretty soon there he was. All I had to do was put his skin on and feel comfortable in there."

So there's your where and how. But to get to the underlying why, we need to ask Dennis Dunaway, the original bass player with the Alice Cooper band, who witnessed — and, in part, engineered — his high-school buddy's steady metamorphosis from Vince into Alice.

"In the early days, Alice was shy. He had a temporary case of stage fright and would stand with his back to the audience for, basically, the whole set. Then at a rehearsal, back when the band was still starving, in California, I suggested that he develop a different character for each song. When we played covers, he had no problem being Keith Relf or Mick Jagger, but when we did our own material he was at a loss as to who he was and what he wanted to project. So when we did Nobody Likes Me he became a lonely guy singing through a window; on Levity Ball a Gloria Swanson at the end of Sunset Boulevard kind of character; in the middle of a song called Fields of Regret there was this dirge that sounded a bit like a sermon, which I think was influenced by Alice's father being a minister, and Alice became this darker, more sinister character. The audience loved that song, so one day I said we should write more songs for that character. Even though I'd planted the seed, I had to still keep pushing that point.

"It didn't happen overnight, but by the time that we recorded Love It To Death the concert of Alice becoming that sinister character on more songs had really taken root. We all helped Alice develop that character: the make-up was my idea, the snake was [drummer] Neal Smith's idea, and the executions were band ideas."

Whatever the character's ultimate origin, being Alice affords Vincent Furnier impeccable mental health. "If everybody had an Alice Cooper there wouldn't be any psychiatrists," he smiles, with a similarly contemplative calm to that of Normal Bates at the conclusion of Psycho

Ian Fortnam

Classic Cooper

Ian Fortnam looks at six of Mr Furnier's finest

LOVE IT TO DEATH

WARNER BROS, 1971

Following a pair of feet-finding albums for Frank Zappa's Straight label, the classic line-up of the Alice Cooper group (completed by Glen Buxton, Michael Bruce, Dennis Dunaway and Neal Smith) signed to Warners. Their major-label debut represented a quantum leap forward; a macabre theatrical masterpiece that spawned both the epic, gothic drama of The Ballad of Dwight Fry and the priceless, pop chart-conquering concision of Eighteen.

KILLER

WARNER BROS, 1971

A short, sharp, deliciously dark song cycle written with a spectacular stage show in mind, Killer set Alice Cooper's phenomenal Stateside success in stone. Its perfectly crafted musical core of bitter-sweet, poison-laced Beatles melodies and evocative, cautionary tales of delinquency, depravity and death was outstanding in itself. Presented in tandem with a cannily choreographed horror show that concluded with Cooper's notorious 'hanging', it was irresistible. Under My Wheels, Halo Of Flies, Dead Babies; here was coal-black gallows humour in every sense.

SCHOOL'S OUT

WARNER BROS, 1972

Something of a flawed masterpiece, School's Out can be forgiven all it's minor shortcomings thanks to an iconic title track that just about defines classic rock. In parts a gritty, gutter-glam update of West Side Story, in others an unalloyed feast of twisted nostalgia for the old Alma Mater, the album might stumble to an inauspicious conclusion with its overblown instrumental Grande Finale, but it certainly has its moments. And what moments: My Stars, with its epic wall-of-sound production gloss, is simply awe-inspiring.

BILLION DOLLAR BABIES

WARNER BROS, 1973

The dynamic scope of Billion Dollar Babies (produced by Bob Ezrin) casually surpassed all that Alice Cooper had previously delivered. From the triumphal opening salvs of Hello Hooray to the exquisitely crafted code of shock-rocking hymn to necrophilia I Love The Dead, here was an album that totally vindicated the contemporary rock media's unanimous embrace of Alice as the genre's brightest star. B$B gave the band their first No.1 album.

WELCOME TO MY NIGHTMARE

ATLANTIC, 1975

Having dispensed with the services of Bruce, Dunaway, Smith and Buxton following the tepid reception accorded to B$B's relatively disappointing successor, Muscle of Love, Alice regrouped with Bob Ezrin to deliver his most ambitious and theatrical production to date. While Detroit garage grit was replaced with slickness of world-class session players, Cooper boundless creativity endowed The Black Widow and the title track with switchblade sharpness. Feminist anthem Only Women Bleed even produced plaudits from some of Cooper's harshest critics.

THE EYES OF ALICE COOPER

SPITFIRE, 2004

The passing years saw a post-addiction Cooper exploring a variety of musical vistas, some surprising (Flush The Fashions's new romanticism; Brutal Planet's nu-metal), some not so (a late-80s hair metal rebirth that peaked with '89's Poison mega-hit), but artistically speaking it wasn't until he returned to his garage rock roots that he truly delivered a stone-cold classic. The Eyes...found Alice fronting a down-and-dirty rock band for the first time in 30 years.