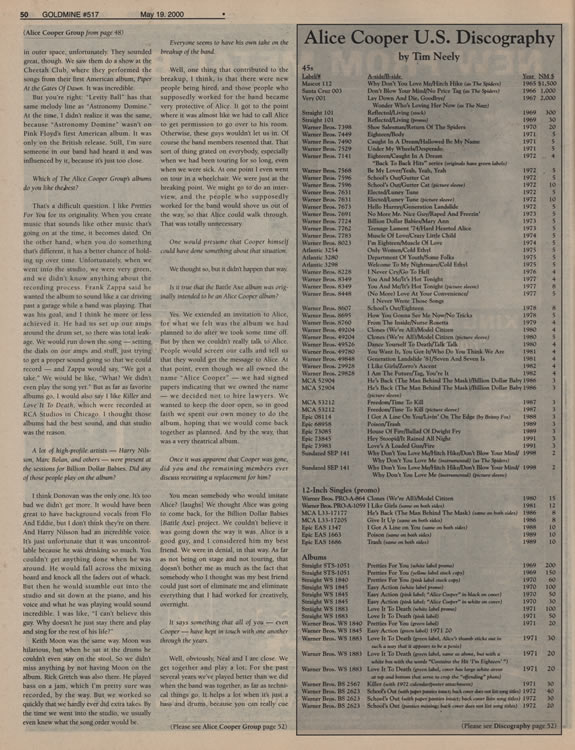

Article Database

Alice Cooper - From The Inside

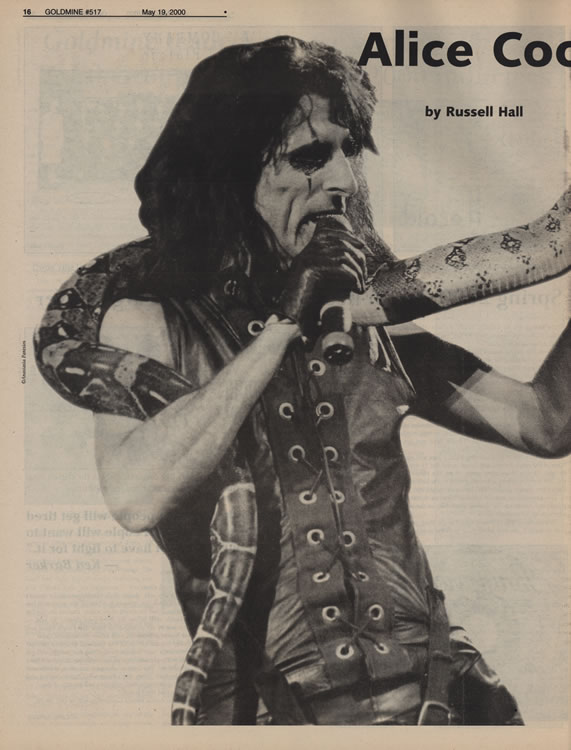

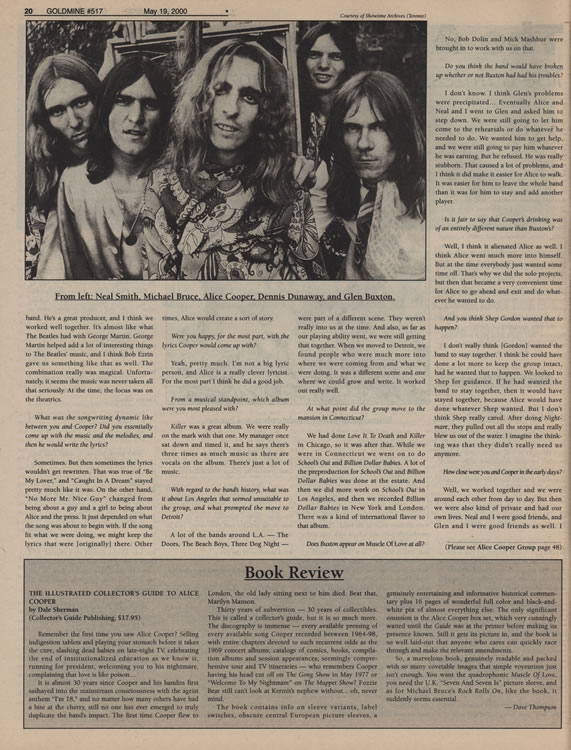

Back in the early '70s when The Alice Cooper Group resided high atop the record charts, few would have predicted that the band's mascaraed lead singer would sustain on of rock 'n' rolls most successful careers. Thirty years later, however, what was once thought to be a passing fad is now an American institution. The son of the Baptist minister, Cooper and several of his teenage classmates founded their first band as a lark for the high school talent show. First called the Earwigs, then The Spiders, then The Nazz, the group eventually settled on the name Alice Cooper. By then (1968), the band had settled into a lineup that featured - in addition to Cooper - Michael Bruce (guitar), Glen Buxton (guitar), Dennis Dunaway (bass), and Neal Smith (drums).

After recording two albums that centered on abstract psychedelic pop, the group tightened its musical act with the release of 1971's Love It To Death. Under the direction of producer Bob Ezrin, the album proved to be the first of several releases that couched macabre themes and sexual ambivalence in searing rock 'n' roll. Over the course of the next three albums - Killer, School's Out and Billion Dollar Babies - The Alice Cooper Group ruled both the charts and the airwaves. Helping fuel the flames of their popularity was the band's notorious stage act, which at various times included beheadings, mutilated dolls and hangings.

Since leaving the group in 1975, Alice Cooper as a solo artist has released albums that have ranged from spotty (Dada, Special Forces) to the excellent (Welcome To My Nightmare, Trash). Throughout the '90s, Cooper's career has been on a steady musical upswing, as evidence by 1994's stellar The Last Temptation and the 1995 live album A Fistful of Alice. In addition, in the summer of 1999 Rhino Records issued a four-disc box set, The Life And Crimes of Alice Cooper, which offers a glorious assessment of a body of work that stretches across more than 25 albums. Tentatively scheduled for June release on Spitfire Records is Brutal Planet, which is being billed by the heavy metal label as Cooper's "most belligerent yet."

Let's talk about the Rhino box set a bit. Were there any songs that you specifically asked to be included or excluded?

I only asked for one song to be excluded, and that was "(No More) Love At Your Convenience." That song was our pathetic attempt to make fun at disco. At the last moment I thought: "You know, people are going to think we're actually serious. I don't want to take the chance that they won't understand that this is satire." It's like when I did Hollywood Squares. I thought everyone would get the joke and realize that I didn't really belong on that show. When I did a disco song, I thought everyone would get the joke of understand that I hate disco. But then I began to think, "They didn't understand the Hollywood Squares thing. Why would they get this?" On the other hand, I absolutely insisted that "Serious," from the album From the Inside, be included, as well as "Man With The Golden Gun," "Tag, You're It," "Former Lee Warmer".

