Article Database

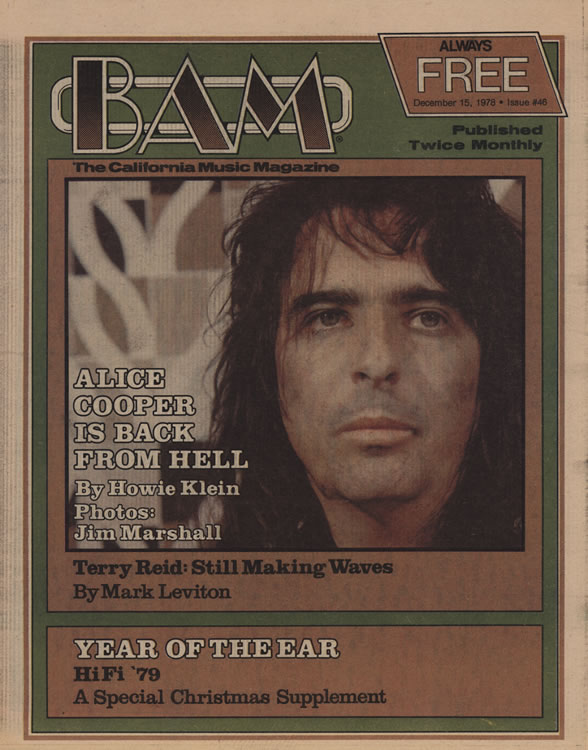

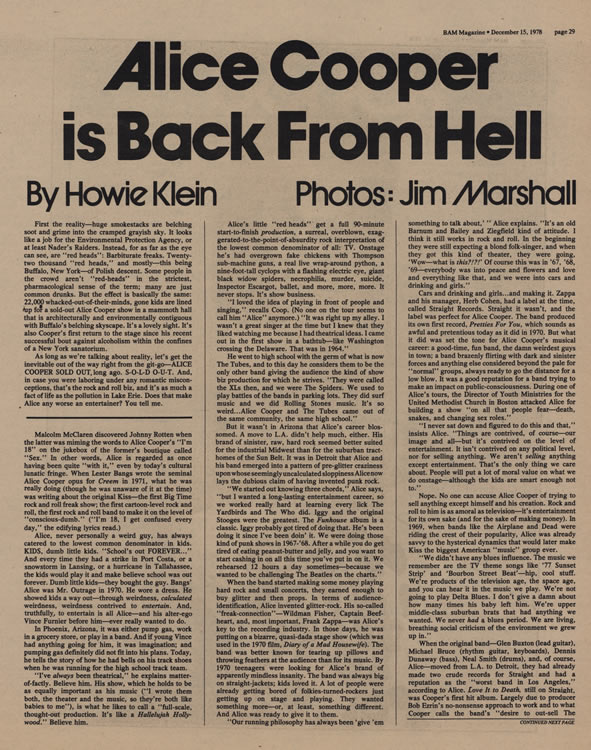

Alice Cooper is Back From Hell

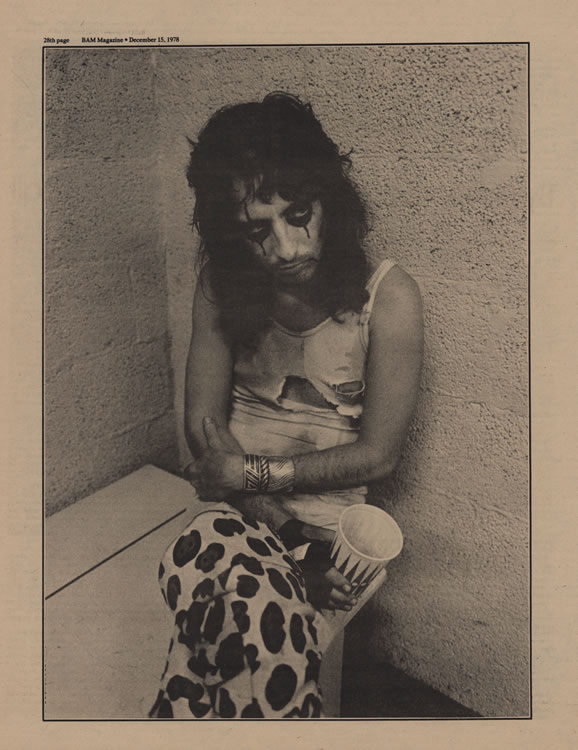

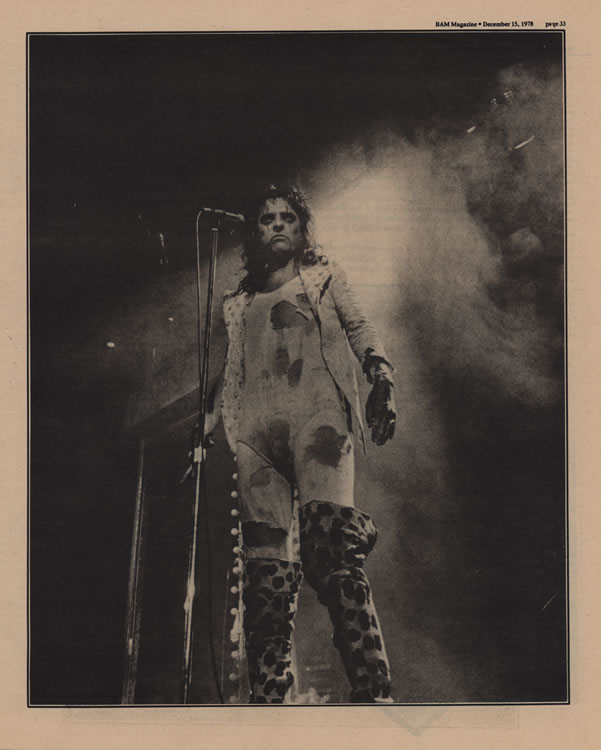

First the reality — huge smokestacks are belching soot and grime into the cramped grayish sky. It looks like a job for the Environmental Protection Agency, or at least Nader's Raiders. Instead, for as far as the eye can see, are "red heads": Barbiturate freaks. Twenty two thousand "red heads," and mostly — this being Buffalo, New York — of Polish descent. Some people in the crowd aren't "red-heads" in the strictest, pharmacological sense of the term; many are just common drunks. But the effect is basically the same: 22,000 whacked-out-of-their-minds, gone kids are lined up for a sold-out Alice Cooper show in a mammoth hall that is architecturally and environmentally contiguous with Buffalo's belching skyscape. It's a lovely sight. It's also Cooper's first return to the stage since his recent successful bout against alcoholism within the confines of a New York sanatorium.

As long as we're talking about reality, let's get the inevitable out of the way right from the git-go — ALICE COOPER SOLD OUT, long ago. S-O-L-D O-U-T. And, in case you were laboring under any romantic misconceptions, that's the rock and roll biz, and it's as much a fact of life as the pollution in Lake Erie. Does that make Alice any worse an entertainer? You tell me.

