Article Database

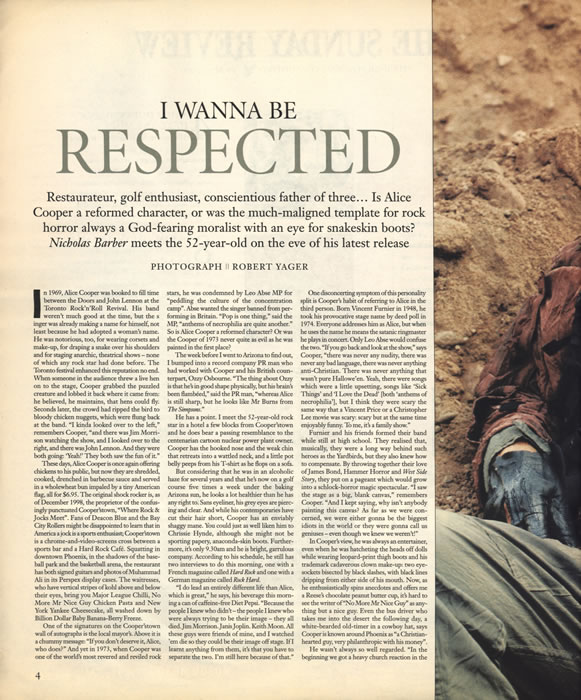

I Wanna Be Respected

Restaurateur, golf enthusiast, conscientious father of three . . . Is Alice Cooper a reformed character, or was the much-maligned template for rock horror always a God-fearing moralist with an eye for snakeskin boots? Nicholas Barber meets the 52-year-old

In 1969, Alice Cooper was booked to fill time between the Door and John Lennon at the Toronto Rock 'n' Roll Revival. His band weren't much good at the time, but the singer was already making a name for himself, not least because he has adopted a woman's name. He was notorious, too, for wearing corsets and make-up, for draping a snake over his shoulders and for staging anarchic, theatrical shows – none of which any rock star had done before. The Toronto festival enhanced this reputation no end. When someone in the audience threw a live hen on to the stage, Cooper grabbed the puzzled creature and lobbed it back where it came from" he believed, he maintains, that hens could fly. Seconds later, the crowd had ripped the bird to bloody chicken nuggets, which were flung back at the band. "I kinda looked over to the left," remembers Cooper, "and there was Jim Morrison watching the show, and I looked over to the right, and there was John Lennon. And they were both going: 'Yeah!' they both saw the fun of it."

These days, Alice Cooper is once again offering chickens to his public, but now they are shredded, cooked, drenched in barbecue sauce and served in a wholewheat bun impaled by a tiny American flag, all for $6.95. The original shock rocker is, as of December 1998, the proprietor of the confusing punctuated Cooper'sTown, "Where Rock & Jocks Meet". Fans of Deacon Blue and the Bay City Rollers might be disappointed to learn that in America a jock is a sports enthusiast; Cooper'sTown is a chrome-and-video-screens cross between a sports bar and a Hard Rock Café. Squatting in downtown Phoenix, in the shadows of the baseball park and the basketball arena, the restaurant has both signed guitars and photos of Muhammad Ali in its Perspex display cases. The waitresses, who have vertical stripes of kohl above and below their eyes, bring you Major League Chilli, No More Mr Nice Guy Chicken Pasta and New York Yankee Cheesecake, all washed down by Billion Dollar Baby Banana-Berry Freeze.

One of the signatures on the Cooper'sTown wall of autographs is the local mayor's. Above it is a chummy message: "If you don't deserve it, Alice, who does?" And yet in 1973, when Cooper was one of the world's most revered and reviled rock stars, he was condemned by Leo Abse MP for "peddling the culture of the concentration camp". Abse wanted the singer banned from performing in Britain. "Pop is one thing," said the MP, "anthems of necrophilia are quite another." So is Alice Cooper a reformed character? Or was the Cooper of 1973 never quite as evil as he was painted in the first place? The week before I went to Arizona to find out, I bumped into a record company PR man who had worked with Cooper and his British counterpart, Ozzy Osbourne. "The thing about Ozzy is that he's in good shape physically, buthis brain's been flambéed," said the PR man, "whereas Alice is still sharp, but he looks like Mr Burns from The Simpsons."

He has a point. I meet the 52-year-old rock star in a hotel a few blocks from Cooper'sTown and he does bear a passing resemblance to the centenarian cartoon nuclear power plant owner. Cooper has the hooked nose and the weak chin that retreats into a wattled neck, and a little pot belly peeps from his T-shirt as be flops on the sofa.