One song that really comes over surprisingly well is the cover of Jimi Hendrix's "Fire."

That came out of a rehearsal in Woodstock. Somebody just started playing [mimics the song's opening riff], with the exact tone Hendrix had used. I was like, "Do you know that?" It turned out everybody knew it, and I felt like I could fake the lyrics, so I suggested we run it through. We did it three times, and the third take turned out really good. You know, Jimi Hendrix was the guy who basically hooked [longtime Cooper manager] Shep Gordon together with the band. Hendrix knew we were living in The Chamber Brothers' basement, and he knew Shep was looking to manage a rock group. He told Shep we were basically living in a basement in Watts, that we needed a manager and that we were going to sign with Frank Zappa. Shep was like, "OK, I'll manage 'em." And he and I have been together for 30 years now.

After you got your hands on the complete box set, did you ever listen to it from start to finish?

I did, yeah. I listened to the whole thing during a really long drive from [Arizona] to northern California.

What sort of feelings did you have?

Well, I have to be honest with you, I'm not very nostalgic about my music, although that may change [later]. When I'm about 70 years old I'll probably look back and think, "Ah, yes, I remember that." But right now, I'm still at the point where I sort of look at songs on the box set and think, "Gee, which of these would be good for the stage?" For me, they're all still working pieces. It's not about nostalgia. It was more a case of, "Well, it's about time we compiled these songs together." But for people who are nostalgic, yeah, it might take them back to when they got their first car or when they went to their first concert.

None of these songs conjure up specific memories for you?

Oh yes, of course. It's just I don't dwell on it. It's more likely that I'll listen to something like "Don't Blow Your Mind" or "Nobody Likes Me" and think, "Gee, I wonder what that would sound like with my new band now." A song my pique my interest in that way.

Did anyone express reservations about including the Battle Axe song?

No, not at all. The guys in the [original Alice Cooper] band and I are still friends. In fact, we did a thing at Cooperstown - my restaurant - where Neal [Smith] and Mike [Bruce] showed up and we did 35 minutes on stage. We're still friends and everything. I don't think there was ever any bitterness.

Did the other original members have much input into the box set?

No, that was pretty much done by [Cooper's personal assistant] Brian [Nelson], because I wanted it done from a fan's point of view. If it had been left to me, I probably would've picked some pretty odd-sounding stuff. It really wouldn't have represented each album the way it does now. But of course the other guys - and Bob Ezrin as well - contributed those great track-by-track comments in the liner notes. It's hard to look back any time after the breakup and see any bitter period with anybody. Even when Mike was writing his book and hashing through various things, I was laughing more than I was angry. People would ask me about the book, and I would tell them I thought it was one the great works of fiction from the 20th century. It's right up there with [Cooper's 1975 autobiography] Me, Alice. At this point the true story of the Alice Cooper group hasn't been written.

Speaking of which, what did you think of the Billion Dollar Baby book written by Bob Greene all those years ago?

Well, it was written from the point of view of somebody who came on tour and observed. That was probably closer to the truth, because it involved someone giving an objective point of view about what he saw. But even then, once we found Bob was gullible, we started padding things a bit. In other words, I might say, "OK, Neal, when we go into the hotel room, make sure you throw an ashtray at me. I'll duck, and then I'll throw a beer can at you. " We juiced up a few things without telling Bob, and then when he would leave we would have a good laugh.

But that was a good book. At one time Sylvester Stallone owned the rights to it, and he was going to make a movie from it. He wanted to play Shep. It was on the best-seller's list, so I'm sure it was one of those things where [Stallone] looked down the list and thought, "Well, this is an interesting property." I almost did the same thing when Interview With The Vampire came out. Bernie Taupin and I put a bid to buy the right to it, but somebody had already bought it for something like $300,000. We figured we could pick it up for $500,000 or so. Of course the movie didn't get made until 20 years later. I was thinking Peter O'Tool would make a great Lestat.

Returning to the box set: One thing that comes across is that the material from The Last Temptation is really strong.

That's one of my favorites. As far as having an emotional impact goes, I thought that record ranked among the best of the Alice albums. It had a really strong "rock" feel to it as well. But I also think that if you go back and listen to disc one, two, three and four in order, you can hear the progression in writing and in the production. You can tell where the high points and the low points were. When I was really having problems with alcohol, you can detect that in the material. Although I think the material held up lyrically, and musically it was still good, I felt there was no energy in the production. That was true with Flush The Fashion, Zipper Catches Skin, Dada, and probably Special Forces. With those four albums, I felt there was a real lack of energy, even though when I listen to them I don't have any problem with the songs.

During the time you were drinking, were you cognizant of the fact the work was suffering?

Oh, yeah, I was. I just wasn't brave enough to check myself into a hospital. But it was also at a time when rock 'n' roll wasn't a big deal on the radio. I knew that I had to make records just to keep my name in the game - and I was making rock 'n' roll albums that I believed in - but I also knew I wasn't going to get any radio play because of disco. If rock 'n' roll was going to get played on the radio at all, it was going to be a Rolling Stones song or a Led Zeppelin song. Alice Cooper and other rock 'n' roll bands weren't going to get played, and we basically understood that. Rock wasn't what people wanted to hear at that point, so radio would pick up the ballad. Every album that I would put out would have a ballad on it, and those would end up being the hits.

Were some of the albums more fun to make than others?

Some of them were, and then some of them were really hard work. Love It To Death was a hard, hard album to make. Bob Ezrin just beat us to death on that one. All the really big albums were difficult, because Bob was so anal about everything. But that's also why they ended up being so huge. For me, one of the fun records was From The Inside, which also ended up being one of my favorite musical albums. And Alice Cooper Goes To Hell was fun to make because everybody contributed and everybody was having a great time with the idea of Alice trying to talk his way out of hell. Welcome To My Nightmare was fun, too.

There was so much riding on the success of Welcome To My Nightmare, did you have any sort of contingency plan in place, on the chance it didn't succeed?

No, we just rolled the dice. Shep asked how much money I had, and I told him he knew [the answer to that] better than I did. It turned out I had about $400,000 and he had about $400,000, so we put all that into the project. Our thinking was, "If it works, it works, and if it doesn't, then we'll start all over." I was thinking, "What happens if we get out there and everybody says, 'Without the band, we don't want to know about Alice Cooper?'" We did everything we could to make sure it would be either the biggest success - or the biggest failure - we ever had.

Back in the early days, there seemed to be a giant leap in the strength of the songwriting between Easy Action and Love It To Death.

