Article Database

Boston Globe

May 9, 1999

Magic that can set you free: rock 'n' roll's enduring power

Author: Jim Sullivan

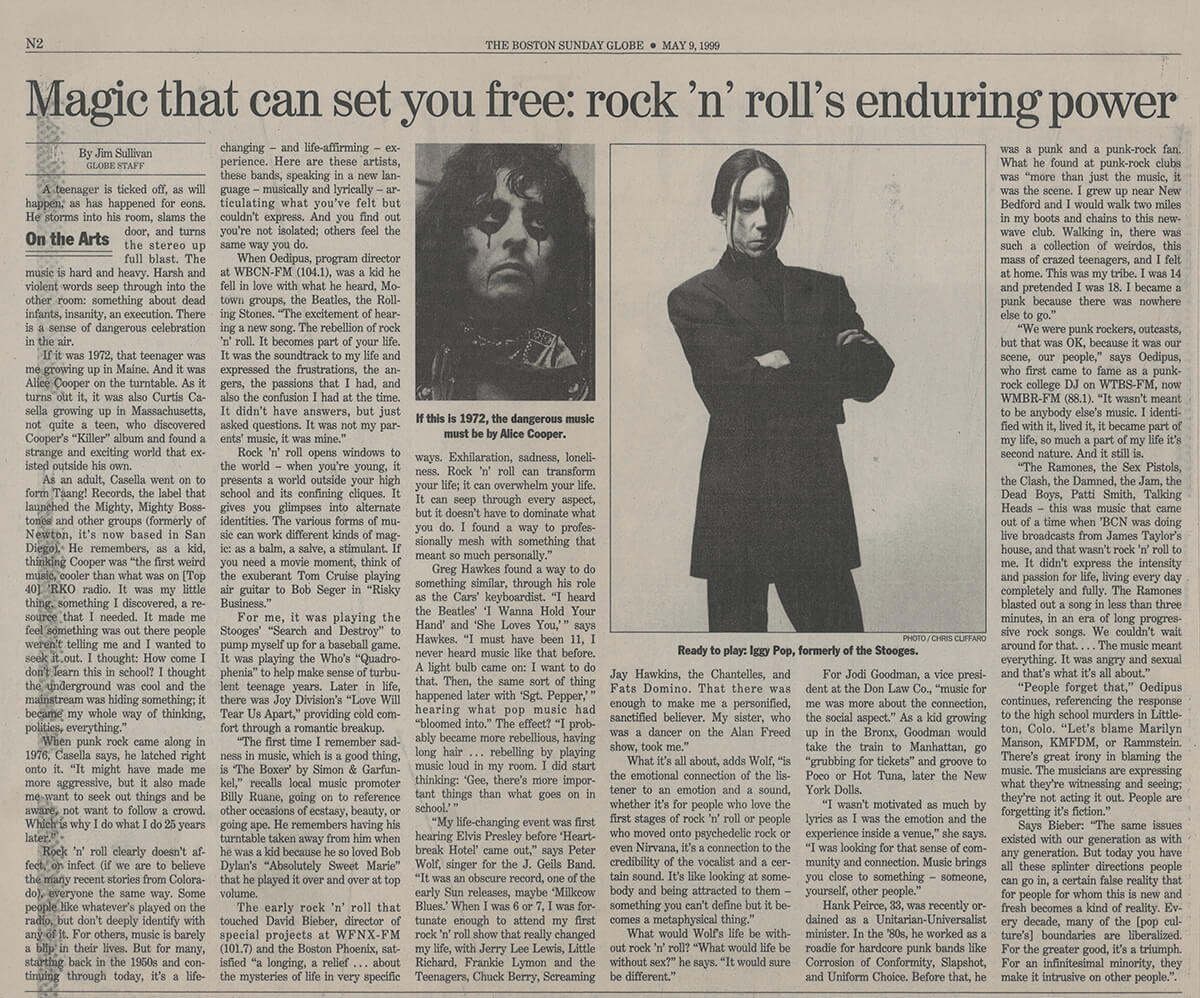

A teenager is ticked off, as will happen, as has happened for eons. He storms into his room, slams the door, and turns the stereo up full blast. The music is hard and heavy. Harsh and violent words seep through into the other room: something about dead infants, insanity, an execution. There is a sense of dangerous celebration in the air.

If it was 1972, that teenager was me growing up in Maine. And it was Alice Cooper on the turntable. As it turns out, it was also Curtis Casella growing up in Massachusetts, not quite a teen, who discovered Cooper's "Killer" album and found a strange and exciting world that existed outside his own.

As an adult, Casella went on to form Taang! Records, the label that launched the Mighty, Mighty Bosstones and other groups (formerly of Newton, it's now based in San Diego). He remembers, as a kid, thinking Cooper was "the first weird music, cooler than what was on [Top 40] 'RKO radio. It was my little thing, something I discovered, a resource that I needed. It made me feel something was out there people weren't telling me and I wanted to seek it out. I thought: How come I don't learn this in school? I thought the underground was cool and the politics, everything."

When punk rock came along in 1976, Casella says, he latched right onto it. "It might have made me more aggressive, but it also made me want to seek out things and be aware, not want to follow a crowd. Which is why I do what I do 25 years later."

Rock 'n' roll clearly doesn't affect, or infect (if we are to believe the many recent stories from Colorado), everyone the same way. Some people like whatever's played on the radio, but don't deeply identify with any of it. For others, music is barely a blip in their lives. But for many, starting back in the 1950s and continuing through today, it's a life-changing — and life-affirming — experience. Here are these artists, these bands, speaking in a new language — musically and lyrically — articulating what you've felt but couldn't express. And you find out you're not isolated; others feel the same way you do.