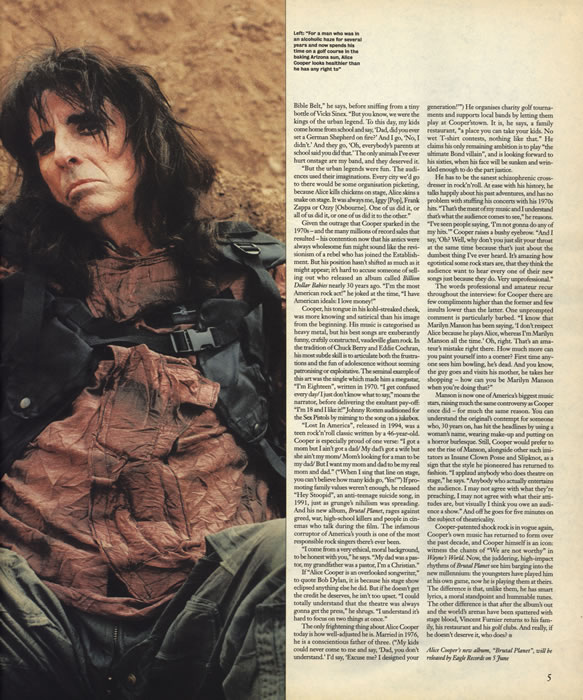

But considering that he was in an alcoholic haze for several years and that he's now on a golf course five times a week under the baking Arizona sun, he looks a lot healthier than he has any right too. Sans eyeliner, his grey eyes are piercing and clear. And while his contemporaries have cut their hair short, Cooper has an enviably shaggy mane. You could just as well liken him to Chrissie Hynde, although she might not be sporting papery, anaconda-skin boos. Furthermore, it's only 9:30am and he is bright, garrulous company. According to his schedule, he still has two interviews to do this morning, one with a French magazine called Hard Rock and one with a German magazine called Hard Rock.

"I do lead an entirely different life than Alice, which is great," he says, his beverage this morning a can of caffeine-free Diet Pepsi. "Because the people I knew who didn't – the people I know who were always trying to be their image – they all died. Jim Morrison. Janis Joplin. Keith Moon. All these guys were friends of mine, and I watched 'em die so they could be their image off stage. If I learnt anything from them, it's that you have to separate the two. I'm still here because of that."

One disconcerting symptom of his personality split is Cooper's habit of referring to Alice in the third person. Born Vincent Furnier in 1948, he took his provocative stage name by deed poll in 1974. Everyone addresses him as Alice, but when he uses the name he means the satanic ringmaster he plays in concert. Only Leo Abse would confuse the two. "If you go back and look at the show," says Cooper, "there was never any nudity, there was never any bad language, there was never anything anti-Christian. There was never anything that wasn't pure Hallowe'en. Yeah, there were songs which were a little upsetting, songs like 'Sick Things' and 'I Love The Dead' [both 'anthems of necrophilia'], but I think they were scary the same way that a Vincent Price or a Christopher Lee movie was scary: scary but at the same time enjoyably funny. To me, it's a family show."

Furnier and his friends formed their band while still at high school. They realized that, musically, they were a long way behind such heroes as the Yardbirds, but they also knew how to compensate. By throwing together their love of James Bond, Hammer Horror and West Side Story, they put on a pageant which would grow into a schlock-horror magic spectacular. "I saw the stage as a big, blank canvas," remembers Cooper. "And I kept saying, why isn't anybody painting this canvas? As far as we were concerned, we were either gonna be the biggest idiots in the world or they were gonna call us geniuses – even though we knew we weren't!"

In Cooper's view, he was always an entertainer, even when he was hatcheting the heads off dolls while wearing leopard-print thigh boots and his trademark cadaverous clown make-up: two eye-sockets bisected by black slashes, with black lines dripping from either side of the mouth. No, as he enthusiastically spins anecdotes and offers me a Reese's chocolate peanut butter cup, it's hard to see the writer of "No More Mr Nice Guy" as anything but a nice guy. Even the bus driver who takes me into the desert the following day, a white-bearded old-timer in a cowboy hat, says Cooper is known around Phoenix as "a Christian-hearted guy, very philanthropic with his money."

He wasn't always so well regarded. "In the beginning we got a heavy church reaction in the Bible belt," he says, before sniffing from a tiny bottle of Vicks Sinex. "But you know, we were the kings of the urban legend. To this day, my kids come home from school and say, 'Dad, did you ever set a German Shepherd of fire?' And I go, 'No, I didn't' And they go, 'Oh, everybody's parents at school said you did that.' The only animals I've ever hurt onstage are my band, and they deserve it.

"But the urban legends are fun. The audiences used their imaginations. Every city we'd go to there would be some organization picketing, because Alice kills chickens onstage, Alice skins a snake on stage. It was always me, Iggy [pop], Frank Zappa or Ozzy [Osbourne]. One of us did it, or all of us did it, or one of us did it to the other."

Given the outrage that Cooper sparked in the 1970s – and the many millions of record sales that resulted – his contention now that his antics were always wholesome fun might sound like the revisionism of a rebel who has joined the Establishment. But his position hasn't shifted as much as it might appear; it's hard to accuse someone of selling out who released an album called Billion Dollar Babies nearly 30 years ago. "I'm the most American rock act!" he joked at the time, "I have American ideals: I love money!"