For me, Pretties For You and Easy Action were really Nazz albums. Basically it was The Nazz - our original band - that was responsible for those albums. When Bob Ezrin came along, we stopped doing everything else and just started writing and invented Alice Cooper basically in the barn, there in Detroit. I really consider Love It To Death to be the first Alice Cooper album. Other people will argue with me about that, but I would say that was the first time everything gelled or had a singular feel. But, having said that, I'm not ashamed of those first two albums. Frank Zappa listened to Pretties For You and said he wouldn't know how to write this stuff for The Mothers [of Invention]. He pointed out that the time changes didn't make any sense at al, which was why he liked it so much. I thought that was a great compliment.

In a lot of ways those first two albums seem more contemporary today than they did at the time they were made.

Oh, yeah. If Pretties For You came out right now and it was produced properly, people would think, "Finally, something new!" "No Longer Umpire," "B.B. On Mars," "10 Minutes Before The Worm".where was that stuff coming from? If those songs came out now and I heard them on the radio, I would be elated. I'd buy that album in a second, because it's so different. I'm surprised some of the alternative bands haven't picked up on the really early Alice stuff and redone some of it.

To what extent was Ezrin responsible for the chemistry of the band?

Well, Bob Ezrin was our George Martin. When he first came to see us play, he saw that the audience went crazy. But he also saw that what stirred people up wasn't the music - it was our attitude and showmanship. He pointed out that we hadn't yet written a classic "Alice" song. And then, when we wrote [the songs for] Love It To Death suddenly we had about nine of them. "Ballad Of Dwight Fry" is probably the quintessential Alice Cooper song. I was actually in a straight-jacket while we recorded it. Bob piled some folded chairs on top of me, so that I would be covered in about 50 pounds of weight. It was just ridiculous, but we did all kinds of things like that.

It was interesting that your high school track coach was featured in the VH-1 biography. Do you make a special effort to keep in contact with people from your childhood?

Oh, absolutely. I see friends of mine from those days all the time. My track coach was a really good guy. He was a Mormon "elder," and he didn't like coffee, Coca-Cola, or dancing but somehow he really got sucked up into The Earwigs. That track team went 72 and 0, and three of the guys in the band were the top milers in the state. I was running, like, 4:30 miles and Dennis was around 4:26 and [original Earwigs drummer] John Speer was better than both of us. That was the weird thing. People would come to our shows and go, "Hey, those guys just got medals in the state track meet last week. What are they doing in this weird band?"

The original Alice Cooper band meets all the qualifications necessary to be in The Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. Do you have any thoughts about that?

I don't know. I mean, we have every credential there ever was. We sold as many records as anybody who's ever been in there, and we have certainly influenced enough people. My thinking is, I would really hate for all my props to make the Hall Of Fame, but not me. The props - the guillotine and so forth - are already in the Hall Of Fame. And I can't imagine them putting Kiss, or somebody like that, before Alice Cooper. That would sort of nullify the whole thing. That would be like putting The Dave Clark Five in before The Beatles.

Are you pleased that the box set renewed so much interest in the original Alice Cooper Band, or do you sometimes get weary of talking about those years?

Well, it happened, and we were part of American history. If we had just been a band that was kind of there, who kind of rode the wave, that would be one thing. But the Alice Cooper Band actually changed the way people looked when they walked down the street. And we changed the way stage shows look. We had a big impact on the entire culture, and it wasn't just the music, although the music has stood up well over all these years. I think we were at the apex of a movement, although at the time we didn't know we were having that much impact. For us, it was just a matter of having fun.

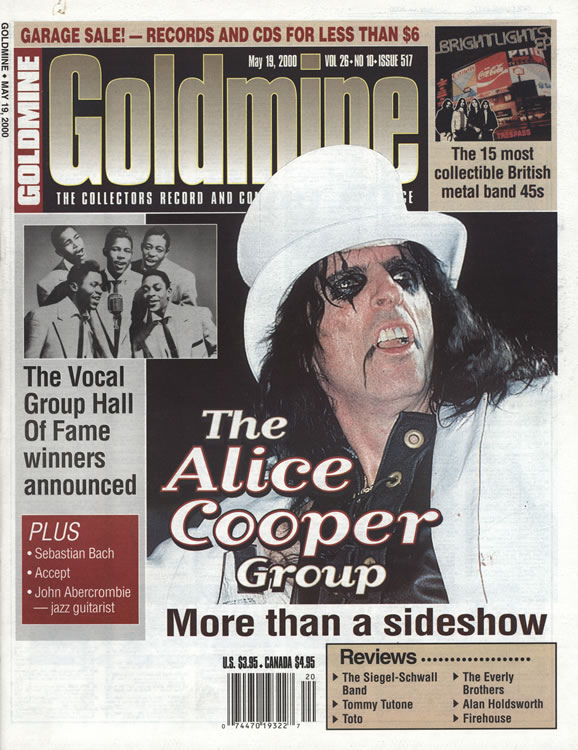

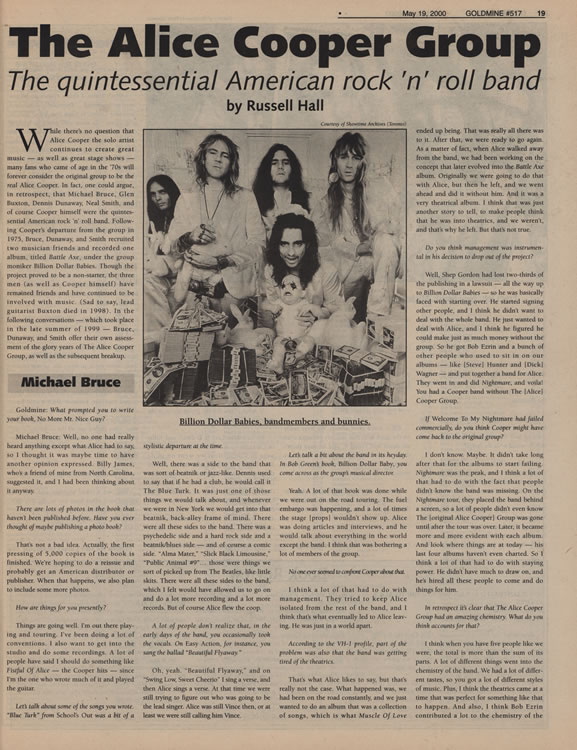

The Alice Cooper Group

The quintessential American rock 'n' roll band

While there's no question that Alice Cooper the solo artist continues to create great music - as well as great stage shows - many fans who came of age in the '70s will forever consider the original group to be the real Alice Cooper. In fact, one could argue, in retrospect, that Michael Bruce, Glen Buxton, Dennis Dunaway, Neal Smith, and of course Cooper himself were the quintessential American rock 'n' roll band. Following Cooper's departure from the group in 1975, Bruce, Dunaway, and Smith recruited two musician friends and recorded one album, titled Battle Axe, under the group moniker Billion Dollar Babies. Though the project proved to be a non-starter, the three men (as well as Cooper himself) have remained friends and have continued to be involved with music. (Sad to say, lead guitarist Buxton died in 1998). In the following conversations - which took place in the late summer of 1999 - Bruce, Dunaway, and Smith offer their own assessment of the glory years of The Alice Cooper group, as well as the subsequent breakup.