Malcolm McClaren discovered Johnny Rotten when the latter was miming the words to Alice Cooper's "I'm 18" on the jukebox of the former's boutique called "Sex." In other words, Alice is regarded as once having been quite "with it," even by today's cultural lunatic fringe. When Lester Bangs wrote the seminal Alice Cooper opus for Creem in 1971, what he was really doing (though he was unaware of it at the time) was writing about the original Kiss — the first Big Time rock and roll freak show; the first cartoon-level rock and roll, the first rock and roll band to make it on the level of "conscious-dumb." ("I'm 18, I get confused every day," the edifying lyrics read.)

Alice, never personally a weird guy, has always catered to the lowest common denominator in kids. KIDS, dumb little kids. "School's out FOREVER ... " And every time they had a strike in Port Costa, or a snowstorm in Lansing, or a hurricane in Tallahassee, the kids would play it and make believe school was out forever. Dumb little kids — they bought the guy. Bangs' Alice was Mr. Outrage in 1970. He wore a dress. He showed kids a way out — through weirdness, calculated weirdness, weirdness contrived to entertain. And, truthfully, to entertain is all Alice — and his alter-ego Vince Furnier before him — ever really wanted to do.

In Phoenix, Arizona, it was either pump gas, work in a grocery store, or play in a band. And if young Vince had anything going for him, it was imagination; and pumping gas definitely did not fit into his plans. Today, he tells the story of how he had bells on his track shoes when he was running for the high school track team.

