Article Database

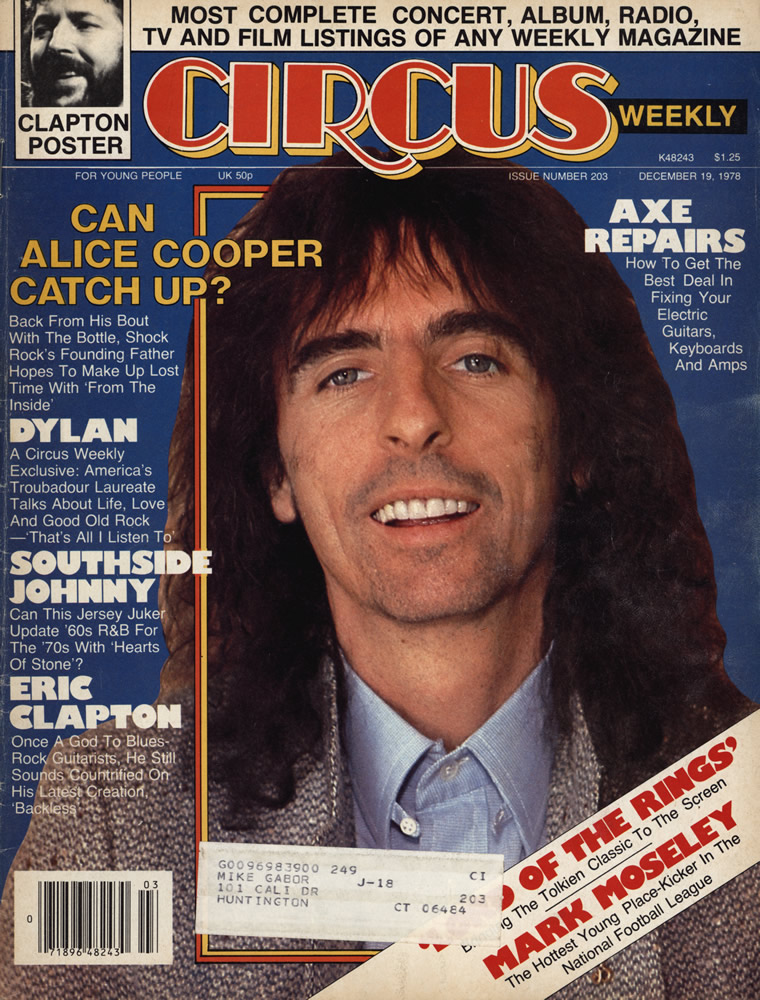

Alice Cooper Goes Straight

Sober, he writes songs of the asylum

Keith Moon was probably the greatest life-lover I've ever known. He didn't want to go to sleep, he loved life so much. The thing is, he didn't use any wisdom with it. He could've been just as crazy and had just as good a time if he'd taken a look at what was happening to his body."

Death, to Alice Cooper, is a subject that has concerned him through his whole career. "I'll be making fun of death forever," he says with a grin. "But I took a look at what was happening to me, and I said 'I don't have to kill myself to go down in history. Forty years from now, when kids are studying history, I'll be one of the literary heroes, like Mick Jagger or Bruce Springsteen. And I don't have to die young to do it.' But I came pretty close to it. The doctors said I'd be dead now if I hadn't stopped drinking."