Michael Bruce

What prompted you to write your book, No More Mr. Nice Guy?

Well, no one had really heard anything except what Alice had to say, so I thought it was maybe time to have another opinion expressed. Billy James, who's a friend of mine from North Carolina, suggested it, and I had been thinking about it anyway.

There are lots of photos in the book that have never been published before. Have you ever thought of publishing a photo book?

That's not a bad idea. Actually, the first pressing of 5,000 copies of the book is finished. We're hoping to do a reissue and probably get an American distributor or publisher. When that happens, we also plan to include some more photos.

How are things for you presently?

Things are going well. I'm out there playing and touring. I've been doing a lot of conventions. I also want to get into the studio and do some recordings. A lot of people have said I should do something like Fistful of Alice - the Cooper hits - since I'm the one who wrote much of it and played the guitar.

Let's talk about some of the songs you wrote. "Blue Turk" from School's Out was a bit of a stylistic departure at the time.

Well, there was a side to the band that was sort of beatnik or jazz-like. Dennis used to say that if he had a club, he would call it The Blue Turk. It was just one of those things we would talk about, and whenever we were in New York we would get into that beatnik, back-alley frame of mind. There were all these sides to the band. There was a psychedelic side and a hard rock side and a beatnik/blues side - and of course a comic side. "Alma Mater", "Slick Black Limousine", "Public Animal No.9".those were things we sort of picked up from The Beatles, like little skits. There were all these sides to the band, which I felt would have allowed us to go on and do a lot more recording and a lot more records. But of course Alice flew the coop.

A lot of people don't realize that, in the early days of the band, you occasionally took the vocals. On Easy Action, for instance, you sang the ballad "Beautiful Flyaway".

Oh, yeah. "Beautiful Flyaway", and on "Sing Low, Sweet Cheerio" I sing a verse, and then Alice sings a verse. At that time we were still trying to figure out who was going to be the lead singer. Alice was still Vince then, or at least we were still calling him Vince.

Let's talk about the band in its heyday. In Bob Greene's book, Billion Dollar Baby, you came across as the group's musical director.

Yeah. A lot of the book was done while we were out on the road touring. The fuel embargo was happening, and a lot of times the stage [props] wouldn't show up. Alice was doing articles and interviews, and he would talk about everything in the world except the band. I think that bothered a lot of members of the group.

No one ever seemed to confront Cooper about it.

I think a lot of that had to do with management. They tried to keep Alice isolated from the rest of the band, and I think that's what eventually led to Alice leaving. He was just in a world apart.

According to the VH-1 profile, part of the problem was also that the band was getting tired of theatrics.

That's what Alice likes to say, but that's not really the case. What happened was, we had been on the road constantly, and we just wanted to do an album that was a collection of songs, which was what Muscle of Love ended up being. That was really all there was to it. After that, we were ready to go again. As a matter of fact, when Alice walked away from the band, we had been working on the concept that later evolved into the Battle Axe album. Originally we were going to do that with Alice, but then he left, and we went ahead and did it without him. And it was a very theatrical album. I think that was just another story to tell, to make people think that he was into the theatrics, and we weren't, and that's why he left. But that's not true.

Do you think management was instrumental in his decision to drop out of the project?

Well, Shep had lost two-thirds of the publishing in a lawsuit - all the way up to Billion Dollar Babies - so he was basically faced with starting over. He started signing other people, and I think he didn't want to deal with the whole band. He just wanted to deal with Alice, and I think he figured he could make just as much money without the group. So he got Bob Ezrin and a bunch of other people who used to sit in on our albums - like [Steve] Hunter and [Dick] Wagner - and put together a band for Alice. They went in and did Nightmare, and voila! You had a Cooper band without The [Alice] Cooper Group.

If Welcome To My Nightmare had failed commercially, do you think Cooper might have come back to the original group?

I don't know. Maybe. It didn't take long after that for the albums to start failing. Nightmare was the peak, and I think a lot of that had to do with the fact that people didn't know the band was missing. On the Nightmare tour, they placed the band behind a screen, so a lot of people didn't even know The [original Alice Cooper] Group was gone until after the tour was over. Later, it became more and more evident with each album. And look where things are today - his last four albums haven't even charted. So I think a lot of that had to do with staying power. He didn't have much to draw on, and he's hired all these people to come and do things for him.

In retrospect it's clear that The Alice Cooper Group had an amazing chemistry. What do you think accounts for that?

I think when you have five people like we were, the total is more than the sum of its parts. A lot of different things went into the chemistry of the band. We had a lot of different tastes, so you got a lot of different styles of music. Plus, I think the theatrics came at a time when that was perfect for something like that to happen. And also, I think Bob Ezrin contributed a lot to the chemistry of the band. He's a great producer, and I think we worked well together. It's almost like what the Beatles had with George Martin. George Martin helped add a lot of interesting things to The Beatles' music, and I think Bob Ezrin gave us something like that as well. The combination really was magical. Unfortunately, it seems the music was never taken all that seriously. At the time, the focus was on the theatrics.

What was the songwriting dynamic like between you and Cooper? Did you occasionally come up with the music and melodies, and then he would write the lyrics?

Sometimes. But then sometimes the lyrics wouldn't get rewritten. That was true of "Be My Lover" and "Caught In A Dream" stayed pretty much like it was. On the other hand, "No More Mr. Nice Guy" changed from being about a guy and a girl to being about Alice and the press. It just depended on what the song was about to begin with. If the song fit what we were doing, we might keep the lyrics that were [originally] there. Other times, Alice would create a sort of story.

Were you happy, for the most part, with the lyrics Cooper would come up with?

Yeah, pretty much. I'm not a big lyric person, and Alice is a really clever lyricist. For the most part I think he did a good job.

From a musical standpoint, which album were you most pleased with?

Killer was a great album. We were really on the mark with that one. My manager once sat down and timed it, and he says there's three times as much music as there are vocals on the album. There's just a lot of music.

With regard to the band's history, what was it about Los Angeles that seemed unsuitable to the group, and what prompted the move to Detroit?

A lot of bands around L.A. - The Doors, The Beach Boys, Three Dog Night - were part of a different scene. They weren't really into us at the time. And also, as far as our playing ability went, we were still getting that together. When we moved to Detroit, we found that people who were much more into where we were coming from and what we were doing. It was a different scene and one where we could grow and write. It worked out really well.