"I've always been theatrical," he explains matter-of-factly. Believe him. His show, which he holds to be as equally important as his music ("I wrote them both, the theater and the music, so they're both like babies to me"), is what he likes to call a "full-scale, thought-out production. It's like a Hallelujah Hollywood." Believe him.

Alice's little "red heads" get a full 90-minute start-to-finish production, a surreal, overblown, exaggerated-to-the-point-of-absurdity rock interpretation of the lowest common denominator of all: TV. Onstage he's had overgrown fake chickens with Thompson sub-machine guns, a real live wrap-around python, a nine-foot-tall cyclops with a flashing electric eye, giant black widow spiders, necrophilia, murder, suicide, Inspector Escargot, ballet, and more, more, more. It never stops: It's show business.

"I loved the idea of playing in front of people and singing," recalls Coop. (No one on the tour seems to call him "Alice" anymore.) "It was right up my alley. I wasn't a great singer at the time but I knew that they liked watching me because I had theatrical ideas. I came out in the first show in a bathtub — like Washington crossing the Delaware. That was in 1964."

He went to high school with the germ of what is now The Tubes, and to this day he considers them to be the only other band giving the audience the kind of show biz production for which he strives. "They were called the XLs then, and we were The Spiders. We used to play battles of the bands in parking lots. They did surf music and we did Rolling Stones music. It's so weird ... Alice Cooper and The Tubes came out of the same community, the same high school."

But it wasn't in Arizona that Alice's career blossomed. A move to L.A. didn't help much, either. His brand of sinister, raw, hard rock seemed better suited for the industrial Midwest than for the suburban tract homes of the Sun Belt. It was in Detroit that Alice and his band emerged into a pattern of pre-glitter craziness upon whose seemingly uncalculated sloppiness Alice now lays the dubious claim of having invented punk rock.

"We started out knowing three chords," Alice says, "but I wanted a long-lasting entertainment career, so we worked really hard at learning every lick The Yardbirds and The Who did. Iggy and the original Stooges were the greatest. The Funhouse album is a classic. Iggy probably got tired of doing that. He's been doing it since I've been doin' it. We were doing those kind of punk shows in 1967-'68. After a while you do get tired of eating peanut-butter and jelly, and you want to start cashing in on all this time you've put in on it. We rehearsed 12 hours a day sometimes — because we wanted to be challenging The Beatles on the charts."

When the band started making some money playing hard rock and small concerts, they earned enough to buy glitter and then props. In terms of audience identification, Alice invented glitter-rock. His so-called "freak-connection" — Wildman Fisher, Captain Beefheart, and, most important, Frank Zappa — was Alice's key to the recording industry. In those days, he was putting on a bizarre, quasi-dada stage show (which was used in-the 1970 film, Diary of a Mad Housewife). The band was better known for tearing up pillows and throwing feathers at the audience than for its music. By 1970 teenagers were looking for Alice's brand of apparently mindless insanity. The band was always big on straight-jackets; kids loved it. A lot of people were already getting bored of folkies-turned-rockers just getting up on stage and playing. They wanted something more — or, at least, something different. And Alice was ready to give it to them.

"Our running philosophy has always been give 'em something to talk about,'" Alice explains. "It's an old Barnum and Bailey and Ziegfeld kind of attitude. I think it still works in rock and roll. In the beginning they were still expecting a blond folk-singer, and when they got this kind of theater, they were going, 'Wow — what is this?!?!' Of course this was in '67, '68, '69 — everybody was into peace and flowers and love and everything like that, and we were into cars and drinking and girls."

Cars and drinking and girls ... and making it. Zappa and his manager, Herb Cohen, had a label at the time, called Straight Records. Straight it wasn't, and the label was perfect for Alice Cooper. The band produced its own first record, Pretties For You, which sounds as awful and pretentious today as it did in 1970. But what it did was set the tone for Alice Cooper's musical career: a good-time, fun band, the damn weirdest guys in town; a band brazenly flirting with dark and sinister forces and anything else considered beyond the pale for "normal" groups, always ready to go the distance for a low blow. It was a good reputation for a band trying to make an impact on public-consciousness. During one of Alice's tours, the Director of Youth Ministries for the United Methodist Church in Boston attacked Alice for building a show "on all that people fear — death, snakes, and changing sex roles."