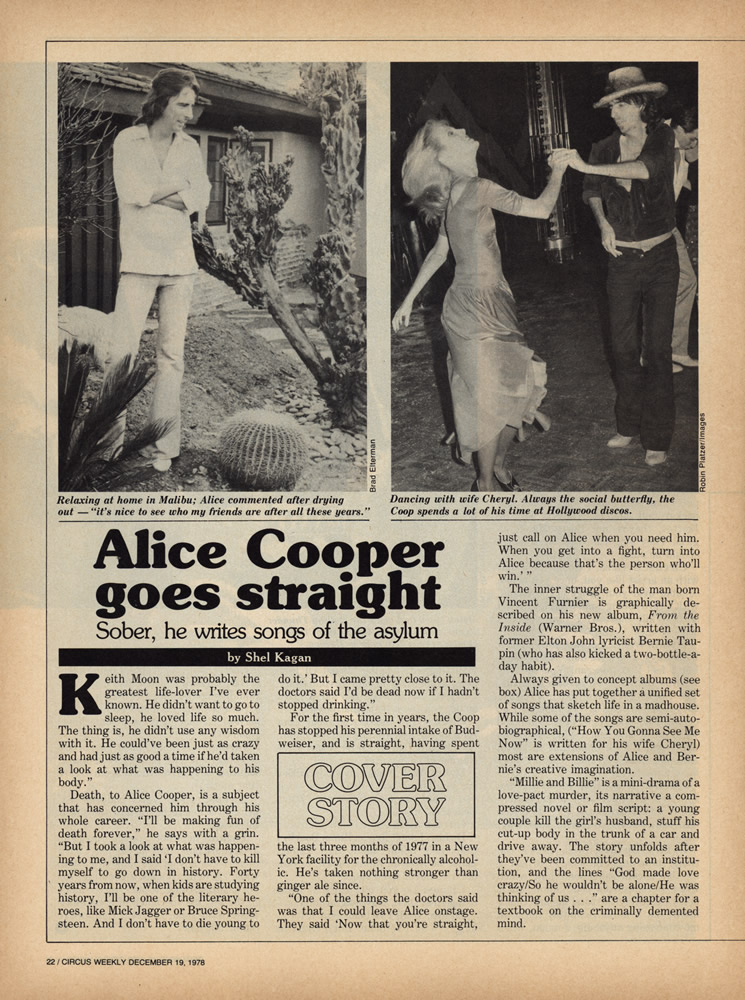

For the first time in years, the Coop has stopped his perennial intake of Budweiser, and is straight, having spent the last three months of 1977 in a New York facility for the chronically alcoholic. He's taken nothing stronger than ginger ale since.

"One of the things the doctors said was that I could leave Alice onstage. They said 'Now that you're straight, just call on Alice when you need him. When you get into a fight, turn into Alice because that's the person who'll win.' "

The inner struggle of the man born Vincent Furnier is graphically described on his new album, From the Inside (Warner Bros.), written with former Elton John lyricist Bernie Taupin (who has also kicked a two-bottle-a-day habit).

Always given to concept albums (see box) Alice has put together a unified set of songs that sketch life in a madhouse. While some of the songs are semi-autobiographical, ("How You Gonna See Me Now" is written for his wife Cheryl) most are extensions of Alice and Bernie's creative imagination.

"Millie and Billie" is a mini-drama of a love-pact murder, its narrative a compressed novel or film script: a young couple kill the girl's husband, stuff his cut-up body in the trunk of a car and drive away. The story unfolds after they've been committed to an institution, and the lines "God made love crazy/So he wouldn't be alone/He was thinking of us ... " are a chapter for a textbook on the criminally demented mind.

The album's anthem is "Inmates," in which Alice rallies all of the nut cases of the world, the ones with "roller coaster brains" who destroy innocent people. His vision is broad enough to show compassion, as he calls the mentally wounded "the fragile elite" while another character in the song dismisses them as "lunatics."

The fragile elite doesn't just refer to inmates, he told Circus Weekly. "That includes great artists like Hendrix, Joplin, Jim Morrison. Though they seemed bigger than life and stronger, they were very fragile inside, or they wouldn't have died so tragically."

Guest instrumentalists on Inside include Steve Lukather, Jeff and Steve Porcaro of Toto, Rick Nielsen of Cheap Trick, and vocalists Kiki Dee and Clapton cohort Marcy Levy.

Most of the cuts were pieced together in a matter of days, and some in a few hours. "Between us Bernie and I have done 35 albums," notes Cooper of the collaboration, "which really helps in cutting down the bullshit. We would look at each other and know immediately if the song was a dog. When I was drinking I had all kinds of self doubt. There's so many caverns in your mind that hold all sorts of garbage things. Now I just naturally know when something's right or not."

"Working with Alice is a totally different experience than working with Elton," says Taupin. "Alice and I go everywhere together — we're pals. Elton and I were a little more distant. Also, I wrote the lyrics alone for Elton, while Alice and I work on lyrics together; it's a closer relationship.