When Oedipus, program director at WBCN-FM (104.1), was a kid he fell in love with what he heard, Motown groups, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones. "The excitement of hearing a new song. The rebellion of rock 'n' roll. It becomes part of your life. It was the soundtrack to my life and expressed the frustrations, the angers, the passions that I had, and also the confusion I had at the time. It didn't have answers, but just asked questions. It was not my parents' music, it was mine."

Rock 'n' roll opens windows to the world — when you're young, it presents a world outside your high school and its confining cliques. It gives you glimpses into alternate identities. The various forms of music can work different kinds of magic: as a balm, a salve, a stimulant. If you need a movie moment, think of the exuberant Tom Cruise playing air guitar to Bob Seger in "Risky Business."

For me, it was playing the Stooges' "Search and Destroy" to pump myself up for a baseball game. It was playing the Who's "Quadrophenia" to help make sense of turbulent teenage years. Later in life, there was Joy Division's "Love Will Tear Us Apart," providing cold comfort through a romantic breakup.

"The first time I remember sadness in music, which is a good thing, is 'The Boxer' by Simon & Garfunkel," recalls local music promoter Billy Ruane, going on to reference other occasions of ecstasy, beauty, or going ape. He remembers having his turntable taken away from him when he was a kid because he so loved Bob Dylan's "Absolutely Sweet Marie" that he played it over and over at top volume.

The early rock 'n' roll that touched David Bieber, director of special projects at WFNX-FM (101.7) and the Boston Phoenix, satisfied "a longing, a relief... about the mysteries of life in very specific ways. Exhilaration, sadness, loneliness. Rock 'n' roll can transform your life; it can overwhelm your life. It can seep through every aspect, but it doesn't have to dominate what you do. I found a way to professionally mesh with something that meant so much personally."

Greg Hawkes found a way to do something similar, through his role as the Cars' keyboardist. "I heard the Beatles' 'I Wanna Hold Your Hand' and 'She Loves You,'" says Hawkes. "I must have been 11, I never heard music like that before. A light bulb came on: I want to do that. Then, the same sort of thing happened later with 'Sgt. Pepper,'" hearing what pop music had "bloomed into." The effect? "I probably became more rebellious, having long hair... rebelling by playing music loud in my room. I did start thinking: 'Gee, there's more important things than what goes on in school.'"

"My life-changing event was first hearing Elvis Presley before 'Heartbreak Hotel' came out," says Peter Wolf, singer for the J. Geils Band. "It was an obscure record, one of the early Sun releases, maybe 'Milkcow Blues.' When I was 6 or 7, I was fortunate enough to attend my first rock 'n' roll show that really changed my life, with Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, Chuck Berry, Screaming Jay Hawkins, the Chantelles, and Fats Domino. That there was enough to make me a personified, sanctified believer. My sister, who was a dancer on the Alan Freed show, took me."

What it's all about, adds Wolf, "is the emotional connection of the listener to an emotion and a sound, whether it's for people who love the first stages of rock 'n' roll or people who moved onto psychedelic rock or even Nirvana, it's a connection to the credibility of the vocalist and a certain sound. It's like looking at somebody and being attracted to them — something you can't define but it becomes a metaphysical thing."

What would Wolfs life be without rock 'n' roll? "What would life be without sex?" he says. "It would sure be different."

For Jodi Goodman, a vice president at the Don Law Co., "music for me was more about the connection, the social aspect." As a kid growing up in the Bronx, Goodman would take the train to Manhattan, go "grubbing for tickets" and groove to Poco or Hot Tuna, later the New York Dolls.

"I wasn't motivated as much by lyrics as I was the emotion and the experience inside a venue," she says. "I was looking for that sense of community and connection. Music brings you close to something — someone, yourself, other people."

Hank Peirce, 33, was recently ordained as a Unitarian-Universalist minister. In the '80s, he worked as a roadie for hardcore punk bands like Corrosion of Conformity, Slapshot, and Uniform Choice. Before that, he was a punk and a punk-rock fan. What he found at punk-rock clubs was "more than just the music, it was the scene. I grew up near New Bedford and I would walk two miles in my boots and chains to this newwave club. Walking in, there was such a collection of weirdos, this mass of crazed teenagers, and I felt at home. This was my tribe. I was 14 and pretended I was 18. I became a punk because there was nowhere else to go."

"We were punk rockers, outcasts, but that was OK, because it was our scene, our people," says Oedipus, who first came to fame as a punk rock college DJ on WTBS-FM, now WMBR-FM (88.1). "It wasn't meant to be anybody else's music. I identified with it, lived it, it became part of my life, so much a part of my life it's second nature. And it still is.

"The Ramones, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Damned, the Jam, the Dead Boys, Patti Smith, Talking Heads — this was music that came out of a time when 'BCN was doing live broadcasts from James Taylor's house, and that wasn't rock 'n' roll to me. It didn't express the intensity and passion for life, living every day completely and fully. The Ramones blasted out a song in less than three minutes, in an era of long progressive rock songs. We couldn't wait around for that.... The music meant everything. It was angry and sexual and that's what it's all about."

"People forget that," Oedipus continues, referencing the response to the high school murders in Littleton, Colo. "Let's blame Marilyn Manson, KMFDM, or Rammstein. There's great irony in blaming the music. The musicians are expressing what they're witnessing and seeing; they're not acting it out. People are forgetting it's fiction."

Says Bieber: "The same issues existed with our generation as with any generation. But today you have all these splinter directions people can go in, a certain false reality that for people for whom this is new and fresh becomes a kind of reality. Every decade, many of the [pop culture's] boundaries are liberalized. For the greater good, it's a triumph. For an infinitesimal minority, they make it intrusive on other people."