"I never sat down and figured to do this and that," insists Alice. "Things are contrived, of course — our image and all — but it's contrived on the level of entertainment. It isn't contrived on any political level, nor, for selling anything. We aren't selling anything except entertainment. That's the only thing we care about. People will put a lot of moral value on what we do onstage — although the kids are smart enough not to."

Nope. No one can accuse Alice Cooper of trying to sell anything except himself and his creation. Rock and roll to him is as amoral as television — it's entertainment for its own sake (and for the sake of making money). In 1969, when bands like the Airplane and Dead were riding the crest of their popularity, Alice was already savvy to the hysterical dynamics that would later make Kiss the biggest American "music" group ever.

"We didn't have any blues influence. The music we remember are the TV theme songs like '77 Sunset Strip' and 'Bourbon Street Beat' — hip, cool stuff. We're products of the television age, the space age, and you can hear it in the music we play. We're not going to play Delta Blues. I don't give a damn about how many times his baby left him. We're upper middle-class suburban brats that had anything we wanted. We never had a blues period. We are living, breathing social criticism of the environment we grew up in."

When the original band — Glen Buxton (lead guitar), Michael Bruce (rhythm guitar, keyboards), Dennis Dunaway (bass), Neal Smith (drums), and, of course, Alice — moved from L.A. to Detroit, they had already made two crude records for Straight and had a reputation as the "worst band in Los Angeles," according to Alice. Love It to Death, still on Straight, was Cooper's first hit album. Largely due to producer Bob Ezrin's no-nonsense approach to work and to what Cooper calls the band's "desire to out-sell The Beatles," the album showed that the Alice Cooper Band had more going for it than just the theater of the absurd. The album made it into the Top Twenty and spurred two hit singles, "18" and "Caught in a Dream." Some people have credited the former with being America's answer to "My Generation" by The Who.

In 1971, the band had its first gold record, Killer, which included the hits "Under My Wheels" and "Be My Lover." By now they were rock giants, drawing huge audiences to their shows and gaining respect from music critics. When School's Out was released the following year, the band was at its peak. The album sold millions and made Alice Cooper an international star. Billion Dollar Babies and the subsequent tour, while very successful commercially, started a decline into self-parody and redundancy. Then in '74, Alice fired the band and hired Lou Reed's Rock'N Roll Animal backup band, led by Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter. It's important to remember that all the hits were written by the band and not just by Alice (Vince). In fact, Alice had no hand in writing the pair from Killer.

"I think," says Alice, "that the only reason the band broke up was because a lot of people at one point wanted to change the music, to leave the theatrics behind and prove that they could play, which was kind of silly. Just because we were getting all the press on the theatrics doesn't mean we couldn't play. We sold 40 million records because people liked the records — not the theatrics. But we always got reviews that the band was being smothered by the theater. I don't really believe that. I'd put them up against anybody. You couldn't ask for a better hard rock band. What you're really doing is giving the audience twice the show — by theatrics and music. I listen to our records and I'm really proud of 'em; I wouldn't put them out unless I was totally satisfied with them."

Today, the band is barely visible for a good deal of the show. The theatrics use the band as a kind of audio backdrop — an important one, but still not the main course. Retrospectively, it's easy to see that Alice was panting to "sell out," or, in Lester Bangs' words, "buy in," as soon as he could. Even his early albums, for all their crudeness and outrage, always had a touch of over-dramatic cabaret. When "Hello Hooray," a Judy Collins hit, came out by Alice, no one could deny where the boy was heading. The Welcome to My Nightmare show/LP (which was a television show and Atlantic Records soundtrack) was his first big bid for the Las Vegas trip. It was the Ice Capades. It was becoming very evident that Alice wanted nothing more than to become a fancy entertainer and part of the Vegas showroom tradition. His image became more and more involved with playing golf with aging stars, appearing on inane game shows, and making the Hollywood "scene."