At what point did the group move to the mansion in Connecticut?

We had done Love It To Death and Killer in Chicago, so it was after that. While we were in Connecticut we went onto do School's Out and Billion Dollar Babies. A lot of pre-production for School's Out and Billion Dollar Babies was done at the estate. And then we did more work on School's Out in Los Angeles, and then we recorded Billion Dollar Babies in New York and London. There was a kind of international flavor to that album.

Does Buxton appear on Muscle of Love at all?

No, Bob Dolin and Mick Mashbur were brought in to work with us on that.

Do you think the band would have broken up whether or not Buxton had had his troubles?

I don't know. I think Glen's problems were participated. Eventually Alice and Neal and I went to Glen and asked him to step down. We were still gonna let him come to rehearsals or do whatever he needed to do. We wanted him to get help, and we were still going to pay him whatever he was earning. But he refused. He was really stubborn. That caused a lot of problems, and I think it did make it easier for Alice to walk. It was easier for him to leave the whole band than it was for him to stay and add another player.

Is it fair to say that Cooper's drinking was of an entirely different nature than Buxton's?

Well, I think it alienated Alice as well. I think Alice went much more into himself. But at the time everybody just wanted some time off. That's why we did solo projects, but then that became a very convenient time for Alice to go ahead and exit and do whatever he wanted to do.

And you think Shep Gordon wanted that to happen?

I don't really think [Gordon] wanted the band to stay together. I think he could have done a lot more to keep the group intact, had he wanted that to happen. We looked to Shep for guidance. If he had wanted the band to stay together, because Alice would have done whatever Shep wanted. But I don't think Shep really cared. After doing Nightmare, they pulled out all the stops and really blew us out of the water. I imagine the thinking was that they really didn't need us anymore.

How close were you and Cooper in the early days?

Well, we worked together and we were around each other from day to day. But then we were also kind of private and had our own lives. Neal and I were good friends, and Glen and I were good friends as well. I suppose I wasn't quite as close to Alice and Dennis, but that was really just a matter of different interests and different attitudes. Looking back, I probably could have been a lot closer to Alice, but we were all busy doing whatever we were doing. It wasn't as if we never did anything together. We went to movies and so forth, but as far as being really close, Alice was closer to Glen and Dennis. Today, though, I think Alice just lives in his own world.

To return to songwriting a moment, how much of your writing was done on piano?

I wrote a lot on piano. Although I didn't play [the keyboards segue] into "Dwight Fry," on the Love It To Death album and I didn't play "Mary Ann" [from Billion Dollar Babies], I did write both those pieces. Al McMillan, a friend of Bob Ezrin who lived in Toronto, played the piano on "Mary Ann" because I'm not that accomplished as a pianist. But I grew up playing. As a matter of fact, when I was in eighth grade and getting ready to go into high school, I wrote the song "Crazy Little Child," which we later did on Muscle Of Love. I still do a lot of writing on piano.

Did you have any formal training?

I took piano lessons for a couple of years, and I took guitar lessons for a couple of years. But I was a slow reader, so I eventually stopped reading and started playing by ear.

Have there been extended periods since the group broke up where you haven't been active musically?

Well, after the band broke up I got married, and I was married till the early '90s. I got into the studio every once in a while and played piano and wrote some songs, but for the most part it was pretty low profile. I also raised three kids. And then I got divorced and remarried, but that didn't last too long. So now I'm single, and I'm pretty much concentrating on my career.

Are you enjoying life a great deal now?

Oh, yeah. The fans are great, and they seem to really enjoy the music.

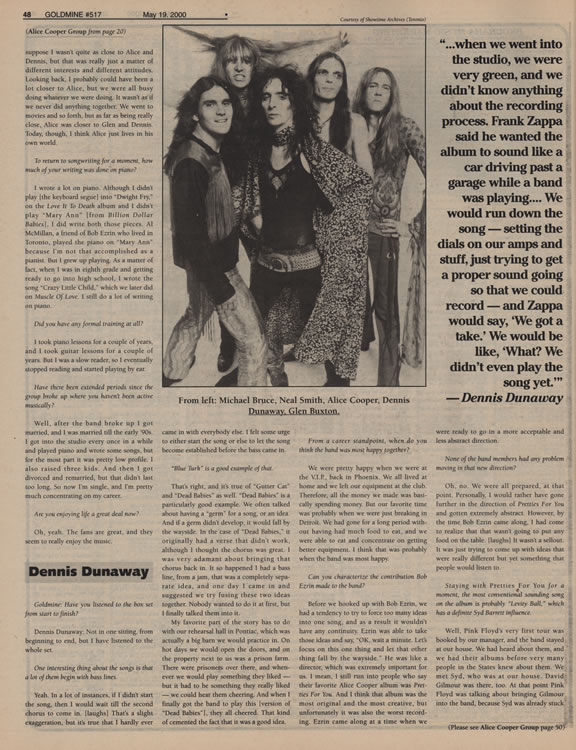

Dennis Dunaway

Have you listened to the box set from start to finish?

Not in one sitting, from beginning to end, but I have listened to the whole set.

One interesting thing about the songs is that a lot of them begin with bass lines.

Yeah. In a lot of instances, if I didn't start the song, then I would wait till the second chorus to come in. [laughs] That's a slight exaggeration, but it's true that I hardly ever came in with everybody else. I felt some urge to either start the song or else let the song become established before the bass came in.

"Blue Turk" is a good example.

That's right, and it's true of "Gutter Cat" and "Dead Babies" as well. "Dead Babies" is a particularly good example. We often talked about having a "germ" for a song, or an idea. And if a germ didn't develop, it would fall by the wayside. In the case of "Dead Babies", it originally had a verse that didn't work, although I thought the chorus was great. I was very adamant about bringing the chorus back in. It so happened I had a bass line, from a jam, that was a completely separate idea, and one day I came in and suggested we try fusing the two ideas together. Nobody wanted to do it at first, but I finally talked them into it.

My favorite part of the story has to do with our rehearsal hall in Pontiac, which was actually a big barn we would practice in. On hot days we would open the doors, and on the property next to us was a prison farm. There were prisoners over there, and whenever we would play something they liked - but it had to be something they really liked - we could hear them cheering. And when I finally got the band to play this [version of "Dead Babies"], they all cheered. Hat kind of cemented the fact that it was a good idea.

From a career standpoint, when do you think the band was most happy together?

We were pretty happy when we were at the V.I.P., back in Phoenix. We all lived at home and we left our equipment at the club. Therefore, all the money we made was basically spending money. But our favorite time was probably when we were just breaking in Detroit. We had gone for a long period without having had much food to eat, and we were able to eat and concentrate on getting better equipment. I think it was probably when the band was most happy.

Can you characterize the contribution Bob Ezrin made to the band?