"We work well under pressure — writing early in the morning in order to have a song ready to go into the studio that night.

"We lived, slept and breathed the project," says the Lincolnshire-born ex-Englishman (he's lived in Los Angeles since 1971). "So much so that one night in the studio [producer] David Foster's wife Becky came in with some food and said, casually, 'Pope's dead.' We fell down laughing because we knew he'd just been named. Only later did we realize she wasn't kidding."

Born in Detroit in 1948, Alice moved around the country with parents, his father finally settling in Phoenix as an aerospace technician. The elder Furmer was also a minister in the Mormon Church, a heritage against which the young Vincent was to rebel in his teens when, during a Ouija board session, a 16th century girl named Alice Cooper, sister of a witch, repeatedly said "Alice Cooper is Vincent Furnier."

Beginning as the Earwigs (one single: "Nobody Likes Me"), then as the Spiders and still later as the Nazz (though Todd Rundgren had appropriated that name already) the group known as Alice Cooper left Cortez High School in Arizona and migrated to Los Angeles, where they developed an ability to empty clubs after only a song or two. Among those who remained were Shep Gordon, who still manages Alice after 11 years, and Frank Zappa, who signed the fledgling group because they were more outrageous than he was.

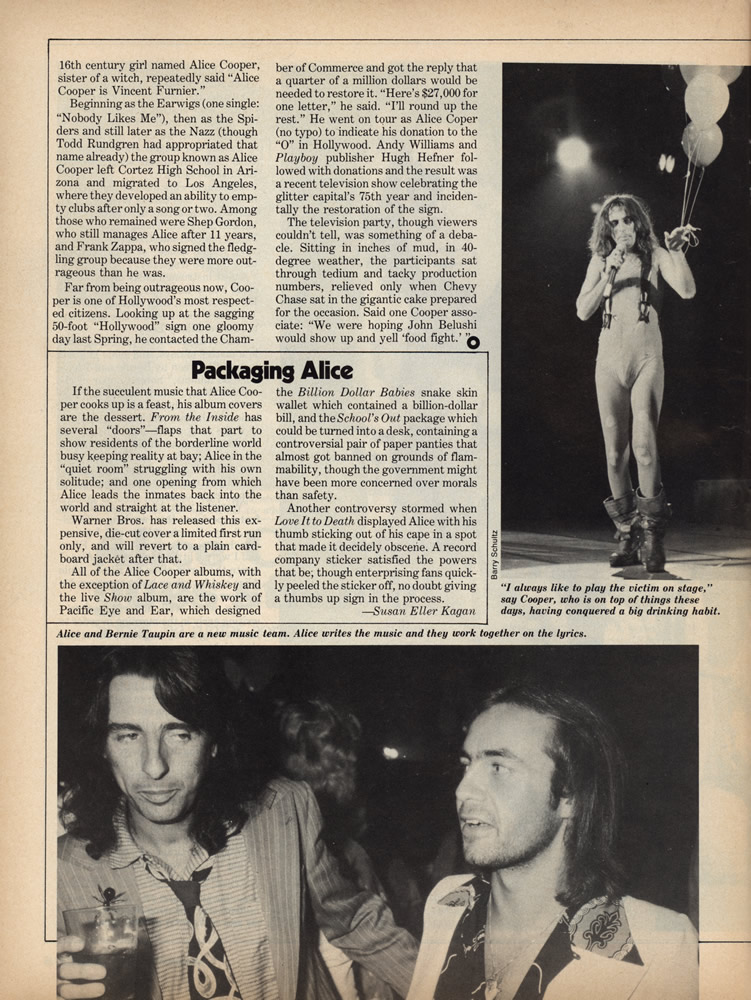

Far from being outrageous now, Cooper is one of Hollywood's most respected citizens. Looking up at the sagging 50-foot "Hollywood" sign one gloomy day last Spring, he contacted the Chamber of Commerce and got the reply that a quarter of a million dollars would be needed to restore it. "Here's $27,000 for one letter," he said. "I'll round up the rest." He went on tour as Alice Coper (no typo) to indicate his donation to the "O" in Hollywood. Andy Williams and Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner followed with donations and the result was a recent television show celebrating the glitter capital's 75th year and incidentally the restoration of the sign.