Cooper, his tongue in his kohl-streaked cheek, was more knowing and satirical than his image from the beginning. His music is categorized as heavy metal, but his best songs are exuberantly funny, craftily constructed, vaudeville glam rock. In the tradition of Chuck Berry and Eddie Cochran, his subtle skill is to articulate both the frustrations and the fun of adolescence without seeming patronizing or exploitative. The seminal example of this art was the single which made him a megastar, "I'm Eighteen", written in 1970. "I get confused every day/I just don't know what to say," moans the narrator, before delivering the exultant pay-off: "I'm 18 and I like it!" Johnny Rotten auditioned for the Sex Pistols by miming to the song on a jukebox.

"Lost In America", released in 1994, was a teen rock 'n' roll classic written by a 46-year-old. Cooper is especially proud of one verse: "I got a mom but I ain't got a dad/My day's got a wife but she ain't my mom/Mom's looking for a man to be my dad/But I want my mom and dad to be my real mom and dad." ("When I sing that line on stage, you can't believe how many kids go, 'Yes!'") If promoting family values weren't enough, he released "Hey Stoopid", an anti-teenage suicide song, in 1991, just as grunge's nihilism was spreading. And his new album, Brutal Planet, rages against greed, war, high-school killer and the people in cinemas who talk during the film. The infamous corruptor of America's youth is one of the most responsible rock singers there's ever been.

"I come from a very ethical, moral background, to be honest with you," he says, "My dad was a pastor, my grandfather was a paster, I'm a Christian."

If "Alice Cooper is an overlooked songwriter," to quote Bob Dylan, it is because his stage show eclipsed anything else he did. But if he doesn't get the credit he deserves, he isn't too upset. "I could totally understand that the theatre was always gonna get the press," he shrugs. "I understand it's hard to focus on the two things at once."

The only frightening thing about Alice Cooper today is how well-adjusted he is. Married in 1976, he is a conscientious father of three. ("My kids could never come to me and say, 'Dad, you don't understand." I'd say, 'Excuse me? I designed you generation!") He organizes charity golf tournaments and supports local bands by letting them play at Cooper'stown. It is, he says, a family restaurant, "a place you can take you kids. No wet T-shirt contest, nothing like that." He claims his only remaining ambition it to play "the ultimate Bond villain", and is looking forward to the sixties, when his face will be sunken and wrinkled enough to do the part justice.

He has to be the sanest schizophrenic cross-dresser in rock 'n' roll. At east with his history, he talks happily about his past adventures, and has no problem with stuffing his concerts with his 1970s hits. "That's the meat of my music and I understand that's what the audience comes to see," he reasons. "I've seen people saying, 'I'm not gonna do any of my hits.'" Cooper raises a bushy eyebrow. "And I say, 'Oh? Well, why don't you just slit your throat at the same time because that's just about the dumbest thing I've ever heard. It's amazing how egotistical some rock stars are, that they think the audience want to hear every one of their new songs just because they do. Very unprofessional."

The words professional and amateur recur through the interview: for Cooper there are few compliments higher than the former and few insults lower than the latter. One unprompted comment is particularly barbed. "I know that Marilyn Manson has been saying, 'I don't respect Alice because he plays Alice, whereas I'm Marilyn Manson all the time.' Oh, right. That's an amateur's mistake right there. How much more can you paint yourself into a corner? First time anyone sees him bowling, he's dead. And you know, the guy goes and visits his mother, he takes her shopping – how can you be Marilyn Mason when you're doing this?"

Manson is now one of America's biggest music stars, raising much the same controversy as Cooper once did – for much the same reason. You can understand the original's contempt for someone who, 30 years on, has hit the headlines by using a woman's name, wearing make-up and putting on a horror burlesque. Still, Cooper would prefer to see the rise of Manson, alongside other such imitators as Insane Clown Posse and Slipknot, as a sign that the style he pioneered has returned to fashion. "I applaud anybody who does theatre on stage," he says. "Anybody who actually entertains the audience. I may not agree with what they're preaching, I may not agree with what their attitudes are, but visually I think you own an audience a show." And off he goes for five minutes on the subject of theatricality.

Cooper-patented shock rock is in vogue again, Cooper's own music has returned to form over the past decade, and Cooper himself is an icon: witness the chants of "We are not worthy" in Wayne's World. No, the juddering, high-impact rhythms of Brutal Planet see him barging into the new millennium: the youngsters have played him at his own game, now he is play them at theirs. The difference is that, unlike them, he has smart lyrics, a moral standpoint and hummable tunes. The other difference is that after the album's out and the world's arenas have been splattered with stage blood, Vincent Furnier returns to his family, his restaurant and his golf clubs. And really, if he doesn't deserve it, who does?

Alice Cooper's new album, "Brutal Planet", wil lbe released by Eagle Records on 5 June.

(Published in The Independent on Sunday in the Sunday Review supplement on 14th May 2000)