Before we hooked up with Bob Ezrin, we had a tendency to try and force too many ideas into one song, and as a result it wouldn't have a continuity. Ezrin was able to take those ideas and say, "OK, wait a minute. Let's focus on this one thing and let that other thing fall by the wayside." He was like a director, which was extremely important for us. I mean, I still run into people who say their favorite Alice Cooper album was Pretties For You. And I think that album was the most original and most creative, but unfortunately it was also the worst recording. Ezrin came along at a time when we were ready to go in a more acceptable and less abstract direction.

None of the band members had any problem moving in that new direction?

Oh, no. We were all prepared at that point. Personally, I would rather have gone further in the direction of Pretties For You and gotten extremely abstract. However, by the time Bob Ezrin came along, I had come to realize that that wasn't going to put any food on the table. [laughs] It wasn't a sellout. It was just really trying to come up with ideas that were really different but yet something that people would listen to.

Staying with Pretties For You for a moment, the most conventional sounding song on the album is probably "Levity Ball," which definitely has a Syd Barrett influence.

Well, Pink Floyd's very first tour was booked by our manager, and the band stayed at our house. We had heard about them, and we had their albums before very many people in the States knew about them. We met Syd, who was at our house. David Gilmour was there, too. At that point Pink Floyd was talking about bringing Gilmour into the band, because Syd was already stuck in outer space, unfortunately. They sounded great, though. We saw them do a show at the Cheetah Club, where they performed the songs from their first American album, Piper At the Gates of Dawn. It was incredible.

But you're right: "Levity Ball" has that same melody line as "Astronomy Domine." At the time, I didn't realize it was the same, because "Astronomy Domine" wasn't on Pink Floyd's first American album. It was only on the British release. Still, I'm sure someone in our band had heard it and was influenced by it, because it's just too close.

Which of The Alice Cooper Group's albums do you like best?

That's a difficult question. I like Pretties For You for its originality. When you create music that sounds like other music going on at the time, it becomes dated. On the other hand, when you do something different, it has a better chance of holding up over time. Unfortunately, when we went into the studio, we were very green, and we didn't know anything about the recording process. Frank Zappa said he wanted the album to sound like a car driving past a garage while a band was playing. That was his goal, and I think he more or less achieved it. He had us set up our own amps around the drum set, so there was total leakage. We would run down the song - setting the dials on our amps and stuff, just trying to get a proper sound going so we could record - and Zappa would say, "We got a take." We would be like, "What? We didn't even play the song yet." But as far as favorite albums go, I would also say I like Killer and Love It To Death, which were recorded at RCA Studios in Chicago. I thought those albums had the best sound, and that studio was the reason.

A lot of high-profile artists - Harry Nilson, Marc Bolan, and others - were present at that sessions for Billion Dollar Babies. Did any of those people play on the album?

I think Donovan was the only one. It's too bad we didn't get more. It would have been great to have backing vocals from Flo And Eddie, but I don't think they're on there. And Harry Nilson had an incredible voice. It's just unfortunate that it was uncontrollable because he was drinking so much. You couldn't get anything done when he was around. He would just fall across the mixing board and knock all the faders out of whack. But then he would stumble out into the studio and sit down at the piano, and his voice and what he was playing would sound incredible. I was like, "I can't believe this guy. Why doesn't he just stay there and play and sing for the rest of his life?"

Keith Moon was the same way. Moon was hilarious, but when he sat at the drums he couldn't even stay on the stool. So we didn't miss anything by not having Moon on the album. Rick Gretch was also there. He played bass on a jam, which I'm pretty sure was recorded, by the way. But we worked so quickly that we hardly ever did extra takes. By the time we went into the studio, we usually even knew what the song order would be.

Everyone seems to have his own take on the breakup of the band.

Well, one thing that contributed to the breakup, I think, is that there were new people being hired, and those people who supposedly worked for the band became very protective of Alice. It got to the point where it was almost like we had to call Alice to get permission to go over to his room. Otherwise, these guys wouldn't let us in. Of course the band members resented that. That sort of thing grated on everybody, especially when we were touring for so long, even when we were sick. At one point I even went on tour in a wheelchair. We were just at the breaking point. We might go to do an interview, and the people who supposedly worked for the band would shove us out of the way, so that Alice could walk through. That was totally unnecessary.

One would presume Cooper himself could have done something about that situation.

We thought so, but it didn't happen that way.

Is it true that the Battle Axe album was originally intended to be an Alice Cooper album?

Yes. We extended an invitation to Alice, for what we felt was the album we had planned to do after we took some time off. But by then we couldn't really talk to Alice. People would screen our calls and tell us that they would get the message to Alice. At that point, even though we owned the name "Alice Cooper" - we had signed papers indicating that we owned the name - we decided not to hire the lawyers. We wanted to keep the door open, so in good faith we spent our own money to do the album, hoping that we could come back together as planned. And by the way, that was a very theatrical album.

Once it was apparent that Cooper was gone, did you and the remaining members ever discuss recruiting a replacement for him?

You mean somebody who would imitate Alice? [laughs] We thought Alice was going to come back, for the Billion Dollar Babies [Battle Axe] project. We couldn't believe it was going down the way it was. Alice is a good guy, and I consider him my best friend. We were in denial, in that way. As far as not being on stage and not touring, that doesn't bother me as much as the fact that somebody who I thought was my best friend could just sort of eliminate me and eliminate everything that I had worked for creatively, overnight.

It says something that all of you - even Cooper - have kept in touch with one another through the years.

Well, obviously, Neal and I are close. We get together and play a lot. For the past several years we've played better than we did when the band was together, as far as technical things go. It helps a lot when it's just a bass and drums, because you can really cue in on one another. Neal and I don't even have to look at each other to know what each of us is going to do, when we're just jamming. And then Glen lived nearby for many years, before he moved back to Phoenix and then to Iowa. After that I would talk to him on the phone but not that often. And Mike Bruce keeps in touch. He talks to Neal more often than he talks to me, but I think that's because he knows Neal will pass on whatever he says. We communicate that way.

What was the show that occurred just before Buxton died?

Neal and Mike went to a convention in Texas, and they invited Glen to come out. Unfortunately, my health was such that I wasn't able to do it, although I really would have loved to. Glen was thrilled. He had such a good time, and then when he went back to Iowa, he was all excited because they were planning to do it again. It was really an "up" point in his life. But while he was there in Texas, he was complaining that he had a pain in his chest. Neal kept telling him he should go see a doctor, but Glen wouldn't do it. Unfortunately when he finally did go, it was too late. The problem had turned into pneumonia.

How would you characterize Buxton's contribution to the band?