The television party, though viewers couldn't tell, was something of a debacle. Sitting in inches of mud, in 40-degree weather, the participants sat through tedium and tacky production numbers, relieved only when Chevy Chase sat in the gigantic cake prepared for the occasion. Said one Cooper associate: "We were hoping John Belushi would show up and yell 'food fight.' “

Packaging Alice

Author: Susan Eller Kagan

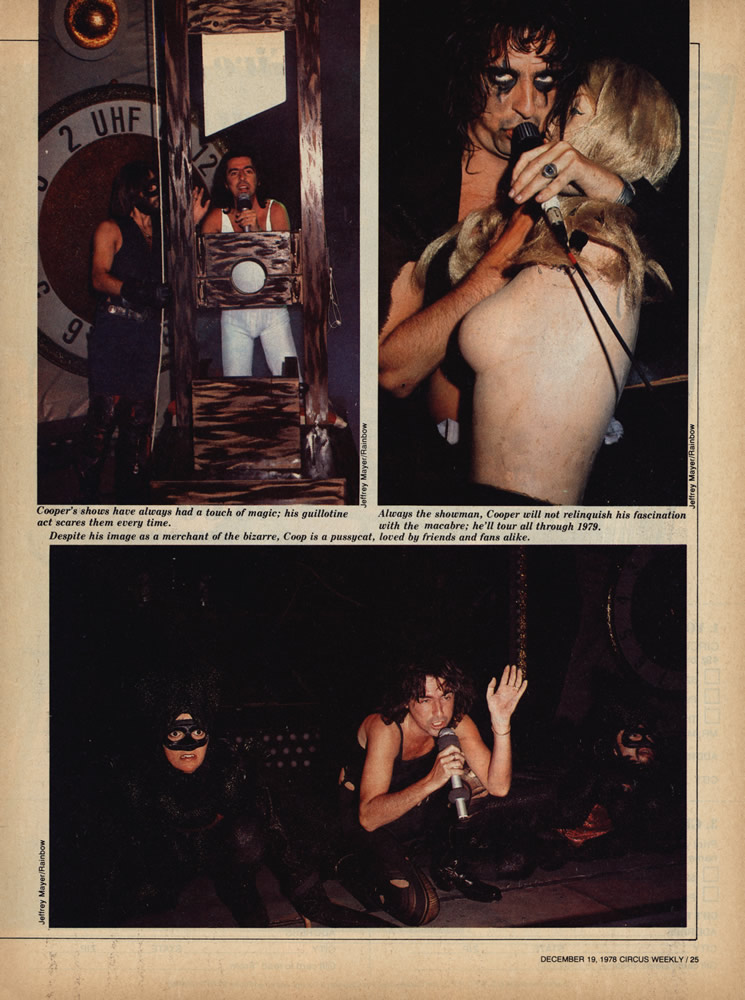

If the succulent music that Alice Cooper cooks up is a feast, his album covers are the dessert. From the Inside has several "doors"—flaps that part to show residents of the borderline world busy keeping reality at bay; Alice in the "quiet room" struggling with his own solitude; and one opening from which Alice leads the inmates back into the world and straight at the listener.

Warner Bros. has released this expensive, die-cut cover a limited first run only, and will revert to a plain cardboard jacket after that.

All of the Alice Cooper albums, with the exception of Lace and Whiskey and the live Show album, are the work of Pacific Eye and Ear, which designed the Billion Dollar Babies snake skin wallet which contained a billion-dollar bill, and the School's Out package which could be turned into a desk, containing a controversial pair of paper panties that almost got banned on grounds of flammability, though the government might have been more concerned over morals than safety.

Another controversy stormed when Love It to Death displayed Alice with his thumb sticking out of his cape in a spot that made it decidedly obscene. A record company sticker satisfied the powers that be, though enterprising fans quickly peeled the sticker off, no doubt giving a thumbs up sign in the process.