"When I first came to Hollywood," he smiles, "I made a point of meeting people who weren't rockers, like Groucho and Fred Astaire — people that were old pros. And the amazing thing to me was that they understood what I was doing. Jack Benny and George Burns knew exactly what I was doing. George Burns said, 'You're a great kid, Alice, but that ain't new.' The best compliment I ever got was Groucho saying that the Alice Cooper show was the last of the great vaudevillian spectaculars. To me that was a great, great compliment."

So why not just go to Broadway?

"You can't make any money on Broadway, and what we're doing, in essence, is Broadway — only it's a traveling Broadway show," Alice asserts. "The only problem is that traveling is hard on the equipment, and you have to limit yourself a lot on special effects 'cause things that are intricate break easily. I believe in what we do, on an entertainment level. I think that when an audience leaves our show, they're thoroughly entertained. And that's why I'm still around, and that's why I can still go on tour after 15 years and pack any city in the country. And that's not bragging; it just means that I'm right about pure entertainment: it works."

Alice is what you might call a "trouper.'' Whereas Mick Jagger insists that he doesn't want to be still singing "Satisfaction" when he's 42, Alice definitely sees himself singing "School's Out" when he's 72.

"I have a different view of my work," he explains with all seriousness. "I enjoy it a lot. I can do it with the Alice Cooper image — on the level where it grows and gets more professional and so slick that by the time I'm 50 years old and you see the show, hard rock will be the music. It won't be like it's rebellious anymore. I don't know what teenagers will be doing to rebel then."

In 1975, Alice made his breakthrough and played at the Sahara Tahoe, one step away from Vegas. "It was just like going to hear Gilbert and Sullivan," wrote one critic disdainfully. You'd probably have to explain to Cooper that that is not a compliment.

But by then there was an element of eclipse creeping into Cooper's career. The times were passing him by and Alice's/Vince's personality was falling apart. And as that happened, he began drinking heavily and his career plummeted. It was then that Alice decided to commit himself to a sanatorium in upstate New York.

"I realized that I really didn't care about anything," he reflects. "I didn't care about performing anymore, I didn't care about recording, I didn't care about writing, I didn't care about golf; I didn't care about the way I dressed, the way I looked. I was in a total funk for about a year, and I still worked and hated working and hated everything about being onstage.

"After 13 years of working I hit, one year where I hated it, and that led to the drinking because the drinking relieved it. At least I was drunk enough to go through it. It was like an anesthetic. It sounds awful, but I think every performer will go through a period like that — where they just don't like it. I would've done anything! I would've sold shoes in Thom McAn's rather than go onstage. It was hard to explain that. But when your personality changes so drastically that nobody knows you, then you know that it's really wrong. I got sick of it. I was tired of being the brat that I was, I was tired of being this character that I hated. So I checked in and dedicated myself to getting rid of the main problem, which was the drinking.

"It's not a natural situation to be a 'star,'" he continues. "It's a very foreign thing to your spirit, your body — everything. It's so much fun, and at the same time it can be so destructive. You're playing a part all the time. A performer will be real secure in playing a part and hiding behind the part, and a lot of people won't see what's really tearing him up inside. You never want the audience to see what's really grinding at you, that you've got your problems, too. I wouldn't let anybody in. I locked everybody out of my problem. The only friend that I had was the bottle."

What compounded the drinking problem was that Alice started confusing the stage Alice with the real Alice (ex-Vince — whose wife, by the way, calls him "Alice"). "I kind of had the idea in my head that if I wasn't the character Alice all the time, the fans would be disappointed. I thought I had to be wearing black leather all the time and living in a big black castle. This psychiatrist said, 'Look at what happened: Alice got all the praise; Alice got all the reviews; Alice made all the money; Alice did everything, and you felt inadequate next to Alice. So this character got bigger than you. You have to remember, though, that you invented the character, so you're stronger than that character.'

"I had lost that thought, and the drinking helped me fog it over. And so I felt that I was always letting the audience down if I wasn't diabolical all the time. And I considered everyone the audience — even my wife, Cheryl. Finally, I got that thought out of my head and got to a reasonable thing where I said to myself, 'Look, you only have to be Alice 90 minutes a day, or if you're doing something that needs Alice, a TV thing or a movie. Now I look forward to being Alice onstage.