Well, Glen taught me how to play bass, way back when we were in high school. He was the first member of the band who knew how to play an instrument. Besides the total abstractness of his playing, I think Glen's image was extremely important to the band. Glen's attitude sort of drove the soul of the band. 24 hours a day. I remember when I would go over to Glen's house in high school in the afternoon. I would open the door to his room and have to step in certain places, because the floor would be completely covered with his guitar and music books, and so forth. And for the entire time I knew him, his room - even if he had just checked into a hotel room - would be completely covered like that within five minutes. Another thing I like about Glen is that he always left the price tag on everything he bought. There were a million things like that. It's hard to describe him in all his glory.

What do you think accounted for the magic of the original band?

I think we all had a burning desire to create, and we all felt very strongly about our ideas. Whenever we would be together in a room, whether it was alone or in a restaurant full of people, we would always be talking about music. To someone who didn't know us, it sounded like we were arguing because we all believed so much in our ideas. And we would fight for our ideas, but when it came to solidify things, we would choose, then bow out and go with what was best. Instead of "magic," I think it was more a matter of hard work and a relentless burning desire. We compensated for not being able to play like Jack Bruce, or someone technical, by working on music all the time. We would rehearse for 10 hours a day, and when we weren't rehearsing, we were thinking of ideas for the band. It was a 24-hour-a-day thing.

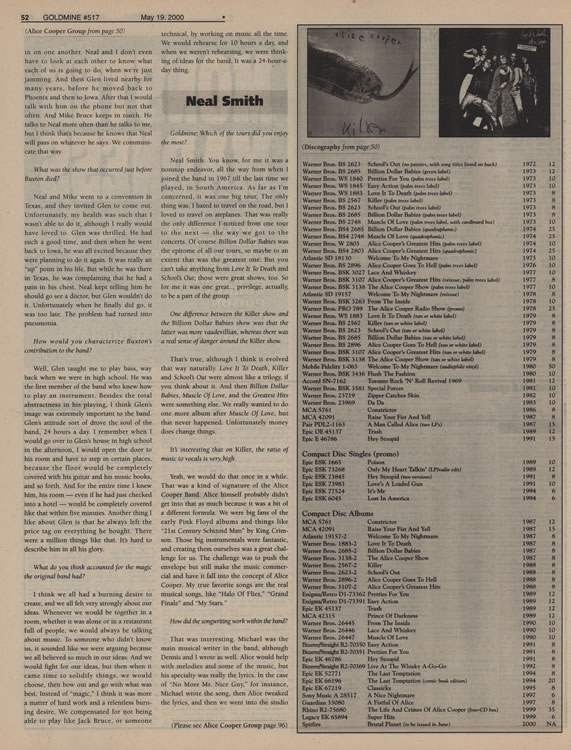

Neal Smith

Which of the tours did you enjoy the most?

You know, for me it was a nonstop endeavor, all the way from when I joined the band in 1967 till the last time we played, in South America. As far as I'm concerned, it was one big tour. The only thing was, I hated to travel on the road, but I love to travel on airplanes. That was really the only difference I noticed from one tour to the next - the way we got to the concerts. Of course Billion Dollar Babies was the epitome of all our tours, so maybe to an extent that was the greatest one. But you can't take anything from Love It To Death and School's Out; those were great shows, too. So for me it was one great. privilege, actually, to be part of the group.

One difference between the Killer show and the Billion Dollar Babies show was that the later was more vaudevillian, whereas there was a real sense of danger around the Killer show.

That's true, although I think it evolved that way naturally. Love It To Death, Killer and School's Out were almost like a trilogy, if you think about it. And then Billion Dollar Babies, Muscle Of Love, and the Greatest Hits were something else. We really wanted to do one more after Muscle Of Love, but that never happened. Unfortunately, money does change things.

It's interesting that on Killer, the ratio of music to vocals is very high.

Yeah, we would do that once in a while. That was a kind of signature of the Alice Cooper Band. Alice himself probably didn't get into that as much because it was a bit of a different formula. We were big fans of the early Pink Floyd albums and things like "21st Century Schizoid Man" by King Crimson. Those big instrumentals were fantastic, and creating them ourselves was a great challenge for us. The challenge was to push the envelope but still make the music commercial and have it fall into the concept of Alice Cooper. My true favorite songs are the real musical songs, like "Halo Of Flies", "Grand Finale" and "My Stars".

How did the songwriting within the band work?

That was interesting. Michael was the main musical writer in the band, although Dennis and I wrote as well. Alice would help with melodies and some of the music, but his specialty was really the lyrics. In the case of "No More Mr. Nice Guy" for instance, Michael wrote the song, then Alice tweaked the lyrics, and then we went into the studio and arranged it with Bob Ezrin.

But it worked other ways, too. "Hallowed Be My Name" ended up pretty much like I wrote it. And then a song like "Alma Mater", was one of the last songs on School's Out, or "Unfinished Sweet", off Billion Dollar Babies. Those had quite a few arrangements changed by Bob Ezrin. Everyone in the band helped arrange songs. I would typically go to Michael with a song, because I'm not a guitar player. The little bit of guitar playing and keyboard work I've done over the years has come from teaching myself or having Mike teach me chords. So I would tend to write, then work on the melodies with someone who's an expert, like Mike. And Dennis writes, too. "Black Juju" was originally his idea. In the case of "School's Out", everybody had a hand in writing that song. That was a perfect example of total collaboration among the band.

Have you ever heard a drummer other than yourself play the drum part for "Billion Dollar Babies" properly?

No, not even close. Bob didn't want me to play that [mimics the intro to the song]. That required a big fight, to get that drum part on there, and now it's one of the most famous drum parts in rock 'n' roll. But I was very serious about getting it on there. Bob said, "If you're going to play that, you're going to play it perfect." And I said, "Fine, I'll play it perfect." And we eventually did get the perfect take for it. But that's just one example of the types of things you run into. And I have empathy for Bob. If I were producing, I'd probably say the same thing. He really wanted a straighter feel.

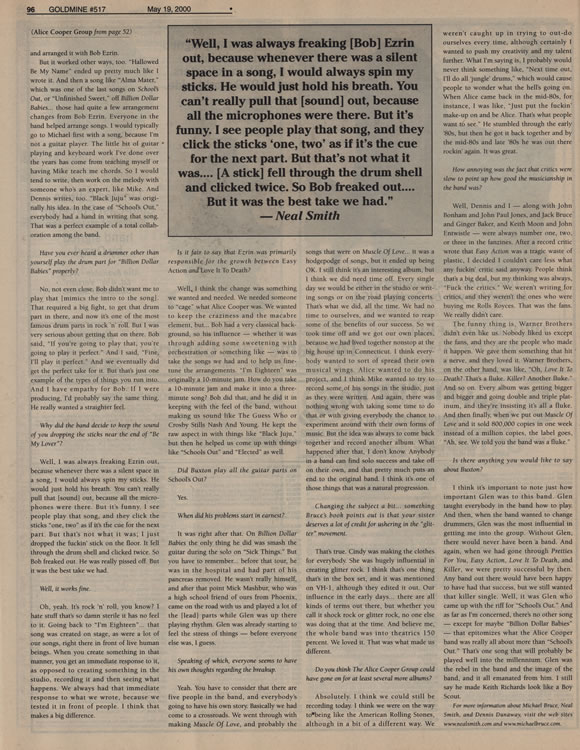

Why did the band decide to keep the sound of you dropping the sticks near the end of "Be My Lover"?

Well, I was always freaking Ezrin out, because whenever there was a silent space in a song, I would always spin my sticks. He would just hold his breath. You can't really pull that [sound] out, because all the microphones are there. But it's funny. I see people play that song, and they click the sticks "one, two" as if it's the cue for the next part. But that's not what it was; I just dropped the fuckin' sticks on the floor. It fell through the drum shell and clicked twice. So Bob freaked out. He was really pissed off. But it was the best take we had.

Well, it works fine.

Oh, yeah. It's rock 'n' roll, you know? I hate stuff that's so damn sterile it has no feel to it. Going back to "I'm Eighteen"..that song was created on stage, as were a lot of our songs, right there in front of live human beings. When you create something in that manner, you get an immediate response to it, as opposed to creating something in the studio, recording it and then seeing what happens. We always had that immediate response to what we wrote, because we tested it in front of people. I think that makes a big difference.

Is it fair to say that Ezrin was primarily responsible for the growth between Easy Action and Love It To Death?

Well, think the changes was something we wanted and needed. We needed someone to "cage" what Alice Cooper was. We wanted to keep the craziness and the macabre element, but. Bob had a very classical background, so his influence - whether it was through adding some sweetening with orchestration or something like that - was to take the songs we had and to help us fine-tune the arrangements. "I'm Eighteen" was originally a 10-minute jam. How do you take a 10-minute jam and make it into a three-minute song? Bob did that, and he did it in keeping with the feel of the band, without making us sound like The Guess Who or Crosby Stills Nash and Young. He kept the raw aspect I n with things like "Black Juju", but then he helped us come up with things like "School's Out" and "Elected" as well.

Did Buxton play all the guitar parts on School's Out?

Yes

When did his problems start in earnest?

It was right after that. On Billion Dollar Babies the only thing he did was smash the guitar during the solo on "Sick Things". But you have to remember.. before the tour, he was in hospital and had part of his pancreas removed. He wasn't really himself, and after that point Mick Mashbur, who was a high school friend of ours from Phoenix, came on the road with us and played a lot of the [lead] parts while Glen was up there playing rhythm. Glen was already starting to feel the stress of things - before everyone else was, I guess.

Speaking of which, everyone seems to have his own thoughts regarding the breakup.

Yeah. You have to consider that there are five people in the band, and everybody's going to have his own story. Basically we had come to a crossroads. We went through with making Muscle Of Love, and probably the songs that were on Muscle Of Love. It was a hodgepodge of songs, but it ended up being OK. I still think it's an interesting album, but I think we did need time off. Every single day we would either be in the studio or writing songs or on the road playing concerts. That's what we did, all the time. We had no time to ourselves, and we wanted to reap some of the benefits of our success. So we took time off and we got our own places, because we had lived together nonstop at the big house up in Connecticut. I think everybody wanted to sort of spread their own musical wings. Alice wanted to do his project, and I think Mike wanted to record some of his songs in the studio, just as they were written. And again, there was nothing wrong with taking some time to do that or with giving everybody the chance to experiment around with their own forms of music. But the idea was to come back and record another album. What happened after that, I don't know. Anybody in the band can find solo success and take off on their own, and that pretty much puts an end to the original band. I think it's one of those things that was a natural progression.

Changing the subject a bit.something Bruce's book points out is that your sister deserves a lot of credit for ushering in the "glitter" movement.

That's true. Cindy was making clothes for everybody. She was hugely influential in creating glitter rock. I think that's one thing that's in the box set, and it was mentioned on VH-1, although they edited it out. Our influence in the early days.there are all kinds of terms out there, but whether you call it shock rock or glitter rock, no one else was doing that at the time. And believe me, the whole band was into the theatrics 150 percent. We loved it. That was what made us different.

Do you think that The Alice Cooper Group could have gone on for several more albums?

Absolutely. I think we could still be recording today. I think we were on the way to being like the American Rolling Stones, although in a bit of a different way. We weren't caught up in trying to out-do ourselves every time, although I certainly wanted to push my creativity and my talent further. What I'm saying is, I probably would never think something like, "Next time out, I'll do all 'jungle' drums," which would cause people to wonder what the hell's going on. When Alice came back in the mid-80s, for instance, I was like, "Just put the fucking make-up on and be Alice. That's what people want to see." He stumbled through the early '80s, but then he got it back together and by the mid-80s and late '80s he was out there rockin' again. It was great.

How annoying was the fact that critics were slow in pointing up how good the musicianship in the band was?

Well, Dennis and I - along with John Bonham and John Paul Jones, and Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, and Keith Moon and John Entwistle - were always number one, two or three in the fanzines. After a record critic wrote that Easy Action was a tragic waste of plastic, I decided I couldn't care less what any fuckin' critic said anyways. People think that's a big deal, but my thinking was always, "Fuck the critics." We weren't writing for critics, and they weren't the ones who were buying me Rolls Royces. That was the fans. We really didn't care.

The funny thing is, Warner Brothers didn't even like us. Nobody liked us except the fans, and they are people who made it happen. We gave them something that hit a nerve, and they loved it. Warner Brothers on the other hand, was like, "Oh, Love It To Death? That's a fluke. Killer? Another fluke." And so on. Every album was getting bigger and bigger and going double and triple platinum, and they're insisting it's all a fluke. And then finally, when we put out Muscle Of Love and it sold 800,000 copies in one week instead of a million copies, the label goes, "Ah, see. We told you the band was a fluke."

Is there anything you would like to say about Buxton?

I think it's important to note how important Glen was to this band.

Glen taught everybody in the band how to play. And then, when the band wanted to change drummers, Glen was the most influential in getting me in the group. Without Glen, there would never have been a band. And again, when we had gone through Pretties For You, Easy Action, Love It To Death and Killer, we were pretty successful by then. Any band out there would have been happy to have had that success, but we still wanted that killer single. Well, it was Glen who came up with the riff for "School's Out". And as far as I'm concerned, there's no other song - except for maybe "Billion Dollar Babies" - that epitomizes what the Alice Cooper band was really all about more than "School's out". That's one song that will probably be played well into the millennium. Glen was the rebel in the band and the image of the band, and it all emanated him. I still say he made Keith Richards look like a Boy Scout.