"It was a classic personality crisis. Jim Morrison had it, only he let himself get killed from it. He just lived the lifestyle. He believed his press, and he just always had to prove he was 'Jim Morrison, rebel.' I knew Jim pretty well, and he wasn't like that. But when he would see any sort of opportunity to get in the press on that level, he would do it. He wasn't that crazy; the guy was brilliant."

Alice's downhill slide is over now. And he tells the story about how he came back on his new album, From the Inside. He doesn't drink at all now. He's cured. "I thought I could not perform at all as Alice Cooper without being a little drunk, because I thought that was part of the Alice image, which is not true," he says. "Now it depends on my acting ability to play Alice. And that's even better for me, because that's a challenge and it's fun to do. Before, it was, 'Oh, whatever Alice does is going to be accepted anyway, so I'll just go up there and stumble around and be Alice.' Now I've really got to have control on the stage. And now I can be myself. Normally I'm a really up person, a really active person; I'm very rarely depressed."

Committing himself was a scary thing to do. It was a desperate measure for a desperate man. "You sign in, and then the doctors decide on when you can leave," says Alice, wide-eyed. "It's a New York state law that once you check in, it's up to the doctors' discretion if you are socially sane enough to leave. If they thought you were dangerous to yourself, they could keep you in, and I guess drinking the way I did was a slow suicide. I knew it was tearing me up inside. I told them I didn't want to leave the place until I never wanted to drink again. A lot of the therapy was just talking — just saying things to other people. I didn't get any special treatment, which I really liked. I liked being 'one of the guys.' The most important thing is saying things out loud that you thought you would never admit to anybody. Once you say, 'Yeah, I drink too much; I'm an alcoholic. I want to stop,' it becomes a reality, and then you can deal with it. And you're thinking with a clear head. You're not thinking with five or six whiskeys in you. You say it sober and you mean it."

Coincidentally, a neighbor of mine was a nurse at Alice's sanatorium. She told me that Alice was a model patient. He not only worked on his own problems but wound up helping everyone else, as well. It also inspired Alice. Let's face it — when you're starving on peanut-butter and jelly sandwiches, you've got a lot of openness for inspiration. But when you're a rich golfer from Benedict Canyon, and you've got so much of everything that you're not even inspired to ever leave your house, your work can begin to suffer. The stay in the sanatorium gave Alice the showman a whole new lease on life; his writing began to sparkle. The new album has a Tennesse Williams flare to it. It is his best effort in years.

He's working with most of Elton John's old band now, and writing with lyricist Bernie Taupin. Bernie, who is also Alice's closest friend, is a perfect writing partner for him. They both seem to be working for the same fusion of rock and cabaret.

Alice is 30 now, and he accepts that he's not 18 anymore. He's looking forward to maturing, as an artist as well as a personality; a body and a spirit. He expects to bring his audience with him. But he also admits that sometimes he feels like an aging gunslinger. He remembers wanting to go see a band of punk rockers at the Whisky last spring, but not going.

"A lot of times you'll get people who want to show off and get loud. They come over to your table and say, 'Hey, look who's here,' and you want to hit 'em, but you can't. I really don't like getting heavy with anybody. But at the same time, you get so many guys that are just total assholes who just want to use you. There's always that one guy that wants to take a poke at you just to say that he got in a fight with Alice. There's always some punk kid that thinks he's faster. I don't want any problems, but what I really want is to say, 'Step outside and I'll kick your fucking ass' — but I'd get sued. Everybody wants to be a star in L.A."

Well, it may have been his second try at it, but Alice has made it — he's a genuine L.A. star. He voted for Nixon. He did ads for the U.S. Army. He plays golf with Bob Hope and guests on Hollywood Squares. In fact, he can't imagine why President Ford once turned down an invitation to play golf with him. ("We're both University of Michigan fans: How could he be against me? I'm for everything that he's for. I stumble around onstage, too.") And he never killed any of those chickens onstage, either; that was all a lot of hype. He's even been denounced by Patti Smith as not deserving to be in rock and roll.

He's Alice Cooper, the All-American boy grown up. He knows he's after a long-term show business career, and he's willing to work for it and to change for it. Says Alice, "I don't want to go down in history as being some self-destructive idiot, or a self-destructive genius for that matter."

Photos: Jim Marshall